Abstract

School cafeterias in the Canary Islands use mainly seafood that is imported from far-away industrial fishing operations, even though there are several nearby fishing fleets. The nearby fleets fish for tuna the traditional way, catching them one by one off of mostly small-scale fishing boats, with the hook and line technique. These boats are eco-friendly, but they tend to export their tuna—several thousand tons each year—to mainland Spain or other countries. So, in 2018, we started a project to supply local tuna and other fish steaks to about a dozen Canary Islands school cafeterias, in an attempt to reduce fish exports and imports. This is good for the environment because it decreases the amount of fuel used to move food from place to place. We hope our work will not only help school kids to eat healthier, but also improve the eating habits and health of the entire local population.

Fishing: Bigger Is Not Always Better!

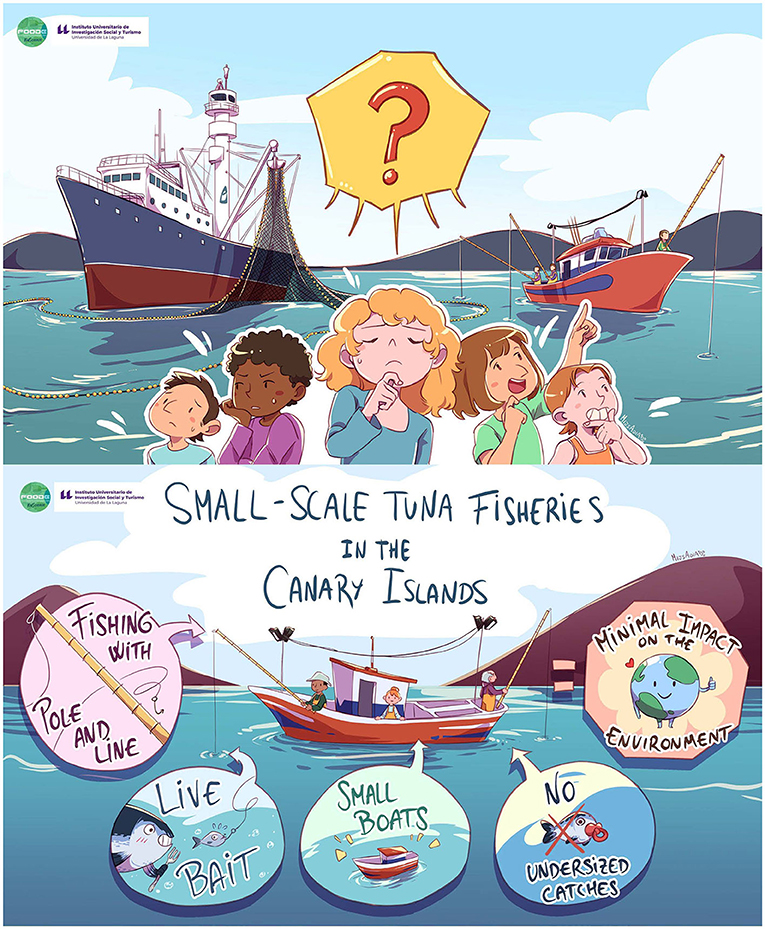

Have you ever been fishing? Did you catch anything for dinner? Even if you leave the fishing to the experts, fish that live in the ocean are a major source of healthy food for people all over the world. In “traditional” small-scale fishing, fishermen go out in small boats, with poles, lines, and hooks, and catch fish one by one, close to the coast line. This is an environmentally friendly way to fish. The boats have fairly small motors and thus do not create much pollution, and they generally do not reject fish for being too small—so fewer fish are wasted. In contrast, large-scale, industrial fishing operations are not as friendly to the environment. They use big boats with powerful engines, so that they can travel a long way and fish anywhere in the ocean, using a lot of fuel. These fishers often use fishing methods like long-lines or trawling, which accidentally catch a lot of “extra” organisms (called by-catch) and can also damage the environment (Figure 1). Large-scale fishing businesses also catch so many fish that they can have a negative impact on fish populations.

- Figure 1 - There are many differences between industrial fishing operations and traditional fishing methods.

- The traditional fishing methods used to catch tuna and other species off the coast of the Canary Islands tend to be more environmentally friendly than industrial fisheries. Artist: Marta Idaira Jiménez Sánchez.

Things have been hard for small-scale fishing fleets in recent times, due to certain legal restrictions and the fact that fewer young people have been choosing to do this type of work [1]. In the Canary Islands, where our research group lives and works, there is also a major port (between Europe, Africa, and the Americas) that has been the base for industrial fishing fleets for decades. This means there are readily available (but often lower quality) refrigerated and frozen seafood products being imported from all over the world.

Keeping It Local

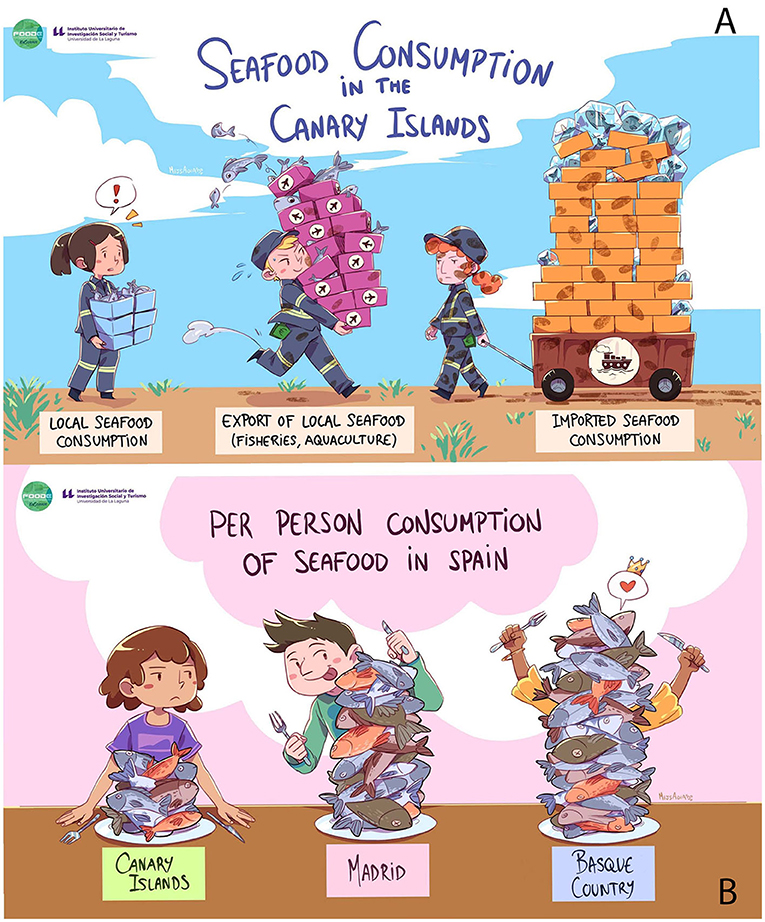

For millennia the Canary Islands have received a special type of “tourism”—large shoals of tuna that visit every year on their traditional seasonal migrations, and that have been increasingly fished by the local, traditional fishermen from early XIX century. Many tons of tuna are caught this way but, instead of being eaten fresh on the Canary Islands, these fish are mainly shipped elsewhere [2]. We found that only a small percentage of the locally caught tuna (~15%) was eaten, fresh or frozen, on the Canary Islands, while the rest was exported overseas (Figure 2) [3]. We also found that over half of the tuna eaten on the Canary Islands is imported from somewhere else in the world. Most of the imports and exports are by air or by boat, which contributes to air pollution—including the release of carbon dioxide, which contributes to global warming.

- Figure 2 - (A) Only 9–17% of seafood consumed in the Canary Islands is locally caught (around 6,000 tons).

- At the same time, more than double that amount (15,000 tons) is exported. This means that most of the fish eaten in this region come from elsewhere (34,000 tons in 2017). (B) Much less fresh seafood is eaten in the Canary Islands (5 kg per person per year in 2021) than in other areas on the mainland of Spain (10 kg per person/year in Madrid; 15 kg in the Basque country). Meanwhile, rates of obesity and diabetes are rising in the Canary Islands. Artist: Marta Idaira Jiménez Sánchez.

How did this situation come about? One reason is that there are no longer any local processing companies that can produce the cuts of fish that most customers want. Also, the Canary Archipelago is one of the regions in Spain with the lowest consumption of fish products—even though the islands are surrounded by sea (Figure 2). Hard to imagine, but true.

None of this seemed to make much sense to us. So, we decided to collaborate with local schools and fishermen to see how we could change things.

Start With the Schools

We started our initiative, Ecotunidos, to promote local fish consumption—first in some schools in Tenerife and then, hopefully, to the local society of the Canary Islands. Linking up local schools with local fishing organizations was easy and exciting to do. Both sides thought getting more fish on the menu was a good idea. In the Canary Islands, most school cafeterias make their own food, and they are significant consumers of other local products, including fruit and vegetables. Partnering with schools can help introduce local food producers to their communities, by demonstrating the importance of eating fresh, local foods to stay healthy.

The star products in our program are, of course, tuna and wahoo—especially skipjack tuna, which we know are plentiful in the Atlantic Ocean, so we do not have to worry about them becoming scarce. Skipjack tuna is really healthy to eat and does not contain a lot of pollutants like heavy metals, so it is ideal for kids [4]. In general, fish is important in a healthy diet because seafood products are good sources of vitamins, minerals, and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, all of which are needed by kids’ growing bodies. We also included other, smaller fish like sardines and mackerel, depending on what the local fishing fleet brought in and what the schools found best. What better way to keep healthy and build up protein and brain power?

In the past, school cafeterias were not big consumers of local seafood products, so the change in the menu was noticeable. Cafeteria workers had to rethink school lunch menus, which was also important because the rates of obesity and diabetes among children in the area are among the highest in Spain, due to unhealthy food habits and sedentary (non-active) lifestyles [5]. Along with helping kids build healthier brains and bodies, our program can also be a good influence on teachers and other staff and, through the kids, the healthy-eating message can spread to their families… and hopefully even to larger parts of the population.

Is Ecotunidos a Success Story?

Our research team does not frequently get the chance to work with outside partners like schools and fishing organizations, so we have learnt a lot. The pilot would not have worked without fishing organizations like Islatuna and Pescarestinga, as well as the educational community; particularly, the school canteen staff. Government entities, like the Island Council (Cabildo de Tenerife) gave us their support, along with other valuable organizations such as the Association of Chefs and Pastry Chefs (ACIRE) or Ecocomedores (ICCA). Together, we have designed both menus and class content/activities for the participating schools. Hopefully, in the future, other organizations will get excited and join in too.

This project has allowed us to see what works best and to plan for bigger and better things, like bringing in more organizations and increasing the reach of the program (Figure 3).

- Figure 3 - Our project, called Ecotúnidos, joined local schools and local fishers to bring locally caught tuna and other fish into school cafeterias.

- Artist: Marta Idaira Jiménez Sánchez.

We have come a long way since our project started in 2018. We have found ways to make life easier for school cafeteria staff who now work with local fish products like skipjack tuna, bigeye tuna, wahoo, and other local species. These schools now serve better-tasting, healthier food that is locally produced, eco-friendly, and is the same price, or even less, than the food they used to serve. We started off with 8 schools and now have 12 schools involved, with more than 2,000 schoolchildren total. The next step is to take the project to more schools and the other nearby islands, too.

What Is Next?

We have much more work to do to transfer Ecotúnidos to other islands, including adding more schools and fishing organizations. The aim is not only to put local fish on the menu at schools, but also to put it into the homes of all Canary islanders. Young kids will teach by example that local fish is best for health and for the environment.

Our fishing organizations and our schools frequently give us feedback to help us improve the program, such as creating mobile apps to make orders easier and providing training activities for cafeteria staff, for example. We continue to learn about the value of working together toward better use of our natural resources and healthier ways to care for ourselves and our environment. Do you think this kind of project could work where you live?

Glossary

Small-Scale Fishing: ↑ Commercial fishing activities developed on boats of small size (frequently under 12 meters, habitually family-owned) that generally use simple fishing gears close to the coastline, disembarking daily.

Long-Line: ↑ A long fishing line up to several miles with thousands of baited hooks, which can be located closer to the sea bottom or the water surface.

Trawling: ↑ A large net, shaped like a cone and driven by a boat with powerful engines, that usually drags the sea bottom to catch fish, shrimps or squids.

Bycatch: ↑ Unwanted catches of fish or other marine animals that are discarded by fishers because of their low value or because they are not allowed to keep them.

Wahoo: ↑ An elongated and very fast swimmer tuna fish, found in tropical and subtropical seas, that may reach up to 80 kg.

Skipjack Tuna: ↑ A small tuna with a maximum weight of around 34 kg. The typical weight in the Canary Islands is around 5–7 kg.

Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: ↑ Essential nutrients that perform key functions in humans associated with health benefits, especially for kids’ brain and retina development, pregnant women and the elderly.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

ECOTUNIDOS is part of the project FoodE: Food Systems in European Cities which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 862663.

References

[1] ↑ Said, A., Pascual-Fernández, J., Amorim, V. I., Autzen, M. H., Hegland, T. J., Pita, C., et al. 2020. Small-scale fisheries access to fishing opportunities in the European Union: is the common fisheries policy the right step to SDG14b? Mar. Policy 118:104009. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104009

[2] ↑ Pascual-Fernández, J. J., Florido-del-Corral, D., De la Cruz-Modino, R., and Villasante, S. 2020. “Small-scale fisheries in Spain: diversity and challenges,” in Small-Scale Fisheries in Europe: Status, Resilience and Governance, eds Pascual-Fernández, J. J., Pita, C., and Bavinck, M. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 253–81.

[3] ↑ Pascual-Fernández, J. J., Pita, C., Josupeit, H., Said, A., and Garcia Rodrigues, J. 2019. “Markets, distribution, and value chains in small-scale fisheries: a special focus on Europe,” in Transdisciplinarity for Small-Scale Fisheries Governance. Analysis and Practice, eds R. Chuenpagdee, and S. Jentoft (Cham: Springer), 141–62.

[4] ↑ Lozano-Bilbao, E., Delgado-Suárez, I., Paz-Montelongo, S., Hardisson, A., Pascual-Fernández, J. J., Rubio, C., et al. 2023. Risk assessment and characterization in tuna species of the canary islands according to their metal content. Foods 12:1438. doi: 10.3390/foods12071438

[5] ↑ del Río, N. G., González-González, C. S., Martín-González, R., Navarro-Adelantado, V., Toledo-Delgado, P., and García-Peñalvo, F. 2019. Effects of a gamified educational program in the nutrition of children with obesity. J. Med. Syst. 43:198. doi: 10.1007/s10916-019-1293-6