Abstract

Psychologists want to understand how the human mind is extraordinary among animal minds and where the unique aspects of human minds and behaviors come from. To build scientific understanding of human minds, we must study the wide range of humans across cultures, to know what all humans have in common and which aspects of human minds are diverse. However, this is not enough—studying humans across cultures tells us how humans think and act, not how they are unique among animals. To understand how humans are similar and different from other animals, we must study other animals too, especially our close primate relatives, the great apes, who have minds that are similar to ours in many, but not all, ways. So, to understand human minds and behaviors, researchers should study humans and non-humans at a scale that allows us to explore the origins of the similarities and differences of minds and behaviors across our world today.

People, Like Pets, Vary Around the World

Imagine a little girl and her dog. The girl has never visited other houses with pets, so she thinks that dogs are the only kind of human pets. We know this is not true: other animals can also be pets. Humans keep very different kinds of animals depending on what they like or where they live. Pets can vary from cats to owls to reptiles or even elephants!

The little girl does not know this yet. Her view of pets is limited, and she might need to meet different people to learn that other animals can also live at home with humans. By increasing the diversity of pets she knows about, she is increasing her understanding of what a pet is.

As psychologists, we try to understand the minds and behaviors of humans. How do we do this? Similar to the girl in our story, for many years, psychologists focused their studies on only a narrow group of people to understand various aspects of the human mind and behavior. These were usually the people who live where the researchers live—in cities with universities. However, just as not all pets are dogs, not all people think the same or behave similarly. Think about you and your friends: you all have different preferences, opinions, and tastes. Therefore, we should study human behavior in many places, across many cultures, to make sense of this variation. That means psychologists need to work with communities around the world to observe enough diversity of human thoughts and behaviors to understand better how people think and act—not just some people, but all people. But there is more. To understand who we are as humans, researchers need to know how other species think and act. Through understanding non-human species, we can better understand ourselves.

What Does it Mean to Study Human Behavior “At Scale”?

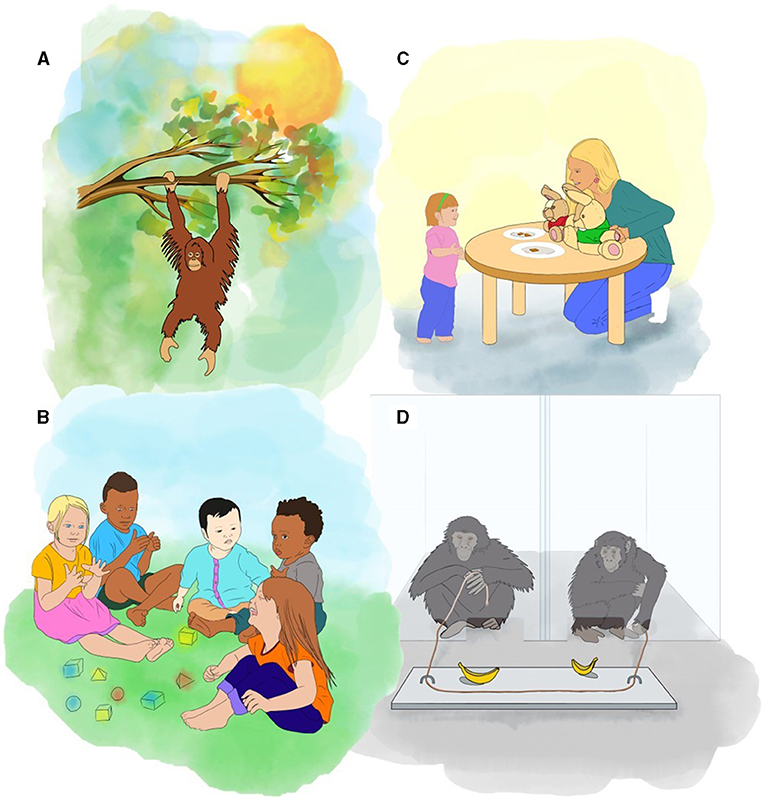

For many years, the study of human behavior has concentrated on a small group of humans—in general, university students from North America. Scientists did not do this on purpose, simply because it is generally easier to study people living nearby, and many psychologists happen to live in North America. But this creates a big problem. If researchers only focus on participants with similar lifestyles and education levels, they might assume there is not much variation in human behavior. Luckily, psychologists have realized this is not true. For example, humans in different cultures might disagree about whether green and blue are the same color, or whether seven marbles are more than eight marbles [1]. Surprising, right? That is why we work to study human behavior at scale. What we mean by that is to study humans in enough different cultures to understand how variable people really are and, of course, also how similar they are. But to truly learn who we are as humans (Figure 1), researchers need to know who we are not.

- Figure 1 - To better understand human minds, we need to study human behavior at scale, considering similarities and differences across cultures and comparing humans to other animal species.

- (A, B) For example, we can observe apes and humans in their natural environments to understand their activities, traditions, or preferences. (C, D) We can also study how humans and animals think and learn. The child is participating in a task in which she should choose one of two puppets, and the chimpanzees are cooperating to obtain bananas.

Studying Apes to Understand Humans Better

Around 5–7 million years ago, a common ancestor existed between humans and two other great apes, chimpanzees and bonobos. These common ancestors had descendants that started to separate into two evolutionary paths, one leading to modern humans and the other leading to the chimpanzees and bonobos. What happened during that period? Looking at just the genes, not much changed. We share almost 99% of our DNA with chimpanzees. However, we can observe very important differences between humans and the other two great ape species. Understanding these differences is the first step to studying human behavior at scale.

Many scientists have proposed that culture is one of the biggest differences between chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans [2]. Culture can be defined as the beliefs, traditions, and behaviors shared among group members. Think about the many traditions in your culture, such as the things you eat, how you greet each other, or how you dress. Using this definition, we can see that other animals also have cultures. Some groups of chimpanzees, for example, use stones to break nuts, while others use logs. There are also chimpanzee groups that put stiff pieces of grass in their ears and wear them all day. Each group has unique ways of behaving, which are maintained in the group—probably because they learn them from each other.

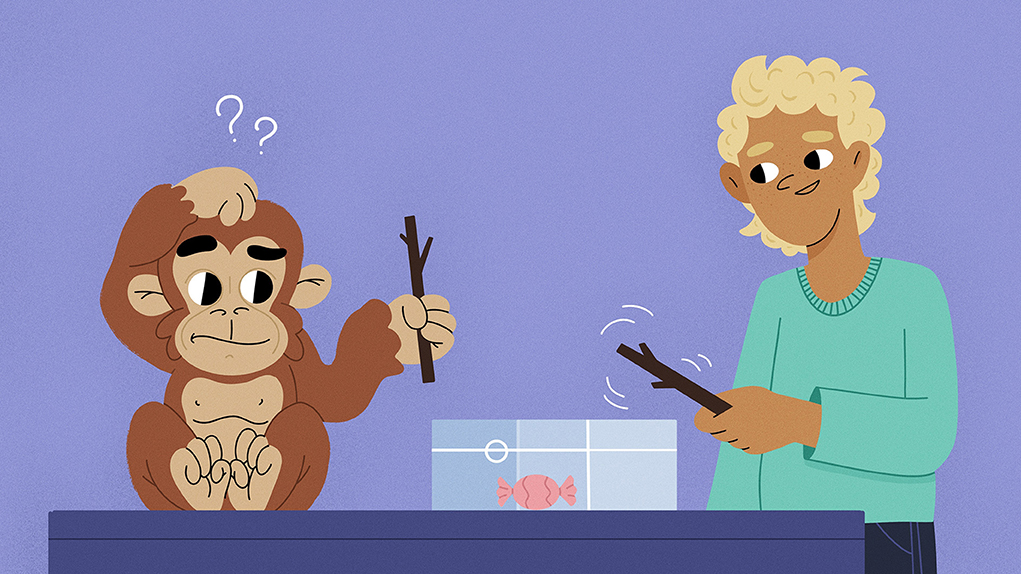

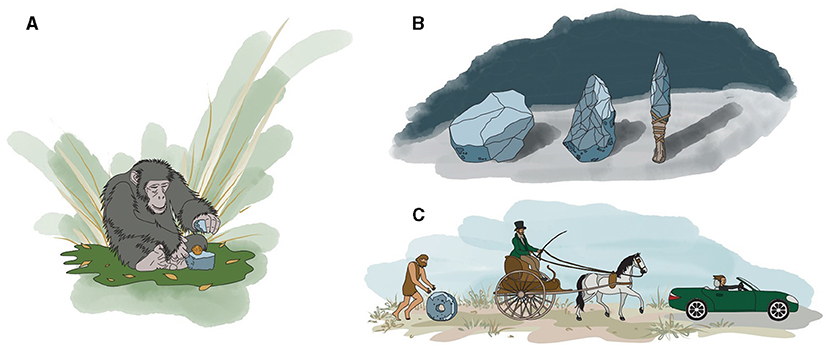

But how great ape species learn is a bit different from the way humans learn. Humans are excellent at copying each other and at teaching. Some human children tend to copy even the unnecessary actions of the experts they are learning from. For example, researchers found that, after an adult showed children how to open a transparent box, the children copied all the actions the adult made before opening the box—even the unnecessary actions, such as tapping it with a stick. Chimpanzees, in contrast, did not copy these unnecessary actions and just opened the box [3]. This means that humans learn their culture by doing things exactly like others—so even small details, like tapping a box before opening it, are transferred from one person to another. Chimpanzees are much less strict and copy things roughly, focusing more on what is done, not so much exactly how it is done. As a result, the “how” is often lost from one generation to the next. Human culture, in contrast, rarely loses the “how”, so we can keep improving on it across generations. This is part of the secret of our success as a species (Figure 2).

- Figure 2 - (A) Chimpanzee cracking nuts, using methods that likely remain the same for many generations.

- (B) Humans also started tool-making using methods similar to those of chimpanzees, but our ancestors continued to improve their methods, teaching and learning more complex methods between generations. (C) These teaching and learning processes allowed humans to grow their set of tools and technologies. For example, humans have been improving wheels over generations, which has allowed increasingly complex inventions, from chariots to cars.

By comparing humans with other animals, we now believe that the way we learn from each other is a key difference that sets humans apart from other species. But is that true for all humans in the same way, or does culture change the ways we learn from each other?

Do Children Learn the Same Way Across Cultures?

As we mentioned earlier, humans are good at imitation. But humans do not always imitate and copy the same things, or in the same way. We prefer to copy specific people, like those that are more familiar to us or who have a good reputation. For example, researchers found that, if a task is very difficult, people prefer to copy somebody who knows the task well, like a teacher. People also try to copy every step of a difficult task as closely as possible. Instead, if the task is very easy, people may realize that they do not need to follow all the steps precisely.

Furthermore, how people learn is also influenced by where they live. From early on, children learn and interact with the world very differently, depending on where they are born and the culture they belong to. For instance, as far as we know, children around the world sometimes copy actions that are not necessary to fulfill a goal, just because that is how someone else did it—like the children tapping the box before opening it. This phenomenon is known as over-imitation. However, recent studies found that children from different cultural groups vary in how much they do this [4, 5]. Researchers studied children from two communities in Congo—the Aka and the Ngandu. The Aka are hunter-gatherers, which means they rely primarily upon hunting and gathering to get food. The Ngandu are farmers. With the help of people from the Aka and Ngandu communities who participated as research assistants for the study, the researchers found that children from Aka communities copied unnecessary actions less often than children from nearby Ngandu communities. One possibility is that Aka children did this less because they usually learn differently than Ngandu children do. While children in both communities learn from others, there are no schools in the Aka community. Instead, Aka children rely a lot on observing others in their daily activities to learn about the world, whereas Ngandu children go to school and might be more used to following instructions exactly. Do you sometimes do something your teacher tells you, even though you know it could be done in a better way? So, while all humans copy each other differently than chimpanzees copy each other, humans still learn from others in slightly different ways, depending on their cultures.

What Have We Learned, and How Should We Move Forward?

Humans are part of the tree of life that connects all species on Earth. We have many things in common with other organisms, including our evolutionary cousins chimpanzees and bonobos. Yet, we do things that no other species seem to do. To understand these deep similarities and unique differences, scientists must increase the scale of their comparative research, to include many species and many human cultures, to better answer the questions they are asking [6, 7]. Understanding who we are as humans requires understanding how we are similar and different from other animals and from each other. How will you develop your own deeper understanding of who we are as a species in the world today?

Glossary

Diversity: ↑ Variety of distinct cultures, species and behaviors.

Psychologists: ↑ People that study human and non-human minds, emotions and behavior

At Scale: ↑ The study of humans from different ages, cultures and in relation to other animal species.

Common Ancestor: ↑ Living being from which at least another two descent through evolutionary processes.

Culture: ↑ The beliefs, traditions, and behaviors shared among group members.

Over-Imitation: ↑ Copying even unnecessary aspects of a task one is trying to learn.

Comparative Research: ↑ Psychological research that compares across species and cultures.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Pica, P., Lemer, C., Izard, V., and Dehaene, S. 2004. Exact and approximate arithmetic in an Amazonian indigene group. Science 306:499–503. doi: 10.1126/science.1102085

[2] ↑ Tennie, C., Call, J., and Tomasello, M. 2009. Ratcheting up the ratchet: on the evolution of cumulative culture. Philos. Trans. Biol. Sci. 364:2405–15. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0052

[3] ↑ Horner, V., and Whiten, A. 2005. Causal knowledge and imitation/emulation switching in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and children (Homo sapiens). Anim. Cogn. 8:164–81. doi: 10.1007/s10071-004-0239-6

[4] ↑ Berl, R. E., and Hewlett, B. S. 2015. Cultural variation in the use of overimitation by the Aka and Ngandu of the Congo Basin. PLoS ONE 10:e0120180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120180

[5] ↑ Stengelin, R., Hepach, R., and Haun, D. B. M. 2019. Being observed increases overimitation in three diverse cultures. Dev. Psychol. 55:2630–6. doi: 10.1037/dev0000832

[6] ↑ The ManyBabies Consortium. 2020. Quantifying sources of variability in infancy research using the infant-directed-speech preference. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 3:24–52. doi: 10.1177/2515245919900809

[7] ↑ Primates, M., Altschul, D. M., Beran, M. J., Bohn, M., Call, J., DeTroy, S., et al. 2019. Establishing an infrastructure for collaboration in primate cognition research. PLOS ONE 14:e0223675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223675