Abstract

As pollinators, bees provide an essential ecosystem service that supports biodiversity and agriculture. To be successful pollinators, bees need to adjust their activities to the times when the plants offer pollen and nectar. The bees do so by coupling their inner biological clocks not only to environmental cycles, like seasons, but also to the inner clocks of plants. But how do bees “tell time” so that they can organize their activities? To answer this question, we developed an easy-to-use and low-cost monitoring device to track the activity of different species of social bees throughout the day. With our device, we could do more than describe bees’ activity patterns—we also found that bees are active during the night. Altogether, our results help us to understand the activity schedules of these essential pollinator and how they may be affected by environmental factors in the face of climate change and human activities.

How do Animals “Plan” and “Tell Time”?

Did you ever wonder how animals track time without a clock? Guess what? Animals have super-cool clocks, too! These clocks are just a little bit different from the clocks you are probably thinking of. In fact, most living beings rely on an inner biological clock to organize their daily activities and behaviors. This includes you! But why are biological clocks important?

The biological clocks of insects and other organisms allow them to predict normal daily changes in Earth’s environmental conditions, including changes in temperature, humidity, light, and food availability [1]. The biological clock is also involved in the control of the body’s internal cycles. Have you ever noticed how you generally fall asleep or feel hungry always at the same times of the day, every day? These are examples of how the biological clock works. More interestingly, this clock also ticks with a duration of around 24 h. That is why it is called the “circadian” clock—from the Latin circa, which means “around”, and dian, which means “day”.

Social bees are very interesting organisms in which to study biological timing, as some species are grouped in well-organized societies, just like us. Some bee species may live in hives that house hundreds or even thousands of individuals. These societies are composed of a single queen that lays eggs, and female workers that perform all the other tasks. Such bees are called highly eusocial bees [2]. The activities of these bees depend on both internal (individual and social) conditions and external environmental conditions like light and temperature.

For example, in honeybees, there are two main tasks performed by the workers. The first task is performed by the young bees, nurses, which care for and feed the larvae. The older bees are responsible for gathering resources including pollen, nectar, and water, which is called foraging. Interestingly, these two types of workers differ in their circadian rhythms. Nurses work around the clock, as their sisters, while still larvae need their constant attention. Foragers are very well synchronized with the daily cycle, meaning they have fixed periods of sleep and activity.

How Can We Monitor the Daily Activities of Bees?

Traditionally, the movements of an individual organism are recorded to understand how its internal clock works. Movement studies can also be used to understand how an organism “syncs up” with external signals, like light for example. However, this method does not work well for bees. As social insects, bees need to be in contact with their nestmates [3]. So how can we monitor the activity rhythms in a natural colony, such as foraging behavior?

The simplest way to monitor the activity of a hive is by counting the number of times bees go in and out of the hive. The problem is that this method requires several hours of work, and it is easy to lose count. To solve this problem, we developed a low-cost, electronic device to automatically monitor hive activity.

How Does Our Electronic Monitoring Device Operate?

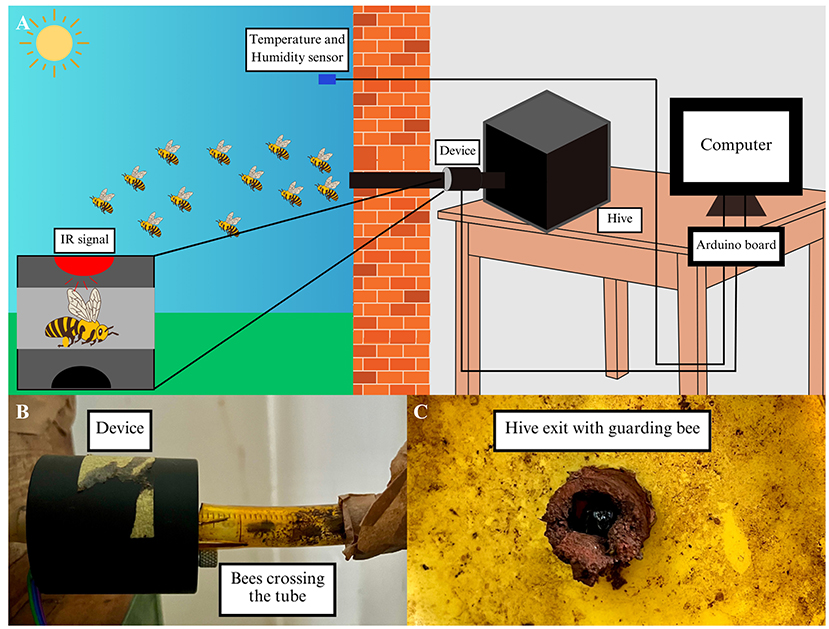

Our hive-monitoring device consists of an infrared (IR) sensor, which counts the bees that cross through the IR beam. Like us, bees do not see infrared light, so it does not bother or affect them. The numbers of crossings are added up over a defined time interval (Figure 1). What is really cool is that the counting can be done over several days, and our device is automatic and very easy to use. Researchers only need to place a glass tube (the diameter of which can be adjusted according to the bees’ size) into the entrance of the hive and connect the device to a computer (Figure 1).

- Figure 1 - (A) Experimental setup developed for monitoring the activity of colonies of eusocial bees (image generated using https://canva.com).

- (B) A glass tube is placed into the hive entrance, and the bees are counted by our infrared sensor device as they pass through the tube. (C) A close-up of the exit tube of the device, in the hive of an experimental colony of stingless bees.

The recording is based on Arduino, which is a simple, open-source platform that is easy to program. You can learn more about Arduino here. In the setup shown in Figure 1, we kept the colonies in an observation room, but this setup could also work in outdoor, real-world conditions.

Every Species Has Its Own Preferred Timing of Foraging

Several questions may arise when studying how animals, like bees, behave. For example, does their body size affect when they work? Or could bees also have a favorite time to be active, just like us? Some people, for example, are early birds (they wake up early), while others are night owls (they stay up late).

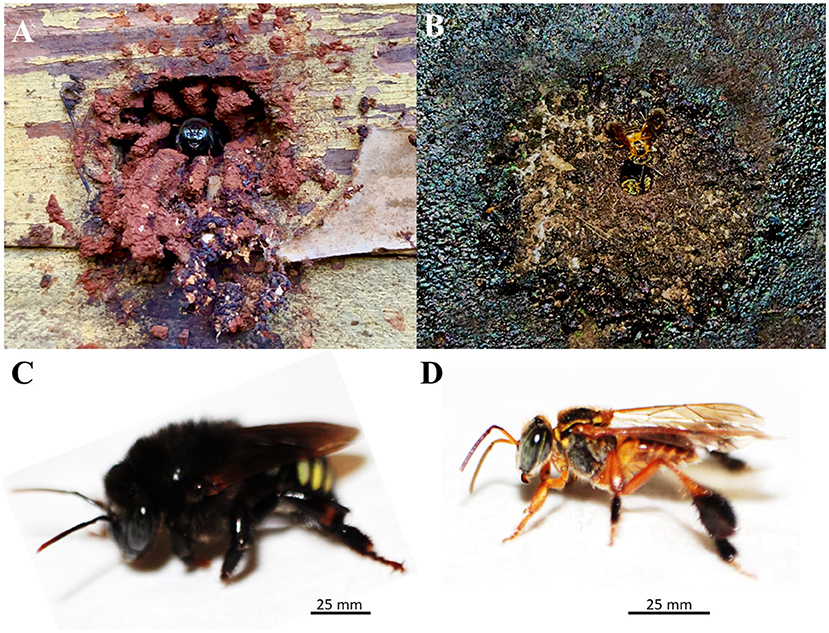

To address these two questions, we monitored three different species of social bees. The first one was the honeybee, which is found worldwide, and two species of stingless bees. The first stingless species was the mandaçaia bee (meaning “wonderful guard” in Tupi-Guarani, an indigenous language from Brazil), a large, black, hairy species. The second stingless species was the rather slender and much smaller yellow marmelada bee. Neither species can sting, and they are native to South America, mainly Brazil (Figure 2).

- Figure 2 - The stingless bee species analyzed in our study.

- (A) Mandaçaia bee guarding the nest entrance. (B) Yellow marmelada bee workers at the entrance of a hive. (C, D) Images of a mandaçaia and a yellow marmelada bee, respectively. The black bars below the images indicate the size scale of the bees.

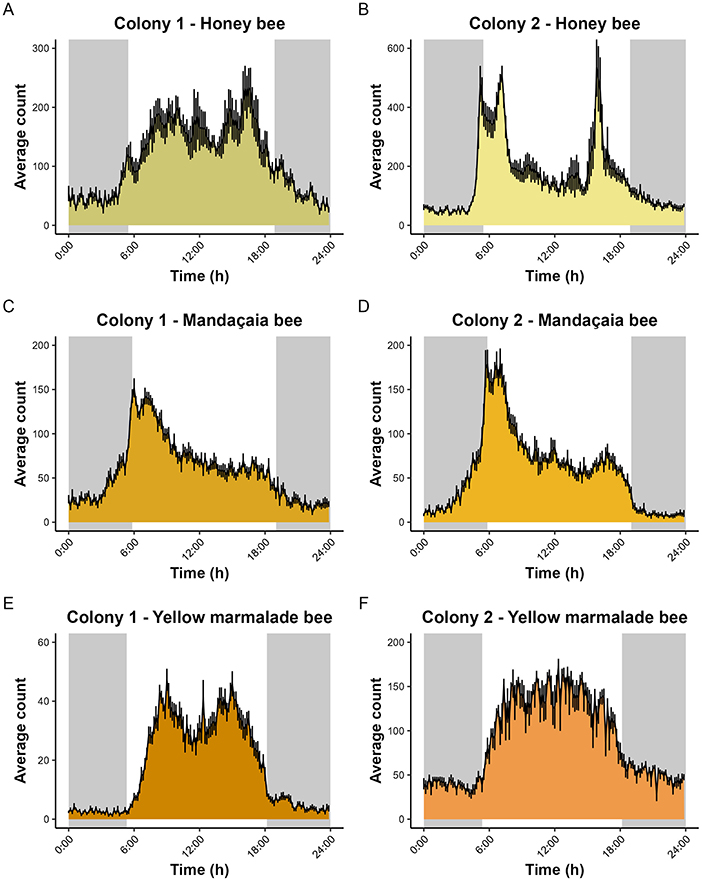

We analyzed the averaged daily in-and-out counts, over a 10-day monitoring period. For each species, we simultaneously analyzed two hives (Figure 3).

- Figure 3 - Average activity of the bee colonies monitored in our 10-day experiments.

- (A, B) The two honeybee colonies had different activity patterns, with Colony 1 being constantly active during the day, and Colony 2 concentrating their outside activities in the morning and evening. (C, D) Mandaçaia bees were preferably “early birds”, with higher activity in the morning. (E, F) The yellow marmelada colonies had well-distributed activity throughout the day, with preference for warmer times. The white and gray background represents the average light-dark phases. Time is shown on the x-axis and the number of bees counted is shown on the y-axis.

For the honeybee, we found clear differences in the pattern of activity between the two hives. The activity of Colony 1 was well distributed throughout the day. In contrast, Colony 2 had two clear peaks in activity, the first in the early morning and the second in the late afternoon. This was a very cool finding, since the honeybee hives shared the same space. These results show that internal factors may influence the bees’ activity, such as their genetic backgrounds.

In contrast, the stingless bee species had more uniform and similar activity patterns between hives. The mandaçaia colonies were predominantly “early birds” and also showed increased activity during the nighttime. In contrast, yellow marmelada bee colonies had a well-distributed activity pattern throughout the whole day, but little activity during the night.

In general, these differences show that each species has preferences in their patterns of activity. But why? One big difference between these species is their size. Larger, darker species like mandaçaia can overheat in the hot tropical sun. Meanwhile, smaller, lighter species like the yellow marmelada bee may get too cold during cooler parts of the day. Because of this, both species should stay active at times that help them avoid the dangers of the weather.

Also, just like us, bees have preferred foods. Therefore, they also need to know when flowers have the most nectar or pollen available. To do this, bees match their inner clocks to the inner clocks of the plants they will visit [4]. So, it is not only animals that keep track of time—plants do, too! The sunflower is a great example—it moves its ‘head’ to follow the sun as the sun travels across the sky during the day.

Another eye-catching result is that all the colonies showed some level of activity during the night. This suggests that bees also perform tasks in the dark. Such tasks could include keeping the colony’s temperature and humidity stable, guarding the nest entrance, and removing waste from the hive—all types of activity that do not directly rely on light.

Why is it Important to Understand Insect Behavior?

As Earth’s climate changes and biodiversity is lost, pollinators are struggling to maintain their usual activities—putting both agriculture and entire ecosystems at risk. Thus, it is essential to understand how these very important insects behave. Currently, scientists all over the world are trying to comprehend how chemicals, such as pesticides, can impact non-pest species including bees, butterflies, and moths [5]. To understand the effects of chemicals like pesticides, scientists must first understand how these insects function and behave in normal conditions. Several studies have already shown that pesticides can impact insects’ daily activity patterns and learning capacity.

In conclusion, we believe a device like the one we developed and tested could be useful for studying how these potentially harmful factors influence social insects on a larger scale. Our method could also provide important information about insect health, foraging preferences, and social organization. Altogether, our results help us to understand the activity schedules of these essential pollinators and how they may be affected by environmental factors in the face of climate change and human activities.

Glossary

Biological Clock: ↑ A function of living organisms that allows them to predict and adapt to daily (~24 h) and seasonal changes in Earth’s climate.

Circadian: ↑ From Latin circa, which means “around”, and dian, which means “day”, a circadian clock is another name for the biological clock.

Eusocial: ↑ Refers to group-living species in which one dominant member has kids, and most other members of the group help raise them instead of having their own.

Larvae: ↑ The young, immature stages of many insects and other animals. Larvae hatch from eggs and spend this stage eating and growing before changing into adults.

Foraging: ↑ The action of actively searching for food or other resources. In social bees, foraging involves gathering essential resources for the colony.

Infrared Sensor: ↑ A device that detects heat or invisible infrared light, helping a machine “see” warm objects, like bees.

Stingless Bees: ↑ Highly social bees, like honeybees. They include many different species and live in warm regions around the world, including Central and South America, Africa, India and Southeast Asia, and Oceania.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. Eduardo Brandt de Oliveira (University of São Paulo, Brazil) for his assistance with the Arduino technology, and Dr. Katharina Beer (University of Würzburg, Germany) for helpful suggestions on data analysis. We also thank Anderson Roberto de Souza and the staff of the Precision Manufacturing Workshop of the USP-Ribeirão Preto campus for the design and manufacturing of the registration device. Jairo de Souza and Luis Roberto Aguiar provided assistance in maintaining the stingless bee and honey bee colonies. Luan Mazzeo provided the pictures of individual stingless bees. Financial support was granted from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, process 302209/2022-0) and scholarships to the AR by CNPq (PIBIC) and the Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP, Process 2020/05723-0 and fellowship 2022/05723-0). We also would like to thank Joaquín for the review of our manuscript. Joaquín is a 17-year old guitarist with a passion for music, math, science, and philosophy, with a new growing passion for neuroscience.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Original Source Article

↑Justino, A. R., and Hartfelder, K. 2024. A versatile recording device for the analysis of continuous daily external activity in colonies of highly eusocial bees. J. Comp. Physiol. A 210:885–900. doi: 10.1007/s00359-024-01709-2

References

[1] ↑ Saunders, D. S. 2002. Insect Clocks. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

[2] ↑ Michener, C. D. 2007. The Bees of the World, 2nd Edn. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

[3] ↑ Beer, K., Steffan-Dewenter, I., Härtel, S., and Helfrich-Förster, C. 2016. A new device for monitoring individual activity rhythms of honey bees reveals critical effects of the social environment on behavior. J. Comp. Physiol. A – Neuroethol. Sens. Neural. Behav. Physiol. 202:555–65. doi: 10.1007/s00359-016-1103-2

[4] ↑ Bloch, G., Bar-Shai, N., Cytter, Y., and Green, R. 2017. Time is honey: circadian clocks of bees and flowers and how their interactions may influence ecological communities. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. – Biol. Sci. 372:20160256. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0256

[5] ↑ Farder-Gomes, C. F., Grella, T. C., Malaspina, O., and Nocelli, R. F. C. 2024. Exposure to sublethal concentrations of imidacloprid, pyraclostrobin, and glyphosate harm the behavior and fat body cells of the stingless bee Scaptotrigona postica. Sci. Total Environ. 907:168072. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168072