Abstract

Each new season, youth athletes show up to team tryouts in hopes of making the team. However, there are only so many spots on the roster, and sometimes athletes get cut. Deselection, or getting cut, is the elimination of an athlete from a competitive sport team based on a coach’s decision. Deselection is an aspect of competitive sport that many youth athletes experience, and it can result in negative psychological, social and emotional consequences such as a lost sense of self, loss of friendships, and feelings of anxiety, embarrassment, and sadness. This article presents a study looking at how athletes (and their parents) coped with deselection from sport teams. The results explain some of the coping strategies youth athletes and their parents used together and how athletes can bounce back after getting cut.

Deselection: Getting Cut

Have you ever tried out for a sports team and not made it? You are not alone! Youth sport is very competitive and, each new season, athletes like yourself try out for teams in hopes of making it. However, there are only so many spots on the roster, and sometimes athletes get cut. The academic or formal term for getting cut is deselection. Deselection is defined as the elimination of an athlete from a competitive sport team based on the decisions of the coach [1]. Deselection can also happen when an athlete is invited to a tryout or a selection camp and, after training with the group for a certain length of time, is ultimately not selected as part of the final team. Given the competitive structure of youth sport, there are fewer team spots available at higher levels of sport. So, for most youth athletes, deselection is likely to happen at some point. This means that, sometime during your youth sport career, you may get cut and will need to learn to cope with that experience. Even star athletes like Michael Jordan and Lionel Messi were cut as young teenagers and still went on to have successful sporting careers.

Consequences of Deselection

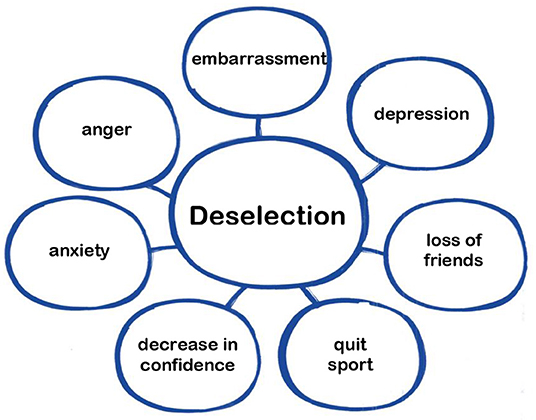

While coaches should handle deselection with care, athletes are the ones who must deal with the consequences of being cut. If you have ever been cut from a team, you will relate to some of the negative feelings other athletes have reported. Many athletes describe deselection as a negative experience with lots of psychological, social, and emotional consequences (Figure 1). For example, after being cut, youth athletes report feelings of depression, anxiety, anger, embarrassment, and humiliation. They also report feeling less confident, not feeling like themselves, losing friends, and losing connection to their school or community. Many athletes also experience a loss of athletic identity, which means they no longer feel like athletes. When some young athletes get cut from teams they no longer want to play their sports, so they stop participating either in their specific sport or in all sports. However, other athletes may continue to participate in sport but must cope with the psychological, social, and emotional consequences described above.

- Figure 1 - Possible consequences of being cut, or deselected, from a sport team.

Did you know deselection can be stressful for parents as well? Parents also have a hard time when their children get cut from teams. This can be emotionally stressful, and parents worry about the short- and long-term effects of deselection on their children [2]. We know parents are often important sources of support, but we do not know their specific roles in helping their children cope with deselection.

The Interview Process

Until recently, we knew very little about how athletes and their parents respond to and cope with the negative experience of deselection. In a recent study, we looked at how adolescent athletes and their parents coped with getting cut from sport teams [1]. We conducted interviews with 14 female athletes (ages 13–17) who had been cut from a provincial (similar to regional or state) soccer, basketball, volleyball, or ice hockey team. Only female athletes were included in the research because girls and boys cope differently with stress and adversity. Other researchers have shown that girls usually use more social support when coping, so we decided to study just girls and their experiences. We also did interviews with 14 of their parents (9 moms and 5 dads). That means we did 28 interviews in total.

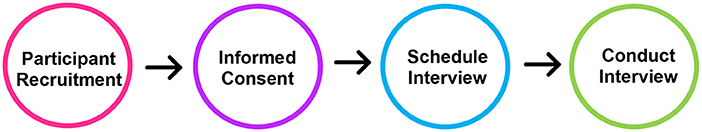

To do the interviews (Figure 2), we first had to find athletes who were the right age, played the right sports, and had just been cut from a provincial team. This process is called participant recruitment. Once we found willing athletes and their parents, we scheduled times to talk to them. Next, we had to get everyone in the study to sign a sheet saying they agreed to be in the study. This is called informed consent. The interviews themselves were the last step. We met with athletes and parents at their own houses, or they came to a research office at the university. Each interview was done separately. First, we met with each athlete and asked questions about when she got cut, how she felt, and how her parents helped her. Then we asked parents similar questions about their daughter’s experience and how they tried to help her. Each interview lasted about 1 h.

- Figure 2 - The interview process used in our study.

Because we knew that deselection was probably negative for both athletes and parents, we looked at communal coping, which is a process in which a stressful event (like deselection) is dealt with by members of a connected network, like a family [3]. Although the stressor may cause different consequences for those involved, the event is viewed as a shared stressor and coping requires shared actions. This involves an “our problem, our responsibility” perspective, shared between the athletes and their parents. Studying communal coping helped us to understand the ways parents and young athletes together dealt with being cut.

Coping Together With Deselection

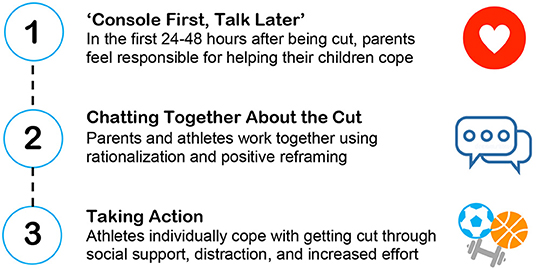

Coping with deselection seems to happen in three phases (Figure 3). If you have ever been deselected, you may remember that, right after being cut, you wanted to be left alone. The athletes in our study felt this way, too. While they experienced a rollercoaster of emotions in the first few days after deselection, they did not want to talk to their parents about their feelings; they wanted to be alone. It was important to the athletes that their parents did not ask a whole bunch of questions, but that they were there for hugs and support and waited for the athlete to be ready to talk about deselection. When athletes finally opened up about being cut, parents needed to be sensitive and respond delicately. Parents felt it was their responsibility to protect their daughters from the negative emotions experienced after deselection.

- Figure 3 - The three general phases of coping with deselection.

Once athletes decided to talk about being deselected, parents and athletes used several coping strategies to deal with their emotions together. First, they talked about various reasons for deselection. This coping strategy is called rationalization. Reasons for deselection could include being smaller or younger than other athletes, or playing a specific position for which there were limited spots (like a goalie). Second, athletes and parents talked about finding the positives in the experience. This is known as positive reframing. For example, parents highlighted the accomplishment of making it to the final round of cuts. Athletes and parents also positively reframed deselection by seeing it as an opportunity to learn and grow. Athletes could develop resiliency and learn to overcome challenges, which would help them in the future. Finally, athletes and parents recognized that just because they were cut did not mean they had to leave sport altogether; there were lots of other opportunities to play their sport at a competitive level.

After developing some cooperative coping strategies with their parents, athletes used several coping strategies themselves. Social support was one common coping strategy. Athletes texted their teammates and non-sport friends to vent about their frustration and disappointment. Their teammates and friends listened and provided reassurance that they were still good athletes and encouraged them to keep playing, which helped boost their confidence. Athletes also used distraction as another coping strategy. Athletes focused on other teams they played on, or on another sport, which helped distract them from the disappointment of being deselected. Distraction with other sports also helped because the athletes were having fun rather than being sad at home. Lastly, athletes developed a “prove coaches wrong” attitude after deselection and used the coping strategy of increased effort. Increasing effort involved things like practicing certain skills for an extra 20 min after school.

Bouncing Back After Deselection

The results of this study show that athletes and parents viewed deselection as a shared stressor, meaning it was negative and stressful for all of them, and that coping with deselection was a process that changed over time. Parents should be there for the athlete in the first few days, and then slowly and delicately talk about the deselection when the athlete is ready. Parents and athletes can cope together by engaging in rationalization and positive reframing. Finally, athletes can use social support from their teammates and non-sport friends, focus on their other teams, and put effort into training. Together, these coping strategies can help athletes bounce back after the negative deselection experience.

Although getting cut from a team can be very discouraging for a young athlete, remember that deselection does not mean you are not a good athlete—and it certainly does not mean you must stop playing the sport you love! By using the suggested coping strategies and the support of parents, young athletes can overcome deselection and continue to compete in sport at high levels. Deselection and communal coping can occur in other performance areas beyond sport, such as music, theater, and dance.

Interestingly, other research shows that athletes who were deselected during adolescence have gone on to compete at the university level. Further, these athletes learned from deselection and experienced positive growth after getting cut [4]. They became mentally tougher, developed coping skills that helped them manage other challenges in and out of sport, and strengthened their relationships with their parents, siblings, and teammates. We know that deselection will continue to happen in competitive youth sport. Now that we understand some of the ways athletes and parents can cope with the negative experience of deselection, we hope that athletes will bounce back, grow into stronger players, and continue to compete in their sports.

Funding

This work was funded by SSHRC Doctoral Fellowship (Grant no. 130679) and SSHRC Sport Participation Research Initiative (Grant no. 123768).

Glossary

Deselection: ↑ When an athlete is cut or not selected to be a member of the team.

Communal Coping: ↑ When members of a connected network (like a family) work together to manage a stressful event.

Stressor: ↑ An event or situation that causes stress.

Rationalization: ↑ Explaining or justifying a behavior or situation in a way that makes it seem reasonable or logical.

Positive Reframing: ↑ Thinking about a negative or challenging situation in a more positive way.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑Neely, K. C., McHugh, T-L. F, Dunn, J. G. H., and Holt, N. L. 2017. Athletes and parents coping with deselection in competitive youth sport: a communal coping perspective. Psychol. Sport Exercise. 30:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.01.004

References

[1] ↑ Neely, K. C., McHugh, T.-L. F., Dunn, J. G. H., and Holt, N. L. 2017. Athletes and parents coping with deselection in competitive youth sport: a communal coping perspective. Psychol. Sport Exercise. 30:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.01.004

[2] ↑ Harwood, C. G., Drew, A., and Knight, C. J. 2010. Parental stressors in professional youth football academies: a qualitative investigation of specialising stage parents. Qual. Res. Sport Exercise. 2:39–55. doi: 10.1080/19398440903510152

[3] ↑ Lyons, R. F., Mickelson, K. D., Sullivan, M. J., and Coyne, J. C. 1998. Coping as a communal process. J. Soc. Pers. Relationships. 15:579–605. doi: 10.1177/02654075981 55001

[4] ↑ Neely, K. C., Dunn, J. G. H., McHugh, T-L. F., and Holt, N. L. 2018. Female athletes’ experiences of positive growth following deselection. J. Sport Exercise Psychol. 40:173–85. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2017-0136