Abstract

Think about the last time you did something and then later wished you had not. Maybe you snoozed your alarm when it went off, fell back to sleep, and then woke up panicked that you were going to be late to school. You might wish you had gotten up sooner. Maybe you decided to go for the pizza on the menu but when your sibling’s pasta came out looking great, you wished you had chosen differently. These are examples of regret. Regret is something that all people feel from time to time, and it plays an important role in helping us to decide how to behave. In this article, we will explore what regret is, how we end up feeling it, and why it is so important.

What is Regret and why is it Important?

Imagine you are at a birthday party. There are lots of candies laid out on the table and you can help yourself to whatever you want. You eat lots of chocolate! Later that evening, you begin to feel sick. You think to yourself, “I wish I had stopped eating sooner”. People often compare what actually happened in life to what could have happened. This process is called counterfactual thinking. When what actually happened is worse than what could have happened, then people can feel regret (Figure 1). Thinking counterfactually is a pretty complicated process because it involves doing lots of things at once: remembering what actually happened, imagining what could have happened, comparing them, and deciding which is better. For this reason, scientists think that people only start to experience regret from around 6 years of age, which is quite late in terms of development. Think about all of the other things you can do by the time you are 6!

- Figure 1 - A child realizes they have slept longer than they should have and missed their bus to school.

- In this situation, people typically experience regret and wish they had acted differently (i.e., woken up sooner).

What Kind of Things do People Regret?

Regret is something that lots of people experience. We can have big regrets (like not working harder at school) or we can have small regrets (like picking the longer queue at lunch). Because regret is so common (and unpleasant!) scientists have spent a lot of time trying to understand it. There are two ways that researchers have tried to study regret. One way is by asking lots of people to describe a time when they have experienced regret—this is called experience sampling. When many experience samples are gathered together, researchers can look for patterns that are common across lots of people. A famous study that took this approach looked at the types of things people regret (e.g., choices about their education, career, or something in their romantic life), and whether they experienced more regret for things they did or did not do [1]. Interestingly, when people were asked about recent regrets, they often mentioned things they did, like making an embarrassing joke. But when people were asked what they regretted over the course of their whole lives, they frequently mentioned things they did not do, like not spending enough time with friends and family [2]. So next time you are worried about an awkward or embarrassing thing you said, remember: it probably will not matter much in the future.

These studies also revealed something special about regret: it was very rare for someone to report regret for something that they could not have personally changed. This suggests that feeling responsible for an outcome is necessary to experience regret. This is different from lots of other emotions like sadness, disappointment, or excitement, which people can feel even when they were not responsible for the situation that resulted in those feelings. For example, you might feel disappointed that it is raining today because you had planned to go to the beach, but you would not experience regret. In other words, when people feel regret, they think “if only I had acted differently, things would be better!”. This led scientists to believe that regret might play a special role in helping people to understand where a decision went wrong and how they can do better next time. In other words, even though regret feels unpleasant, it may actually help people make better choices in the future.

Learning From Regret

The experience sampling method also showed that people tended to say they changed their behavior after they experienced regret [3]. For example, researchers asked participants to describe a time when they had a bad experience at a restaurant, whether they experienced regret or anger at the time, and how they behaved following this experience. Participants who felt regret (rather than anger) were more likely to avoid the restaurant in the future and warn other people off going there. Evidence like this has led researchers to believe that regret is a functional emotion. What we mean by that is the experience of regret allows people to change their behavior to improve their future experiences.

Experience sampling is a good first step toward understanding psychological experiences such as emotions. But people are not always very good at understanding or explaining what they are experiencing mentally. This is particularly true for children and young people who are still learning language and developing their understanding of the world. For this reason, scientists have also used experiments to examine the idea that experiencing regret influences the future decisions people—including children—make!

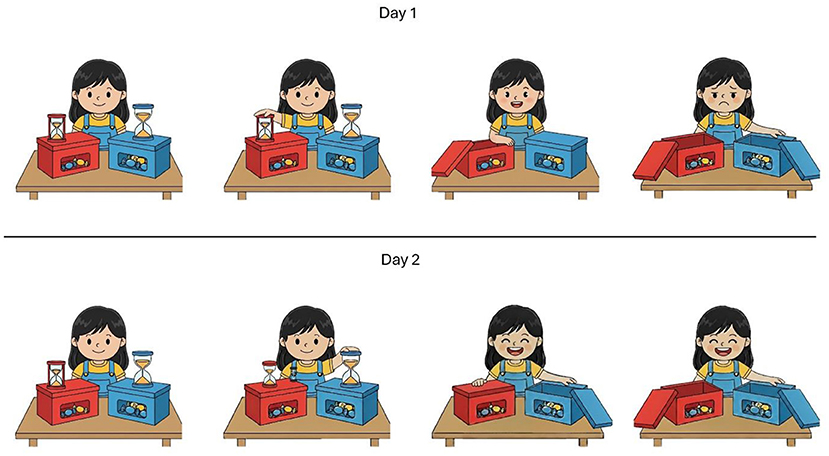

In one experiment, shown in Figure 2, 6- and 7-year-olds were told they could choose between two locked boxes to win the prize that was inside (Figure 2) [4]. One of the boxes opened after 30 s, while the other opened after 600 s. Obviously, children wanted to get the prize as soon as possible! But children did not know that the box that opened sooner only contained two candies, whereas the box that opened after 600 s contained four candies. After selecting their box and waiting for the required time, children learned how many candies they actually got, and how many they could have gotten if they had chosen differently.

- Figure 2 - An experiment to study regret in children [4].

- On day 1, participants were given the choice between two boxes, one that they had to wait a short time to open, and one that they had to wait a longer time to open. Most children picked the box with the shorter timer and got two candies. They then learned that they would have gotten four candies if they had selected the other box. The next day, the same children were given the same task. Those who regretted their choice on the previous day picked the box with the longer timer (and more candies!) on day 2.

Most of the children (73%) did not wait and therefore got a smaller prize and experienced regret. The next day, the researchers presented children with the same situation. The children who experienced regret the day before were more likely to wait longer the second time around. This shows that experiencing regret helped children to resist the temptation of a smaller reward now for a bigger reward in the future. The difference between two candies and four candies might not seem like that big of a deal, but the ability to wait for bigger rewards is a key skill that people gain as they get older. For example, people who can wait for bigger rewards are more likely to make healthy lifestyle choices and perform better in school—something that regret can help with!

Predicting Future Regret

Now you know that experiencing regret can help people make better choices the next time they are faced with a similar decision. But thinking about regret can also help people make better choices in situations they have never experienced before. Lots of research has shown that, when it comes to making a decision, people will engage in what is called mental time travel—they imagine themselves picking different options and how they would feel about each choice. Then, when it comes to actually deciding what to do in real life, they decide to go with the option they think will cause the smallest amount of regret. This mental time travel allows people to anticipate and minimize future regret. Scientists have shown that adults do this in lots of different scenarios. They have asked people how much regret they would feel if they did certain things (like smoking, getting vaccinated against a disease, or doing exercise), and then asked them how likely they are to actually do those things. Researchers can then use mathematics to predict people’s behavior from how much regret they say they would feel [5]. But it is not just adults who think this way. Research has shown that young people think about the regret that they might feel in the future when deciding whether to do things like start smoking [6].

As well as helping people to make decisions that will benefit them in the future, regret also helps people to make decisions that can benefit others. We know this from research with 6- to 7-year-old children, in which they played a sticker game that involved matching stickers to an outline of the sticker’s shape, to win a prize. Children realized they had one extra sticker than they needed to complete the game and win a prize. They were asked if they would like to keep this sticker or give it to another child. Most children chose to keep the sticker. They later found out that because they did not share, another child could not complete the game, and so was unable to win a prize like they did. Many children felt regret for not sharing. All children then played a different sharing game, and those children who experienced regret made kinder choices on this new game (they helped another child) than children who did not experience regret [7].

In summary, regret often helps people make better decisions and learn from their mistakes. However, sometimes regret is not helpful. People who have lots of regret, spend lots of time thinking about the things they regret, or feel regret more strongly report feeling less satisfied with their lives. With this in mind, it is important to avoid getting too caught up in past regrets. Instead, focus on the present and try to make the best possible decisions in the future [8]!

Glossary

Counterfactual Thinking: ↑ A way of thinking about the past in which you imagine how things could have turned out differently.

Experience Sampling: ↑ A method used by scientists to collect information about people’s thoughts and feelings by asking them to share specific experiences.

Disappointment: ↑ An emotion people feel when what really happened is not as good as what could have happened, but they could not have controlled or changed the outcome.

Functional Emotion: ↑ An emotion that helps people learn or make better decisions in the future.

Psychological: ↑ Something that is related to the mind or feelings.

Mental Time Travel: ↑ Imagining an event that is not currently happening, but that either took place in the past or could happen in the future.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. AI technology (Microsoft Copilot 365) was used for generating the images depicted in this article.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us

References

[1] ↑ Gilovich, T., and Medvec, V. H. 1995. The experience of regret: what, when, and why. Psychol. Rev. 102:379. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.379

[2] ↑ Gilovich, T., and Medvec, V. H. 1994. The temporal pattern to the experience of regret. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67:357–65. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.357

[3] ↑ Sánchez-García, I., and Currás-Pérez, R. 2011. Effects of dissatisfaction in tourist services: the role of anger and regret. Tour. Manag. 32:1397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2011.01.016

[4] ↑ McCormack, T., O'Connor, E., Cherry, J., Beck, S. R., and Feeney, A. 2019. Experiencing regret about a choice helps children learn to delay gratification. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 179:162–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2018.11.005

[5] ↑ Brewer, N. T., DeFrank, J. T., and Gilkey, M. B. 2016. Anticipated regret and health behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 35:1264. doi: 10.1037/hea0000294

[6] ↑ Conner, M., Conner, M., Sandberg, T., McMillan, B., and Higgins, A. 2006. Role of anticipated regret, intentions and intention stability in adolescent smoking initiation. Br. J. Health Psychol. 11:85–101. doi: 10.1348/135910705X40997

[7] ↑ Uprichard, B., and McCormack, T. 2019. Becoming kinder: prosocial choice and the development of interpersonal regret. Child Dev. 90:e486–504. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13029

[8] ↑ Sijtsema, J. J., Zeelenberg, M., and Lindenberg, S. M. 2021. Regret, self-regulatory abilities, and well-being: their intricate relationships. J. Happiness Stud. 23:1189–214. doi: 10.1007/s10902-021-00446-6