Abstract

Have you ever met someone new and felt a little nervous about how they feel about you? Turns out you are not the only one. When we meet someone new, we often think we like them more than they like us back. This gap between how much we like others and think others like us is called a liking gap. It happens because we worry about the impression we make on others. Even children experience this liking gap, but it only starts around 5 years old. At this age, the liking gap is still small. It gets bigger as children get older, probably because they start to better understand that what they do influences what others think of them. So, if you feel insecure and think the person you are talking to likes you less than you like them, just remember, the other person probably feels the same way!

What is the Liking Gap?

Have you ever worried about how people feel about you after hanging out with them for the first time? If you have, you are not the only one. It turns out, after meeting someone new, most people like the other person more than they think the other person likes them back. But if both people feel that way, then at least one of them is mistaken. So it seems that when we meet new people, we suffer from an illusion called the liking gap: we imagine that others like us less than we like them back (See: Figure 1), even though this is often not the case [1–3].

- Figure 1 - The liking gap is an illusion we experience in which we like others more than we think they like us back.

The first study that discovered the liking gap was done with adults [1]. Researchers invited college students to come to a research laboratory where they chatted with another person they did not know. Afterwards, they were asked separately how much they liked this other person and how much they thought the other person liked them back. The researchers found that most students said they liked the other person, but thought the other person liked them less. The length of the conversation did not matter: students felt this way after talking for a couple of minutes, but also when they chatted for 45 min. Even more surprising was that the liking gap stuck around for a while even after the people got to know each other. Even after 6 months, students still experienced a liking gap, and it was only after 9 months that the liking gap no longer existed [1].

Do researchers also find liking gaps in real life? Researchers asked a new group of college students the same questions. The students talked to each other, but this time, they did not know they were part of a study. They were told they were taking part in a workshop on how to talk to strangers better [1]. Even in this situation, students thought that the person they were talking to liked them less than they liked them back. Finally, the liking gap is not just a trick the mind plays on us when we are talking to one person. One study showed that the liking gap still exists even in a group [2].

How Does the Liking Gap Develop in Children?

But how does this liking gap emerge and develop? Do we experience this illusion from the day we were born? Probably not. For babies, thinking about how others feel about them is probably too difficult. But what about older kids? To find out, we tested groups of children from 4 to 11 years old It took quite some time to do the testing—we only finished the study 1.5 years after we tested the first child! We asked children to play together for 5 min, and then separated them and asked how much they liked the other child, if they would like to play with the other child again, and how much they wanted to be friends with the other child. They then also guessed how the other child felt about these things.

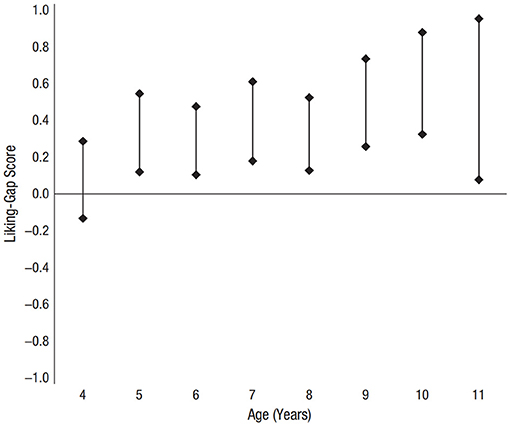

The youngest children, who were 4 years old, did not show a liking gap. But for all the older children, starting with the 5-year-olds, the liking gap was there [3]. For the 5-year-olds, this liking gap was not so big yet, but the older the children we tested, the larger the gap got. So, it seems like once children hit 5, they start to feel more insecure about how others feel about them, and this feeling gets stronger as they get older.

If that score is zero, there is no liking gap, because then that child likes the other person just as much as they think the other likes them back. However, if that score is larger than zero, then a child likes the other person more than they think the other person likes them back. So, in that case, there is a liking gap. Because not every child answers the same, we averaged the liking gap for children in each age group. Also, we did not test all the children in the world. That means that it is possible that by chance we only tested children who, for example, had very high or very low liking gaps. We therefore have some uncertainty about how big the liking gap actually is in the real world for the different age groups, even after looking at the data. To deal with this uncertainty, Figure 2 does not simply show one liking gap score per age group, but a range of liking gap scores that are the most likely for each age group. This range is shown in the graph by the lines between the 2 black dots. The more children we tested in the age groups, the more we can be certain about their scores, and thus the shorter the line. For example, we had fewer participants (8) that were 11 years old and more participants (45) who were 6 years old. That is why the line is much longer for the 11-year-olds (for whom the liking gap score is somewhere between 0.1 and 0.9) than for the 6-year-olds (for whom the liking gap score is somewhere between 0.1 and 0.5). To decide if there is a liking gap or not in an age group, we look at whether the line for the age group straddles the zero line (the horizontal line). If it does, we cannot say there is a liking gap (because the score might be positive, negative, or zero). This is what we see for the 4-year-old children. However, if the line does not straddle zero line, and the most likely values are all positive (like for children in all the other age groups), then we can say that children in those age groups probably have a liking gap.

- Figure 2 - Children show a liking gap after 5 years old.

- The lines in the graph show the 95% most likely values of the liking gap score for each age: Children’s average score on how much they liked their partner minus how much they think their partner likes them. The more uncertainty we have, the longer the line. If those lines overlap with the horizontal zero line, the difference is too small and/or we have too much uncertainty to say there is a liking gap. If the line is completely above the zero line, we can conclude there is a liking gap (adapted from the original source article: [3]).

Why Do We Have a Liking Gap?

Psychologists do not only want to know what people think or feel, but also why people think or feel that way. For the liking gap, we are not completely sure how it works, but we have some ideas about why it might happen. One idea comes from research on children. The liking gap is not the only thing that happens for the first time when children are 5 years old. At this same age, children also start to worry about what others think about them [4]. This worry about their reputation causes children to think things like “How do others feel about me? Do they want to be my friends? Do they want to hang out with me?” We can also see this in their behavior. From age 5, children become more helpful if others can see that they are being kind (so that these others will think better of them), but they are less helpful when there is no one around to see this. Perhaps it is this same worry about how others feel about them that causes children to think that others like them less than they like them. One question for future research is how changes in the brain might cause this development.

Another idea is that when we are talking to other people, we have to think so much about what we do and say that we forget to pay attention to how others are reacting to us [1]. Have you ever met someone for the first time and you both say your names, but then 5 seconds later you have forgotten their name? You were probably so busy thinking about what you have to say that you forgot to listen to the other person telling you their name. In the same way, we might often be so busy thinking about what we have to say that we fail to see how the other person reacts to us, especially when this reaction is quick or not so easy to see, like a small smile. Now, perhaps if others showed that they like us very clearly, this would not be that much of a problem. But it turns out that when other people like us, or like talking to us, they often do not tell us directly (think about it: how often have you heard someone say “I like talking to you!” directly to your face?). This makes it even harder to know how others actually feel about us.

We are therefore often not sure about how the things we do or say make other people feel. But because we care about how others feel about us, we then often start thinking about all the things we might have done “wrong” while hanging out with them, perhaps because we want to do these things “better” next time. This can sometimes be useful, but it seems that we think we do things “wrong” much more often than we do in the eyes of other people, making us feel worse than we need to.

Is the Liking Gap Good, Bad, or a Bit of Both?

So, our liking gap might not always be good for us. It might make us feel bad when talking to other people, or perhaps we become insecure in talking to new people. This might cause us to feel lonely or sad. But perhaps sometimes, the liking gap might also be helpful to us. Remember when we talked about how it can be difficult to know how others think about us? It might seem of little use, then, that we think others like us less than they actually do—in many cases we feel bad for no reason. But what if we were wrong the other way around? What if we naturally thought that others like us more than they actually do—so an opposite liking gap? Scientists think that this might even be worse. If people who are important to us do not like us as much as we think they do, then we think everything is all right and we might not put in extra effort to be nice and helpful to those people (and perhaps we spend more time with other people). But if we keep doing that, these people who are important to us might think that we do not care about them or that they are not important to us. This might cause them not to be our friends anymore and to look for other friends instead. So, if we do not worry enough about whether people like us, we might lose our friends and end up feeling lonely.

So, if you sometimes feel that others like you less than you like them back, there is no reason to panic, for two reasons. First, feeling this way might help make sure that you behave nicely and are helpful to other people, which helps building friendships. Second, you are not the only person feeling this way: the other person might feel the exact same way you do. In fact, they likely enjoy hanging out just as much as you do, or perhaps even more!

Glossary

Liking Gap: ↑ After two strangers interact with each other briefly, both report liking the other person more than they think the other person likes them.

Reputation: ↑ The opinion that people have of someone or something, based on past behavior or character.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑Wolf, W., Nafe, A., and Tomasello, M. 2021. The development of the liking gap: children older than 5 years think that partners evaluate them less positively than they evaluate their partners. Psychol. Sci. 32:789–798. doi: 10.1177/0956797620980754

References

[1] ↑ Boothby, E. J., Cooney, G., Sandstrom, G. M., and Clark, M. S. 2018. The liking gap in conversations: do people like us more than we think? Psychol. Sci. 29:1742–56. doi: 10.1177/0956797618783714

[2] ↑ Mastroianni, A. M., Cooney, G., Boothby, E. J., and Reece, A. G. 2021. The liking gap in groups and teams. Organ Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 162:109–22. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.10.013

[3] ↑ Wolf, W., Nafe, A., and Tomasello, M. 2021. The development of the liking gap: children older than 5 years think that partners evaluate them less positively than they evaluate their partners. Psychol. Sci. 32:789–798. doi: 10.1177/0956797620980754

[4] ↑ Engelmann, J. M., and Rapp, D. J. 2018. The influence of reputational concerns on children’s prosociality. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 20:92–5. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.024