Abstract

Our world contains many ecosystems, from tropical forests to coral reefs to urban parks. Ecosystems help us in important ways, including cleaning our air and water, storing carbon, and producing food. People have been shaping most ecosystems for at least 12,000 years. Human impact has become so intense that many ecosystems are now threatened. That is why the United Nations has decided that the next 10 years are the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. But what is ecosystem restoration and how do we do it? In this article, we will tell you why ecosystem restoration is important and why it can be difficult. We will explain how it can be done well, and give examples from a range of projects. Successful restoration must include local people and requires lots of data. Restoration should not always return ecosystems back to what they were like once before.

Have you ever wondered how you can help the ecosystems around you? Or why they might need help?

Many human activities affect Earth’s natural ecosystems, including the foods we eat, the clothes we wear, and the things we do. People have been changing ecosystems around the world for more than 12,000 years—for example, by hunting animals, cutting down forests, introducing new species, and draining wetlands [1]. In the last 250 years, human impacts have become much bigger. One fifth of the world’s land has been degraded (harmed), which affects the livelihood or health of 3.2 billion people and makes animal, plant, and fungus species go extinct. That is why the United Nations (UN) declared the next 10 years the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. Countries are working together to improve ecosystems for both people and nature. This is an exciting time for ecosystem restoration! But what does ecosystem restoration mean, and how is it done?

Why Do Ecosystems Need Restoring?

Ecosystems provide us with many benefits. They clean our water and air, and they are home to many organisms, including plant species used in medicines. Ecosystems store carbon, so they combat climate change. Healthy ecosystems can cope with, and bounce back from, natural events like volcanic eruptions, landslides, hurricanes, wildfires, and floods.

People can degrade ecosystems in many ways, through pollution, climate change, overgrazing by livestock, and biodiversity loss. Degraded ecosystems do not recover as well as healthy ones. A downward spiral of ecosystem degradation can result. Over time, ecosystems can become so damaged that they cannot recover without help. This can reverse their benefits—degraded ecosystems can pollute water and release carbon. Ecosystem restoration aims to get degraded ecosystems back on track.

How Do We Know What to Aim For?

To restore an ecosystem, we need to know what the ecosystem was like when it was healthy. For example, we can plant the original tree species in a forest that was cut down, or flood wetlands that were drained. If we do not have a record of the previous state of an ecosystem, we can study healthy ecosystems of the same type. Satellite pictures can show us how ecosystems have changed over time. Talking to indigenous peoples or local people who know the area best can also provide important information.

To look back in time, scientists can also study the mud. By studying tiny fossils of pollen or algae to understand when they entered the mud, or by studying the chemistry of the soil, scientists can obtain clues telling us about what ecosystems were like before humans came along. This method was used to help restore the Coorong (pronounced “koo-rong”), a protected wetland near the sea in Australia. The Coorong is home to a group of Indigenous people called the Ngarrindjeri Nation (“en-gar-rin-dee-jeeri”). The Coorong is also used for fishing, farming, and leisure. Using clues from the mud, scientists found that this wetland had become drier than it has been for more than 7,000 years! It had become too salty for many plant and animal species to live in. The ecosystem is now being restored—the flow of fresh water to the Coorong is increasing and species are starting to return.

Many ecosystems are so damaged that we cannot restore them to what they used to be. And as the climate changes, ecosystems must change too. Many scientists argue that we should rehabilitate ecosystems instead of restoring them. This means adapting an ecosystem so that it copes with today’s conditions. After all, humans are here to stay.

How Does Ecosystem Restoration Work?

People around the world are repairing the damage done to degraded ecosystems. Ecosystem restoration projects can take many forms and can apply to ecosystems of various types and sizes. One project may focus on a single stream; another may span multiple countries. Projects often start by removing the thing that is causing the damage in the first place. For instance, keeping deer out of a forest, to protect young trees from being eaten, may allow the forest to grow again. Stopping people from taking peat from a wetland for compost or fuel can allow the wetland to recover. Sometimes this is enough, and the ecosystem restores itself. But sometimes we need a more hands-on approach to ecosystem restoration. We may need to bring back native species or change the land surface.

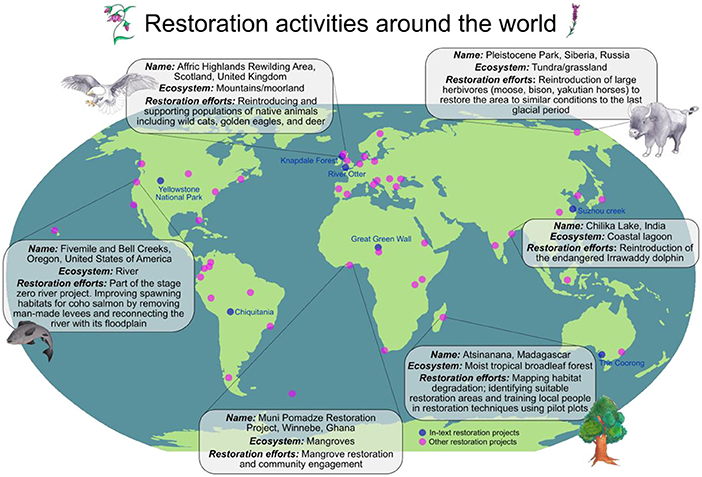

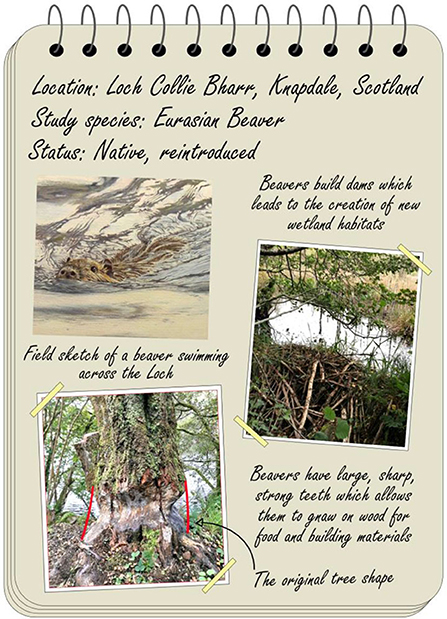

There are many ecosystem restoration projects happening all over the world (Figure 1). For example, beavers have been restored to the River Otter in Devon, England. Beavers are ecosystem engineers—they build small dams, which create ponds full of wildlife. After only 5 years, many beaver dams have been built on the River Otter. These dams have increased the number of fish and have stopped a village from flooding, protecting local people and their homes. Another beaver project was undertaken in Knapdale Forest, Scotland (Figure 2). There, beavers have built canals, supporting animals, and water-plants [2].

- Figure 1 - Ecosystem restoration projects are occurring around the world.

- Projects mentioned in the text are shown and labeled in blue. Others are shown in pink. More information about each project is included in the interactive version of this map, available at https://obaines.github.io/frontiers_restoration/restoration_map.html.

- Figure 2 - The benefits of the beaver reintroduction in Loch Collie Bharr, Knapdale, Scotland.

- Beavers create new wetland habitats by building dams and shape the ecosystem around them [Image credit (top left): Katie Smith].

Animals have also been brought back into larger areas. Wolves were missing from Yellowstone National Park (USA) since the 1920s. Without wolves eating elk, the elk multiplied. They ate too much vegetation, destroying the habitats of other animals. Without the protection of plants, riverbanks eroded and the river became wider and more damaging. In the 1990s, wolves were brought back. Now there are fewer elk, and the vegetation has recovered. Habitats are more diverse again—many animal species, including birds, beavers, and bison, have returned to Yellowstone. Plants have stabilized the riverbanks, so the river and floodplain are healthier [3].

The Great Green Wall project is very large. It aims to plant a wall of local plants in 11 countries, across the entire width of Africa. The project will restore 100 million hectares of degraded land in the Sahel, a dry ecosystem on the edge of the Sahara Desert. The project aims to increase food, water, and energy supplies. It will create 10 million green jobs by 2030, and improve gender equality. Between 2007 and 2020, 18 million hectares have been restored—that is over 25 million football pitches!

Where Do Humans Fit in?

The most successful ecosystem restoration projects tend to involve local people, including Indigenous peoples. One example is in the Chiquitania region of Bolivia, South America. There, scientists are working with the Indigenous Chiquitano (“chic-ee-tan-no”) people to restore dry forests. Seasonal dry forests are important ecosystems that store carbon and are home to unique species such as jaguars and prickly acacia trees. Indigenous peoples rely on nature and often have a close relationship with it. So, restoration projects can benefit from their knowledge.

Towns and cities can also be thought of as ecosystems! They only cover 1% of the Earth, but more than half of all people live in them. When they are healthy, these urban ecosystems bring many benefits. Urban ecosystems can clean air, soil, and water, and cool cities during heatwaves. Parks, urban forests, green roofs, and street trees all help. They are good for human physical and mental health, encouraging us to get outside, and be active. People are also protected from natural hazards such as flooding.

In the city of Shanghai, China, the government realized that Suzhou Creek was very polluted—it was smelly and no fish had been seen since 1970. In 2003, reed beds and plant ponds were created. Machines put oxygen back into the water. Fish, plants, and insects now thrive there. People living nearby can enjoy this ecosystem and learn about restoration [4]! Another project, in Nottingham, England, aims to turn an old shopping center into a new urban green-space (Figure 3). Urban ecosystem restoration will help our future. We can improve where we live, for both humans and nature.

- Figure 3 - Broadmarsh Reimagined (Nottingham, England).

- An artist’s painting of a future urban ecosystem where the Broadmarsh Shopping Center once was. Trees, shrubs, flowers, grassland, and ponds will be created, allowing wildlife to live in the city center and providing green-space for people to enjoy (Image credit: Influence https://www.influence.co.uk/).

Restoring Ecosystems For the Future

The Decade on Ecosystem Restoration aims to deliver restoration projects across the world over the next 10 years. Ten years to restore ecosystems might seem like a long time, but it is not. Trees can grow for hundreds of years! In fact, a big problem with restoration is how little time we have. To protect biodiversity and slow down climate change, we need healthy ecosystems. We need to act quickly and involve as many people as possible, including Indigenous peoples and young people. Working with local communities is key to these projects.

Young people have the most to lose and the most to gain. Perhaps you can get involved with a project near you!

Glossary

Ecosystem: ↑ A group of organisms and the physical environment where they live (rock, soils, streams, etc.), functioning as a unit.

Ecosystem Restoration: ↑ Making an ecosystem work as well as it used to. This can mean changing it back to the way it was, or helping it adapt to a new situation.

Biodiversity: ↑ The variety of life on Earth, including all the plants, animals, and fungi that live in an environment.

Ecosystem Degradation: ↑ When an ecosystem breaks down and works less well over time.

Indigenous Peoples: ↑ Groups of people with ancient ties to a location that has unique value to them and is part of their identity.

Ecosystem Engineers: ↑ Species that create, change, maintain, and destroy habitats. These organisms have a big impact on those around them and on the wider landscape.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from British Geological Survey. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

CP, OB, ED, and LH are supported by Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) ENVISION Doctoral Training Partnership Grants. LH is also supported by the British Geological Survey. The authors thank Chloe Field for reviewing a draft of this article and for her helpful suggestions, and Katie Smith and Influence (https://www.influence.co.uk/) for allowing us to reproduce their work [Beaver illustration (Figure 2) and “Broadmarsh Reimagined” illustration (Figure 3), respectively]. We would also like to thank the young reviewers for their enthusiasm and suggestions, which helped us make this article better.

References

[1] ↑ Ellis, E. C., Gauthier, N., Goldewijk, K. K., Bird, R. B., Boivin, N., Díaz, S., et al. 2021. People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118:e2023483118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2023483118

[2] ↑ Jones, S., and Campbell-Palmer, R. 2014. The Scottish Beaver Trial: The Story of Britain’s First Licensed Release Into the Wild. Available online at: https://scottishwildlifetrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/003_143__scottishbeavertrialfinalreport_dec2014_1417710135-3-compressed.pdf (accessed November 25, 2021).

[3] ↑ Beschta, R. L., and Ripple, W. J. 2012. The role of large predators in maintaining riparian plant communities and river morphology. Geomorphology. 157–158:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.04.042

[4] ↑ Li, X., Manman, C., Anderson, B. 2008. Design and performance of a water quality treatment wetland in a public park in Shanghai, China. Ecol. Eng. 35:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2008.07.007