Abstract

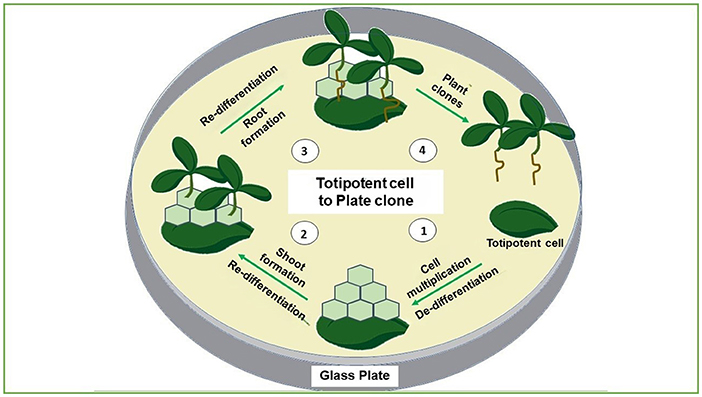

We are all familiar with plants growing from seeds placed in soil. However, some plants, such as roses, develop from stem cuttings, while other plants, like potatoes, grow from tuber (the part we eat) sprouts. But is there another way to multiply plants without seeds? The answer is yes! Starting from a piece of live plant tissue, exact copies, or clones, can be produced by providing the tissue with all the nutrients required for its growth and development. This technique, called plant tissue culture, is typically done by placing the plant tissue in a glass dish kept in a safe laboratory environment. Plant tissue culture is a fairly new way to multiply chosen plants in large numbers. In this article, you will learn why scientists choose to produce plant clones and how those clones are produced in the laboratory.

What are Plant Clones?

Plants are amazingly flexible in how they can be grown. While you might automatically think about planting seeds in soil, there is actually another cool method that does not involve seeds at all. New plants can be grown from parts of other plants, like the stems of roses or the tubers (the part we eat) of potatoes.

Even more exciting, scientists can create hundreds of identical copies from just one “mother plant”! How? By taking a tiny piece of the growing tissue and placing it in glass dishes or jars in a special lab where things are kept nice and clean, free from harmful bacteria or fungi. These identical plants are called plant clones (Figure 1). The process of making plant clones is known as plant tissue culture [1]. The process is also called micropropagation, since it only takes a small (micro) piece of plant tissue to grow a whole new plant. This amazing technique opens up many possibilities for gardening, farming, and plant science!

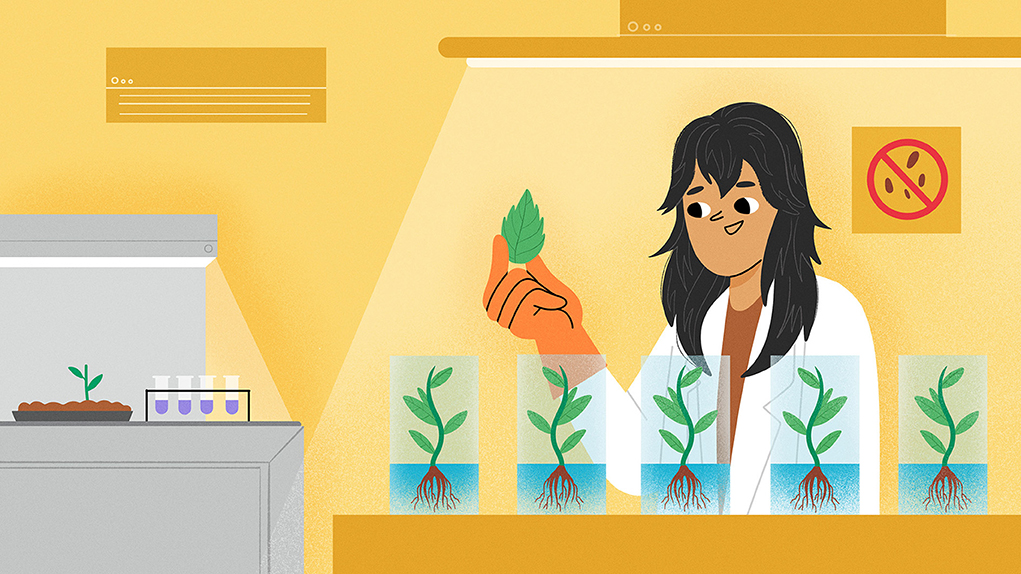

- Figure 1 - How new plants develop.

- (A) Usually, plants develop from seeds planted in soil. (B) A new plant-development method uses a small piece from a “mother plant”, grown in a nutrient-rich liquid in the lab, to create plant clones identical to the mother plant.

All living organisms, including humans, plants, and animals, develop from a single cell. To grow and mature into a complete individual with various organs, this initial cell divides repeatedly, doubling to two, then four, then eight, and so on, through a process called mitosis. Once enough cells are produced, they group together to form tissues, which then organize into organs that perform specific functions in the fully developed organism, like your lungs and heart. This process of multiplication and development is quite similar in both plants and animals. The capacity of those initial cells to divide, multiply, and develop into a complete organism is called totipotency.

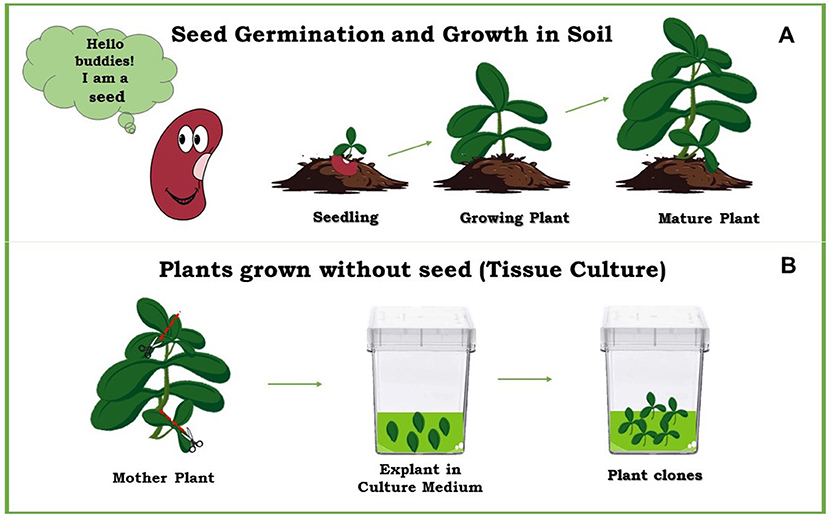

Once a plant is fully grown, it begins to produce flowers and develop seeds for the next generation. While most plant parts (other than seeds) do not typically give rise to new plants, scientists have developed a specialized nutrient mixture, which has enabled new plants to be developed from any other part of the plant. This concept, where cells can be taken from any mature part of a plant and cultured in the lab, was first introduced in the early 1900s [2]. The small plant parts taken from mature plants, such as pieces of leaves, are called explants (meaning “outside the plant”). The cells in the explant tissue undergo a process called dedifferentiation, during which the cells lose the specialized functions of the tissue they came from and return to an earlier stage when they are just dividing. After a certain number of new cells are produced, the cells then reorganize into tissues. In a process called shooting, they form structures like leaves and stems, and eventually develop roots (Figure 2). Unlike seeds, which hold saved-up nutrients for new sprouts, micropropagation depends on the addition of a nutrient-rich liquid (called medium) that promotes cell division, differentiation, and organ development.

- Figure 2 - Growing a plant clone has four main steps.

- (1) The totipotent cells from the mother plant are placed in a glass dish with nutrient-containing media. The cells dedifferentiate, which means they lose their special functions and begin dividing. (2) After few weeks, the cells redifferentiate and shoots form. (3) Next, roots form. (4) Eventually, complete plant clones are produced.

Why Choose Micropropagation?

Imagine you have a favorite plant in your garden with unique, attractive flowers. You want to collect seeds for planting next season, but the plant is not producing any seeds. In nature, certain plant species rely on bees, other insects, and birds to help seeds develop. However, if these natural helpers are absent, the plants may die without leaving any seeds behind. To grow your beloved plant, you have a few options. You could try growing new plants from its stem cuttings or suckers (new shoots developing at the base of a plant or its root). You could seek advice from a nearby commercial plant nursery for expert guidance. If these methods do not work, your last option is to approach a commercial tissue culture laboratory that performs micropropagation.

For economically important plants like medicinal species, sugarcane, turmeric, and ginger, which are grown in many places, micropropagation is an effective method for multiplication. Micropropagation greatly reduces the time and cost of producing new plants. The best plant or a storage organ such as a rhizome, (a type of plant stem that typically grows horizontally underground in plants like ginger and turmeric) is selected as the mother plant, and a portion of its tissue is micro propagated. The resulting plants will be exact copies of each other and of the mother plant. For certain economically valuable species such as bananas, potatoes, bamboo, and orchids, developing plants from seeds can be particularly challenging. Therefore, these species are more easily multiplied through micropropagation.

Plant infection can also lead to loss of seeds. For example, when plants are attacked by viruses, they cannot be saved with chemical pesticides. If vegetative parts, such as potato tubers from infected mother plants, are used for propagation, the virus will transfer to the new plants. In such situations, healthy plants can be produced using disease-free growing tip cells from a mother plant that has not been infected by the virus.

Sometimes, growers want to strengthen plants by giving them desirable traits such as heat tolerance, salt tolerance, or disease resistance. We often need to select the tolerant plants among various plants by exposing them to stress condition and collect their seeds for next sowing. For example, cauliflower plants grow better in cooler temperatures, making them well-suited for winter seasons in tropical areas where they can bloom and produce seeds. But what if we want to grow them during the summer season to sell as food? In this case, we need cauliflower varieties that can thrive in the high temperatures. During selection for heat-tolerant cauliflower plants that produce the marketable edible part called curd, we face the problem in getting their seeds since flowering and seed setting requires cooler temperature. At this stage, tissue culture techniques can be used to cultivate such heat tolerant plants from the curd as explants, through micro propagation [3].

What Materials are Required for Micropropagation?

You might be curious about the materials and experimental setup required for this modern technique. Now we will explore that.

First, we need a mother plant from which we want to multiply new plants. We take a piece of tissue (explant), such as leaves, flower buds, stems, roots, or growing tips. Not all plant tissues can be used for micropropagation. Different plant species have varying abilities to regrow a whole plant from different types of tissues. Therefore, successful explants are identified by experimenting with various tissues [4].

Next, the plant tissue requires energy for growth, in the form of food. Until a complete plant develops and can produce its own food through photosynthesis, we must provide adequate nutrition using a nutrient medium that includes several components:

• Salts, which contain major nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, sulfur, and calcium, as well as other nutrients needed in smaller amounts, like boron, manganese, iron, zinc, copper, and molybdenum;

• Organic nutrients such as sucrose, which functions as an energy source, helping plants grow;

• Vitamins and minerals;

• Substances to help maintain the right pH;

• Plant growth hormones, which act as signal molecules to help in cell division, root differentiation, and in mobilizing nutrients; and

• A gelling agent that helps to make the liquid nutrient media semi-solid to support growing tissues and plants during tissue culture.

Once we have prepared the required materials, we add the nutrient media to transparent, shallow glass dishes or tubes. The surfaces of the explants are sterilized and carefully placed onto the media using sterilized forceps. This is done inside a partially enclosed work surface equipped with air filters, known as a laminar flow chamber (Figures 3A, B). This chamber helps to avoid contamination by harmful microorganisms. The explants are then kept in room with a controlled environment (the correct temperature, light intensity, and humidity), where they begin to grow (Figure 3C). We must regularly change the growth media to prevent the plants from running out of nutrients.

- Figure 3 - Micropropagation process in a tissue culture lab.

- (A) A laminar flow chamber. (B) Placing explants into nutrient media in glassware. (C) Multiplication and regeneration in a tissue culture room. (D) Plant hardening outside the laboratory. (E) Micro propagated plants growing in soil, like normal plants.

After several weeks, plants with leaves, stems, and roots will form in the glassware. At this point, we gradually remove the nutrient media and expose the plants to natural light (Figure 3D). As they begin producing their own food through photosynthesis, we must ensure they receive water, fertilization, and a suitable environment. Eventually, these plants can be transitioned to the greenhouse or field, through a process called hardening (Figure 3E). Now these plants—developed from tissue culture and nurtured with great care—are robust enough to thrive outdoors, and they are identical to each other and to their mother plant!

Try Multiplying Plants Without Seeds

Although growing certain plants like orchids requires special care, you can easily grow and multiply plants from your garden using vegetative parts. Start by taking stem cuttings from your favorite rose or hibiscus plant. Alternatively, you can take runners (long stems growing horizontally) from plants like mint or strawberries. Fill pots with a mix of soil and compost and then place the cuttings into the filled pots. Add water and leave them for a few days. Regularly check for the growth of fresh leaves and development into complete plants. Be sure to water them consistently and place the pots in sunlight for optimal growth. You will be excited to see your favorite plants multiply as many times as you desire! This process demonstrates that our beloved, useful, and even endangered plants can be propagated in large numbers from small vegetative parts.

Glossary

Plant Tissue Culture: ↑ Growing plant cells or tissues in a lab, using a nutrient-rich media, under controlled conditions of light, temperature, and humidity.

Micropropagation: ↑ Production of plant clones starting from a piece of a plant part in a tissue culture laboratory.

Totipotency: ↑ The ability of a single cell to divide, multiply, and develop into any differentiated cells of an organism.

Explant: ↑ Any living tissue taken from mother plant used as starting material to initiate plant tissue culture.

Dedifferentiation: ↑ A process in which specialized cells return back to a primitive, dividing state.

Vegetative: ↑ Plant parts other than flowers, such as leaves, stems, and roots, which are not directly involved in seed production.

Growing Tip: ↑ Ends of a plant stem or root with a bundle of dividing cells responsible for growth.

Photosynthesis: ↑ The process by which green plants use sunlight to produce their own nutrients from carbon dioxide and water.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The Research was supported by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Department of Agricultural Research and Education, Government of India. Dr. Achuit K Singh is duly acknowledged for facilitating tissue culture work at ICAR IIVR. We thank the young reviewers and science mentors for their constructive feedback on the manuscript’s improvement. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any identifiable images or data included in this article.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

References

[1] ↑ Thorpe, T. A. 2007. History of plant tissue culture. Mol. Biotechnol. 37:169–80. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-0031-3

[2] ↑ Haberlandt, G. 1902. Culturversuche mit isolierten Pflanzenzellen. Sitz-Ber. Mat. Nat. Kl. Kais. Akad. Wiss. Wien 111:69–92.

[3] ↑ Kieffer, M., Simkins, N., Fuller, M. P., and Jellings, A. J. 2001. A cost effective protocol for in vitro mass propagation of cauliflower. Plant. Sci. 160:1015–24. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(01)00347-8.

[4] ↑ Ghalagi, C., and Raju, B. M. 2022. Optimization of in vitro androgenic protocol for development of haploids and doubled haploids in indica rice hybrid, KRH 4. Mysore J. Agric. Sci. 56:39–48.