Abstract

Books have the power to take us on great adventures, immerse us in fantasy worlds, change our points of view, scare us, and make us laugh or cry. The characters bring the stories to life and join us on the journeys through the pages of our favorite reads. But have you ever thought about what might be happening in our brains when we let Harry Potter or Bella Swan take us on a fictional adventure? Psychologists have come up with some ingenious techniques to measure how we connect with characters in books, and they are still discovering how fictional characters might help us better understand ourselves and others. By conjuring up vivid images of different characters and letting us connect or empathize with them, books help us explore our own identities and put ourselves in other people’s shoes. Our favorite characters really can take us on the most incredible journeys!

Introduction

We are surrounded by words. Street signs, menus, text messages, textbooks, and newspapers—we read almost constantly. However, when someone asks you what you like to read, you do not really think about text messages or the street signs outside; you think about books.

On the surface, a book is just of a collection of words—much like a takeaway menu or an instruction manual—but you are unlikely to curl up on the sofa after a long day and read an instruction manual to relax! There is something different about diving into a fictional world. When we open the pages of a fiction book, we are greeted by imaginary friends—the characters waiting to accompany us on our next fictional journey.

Lots of research shows that reading is good for us. For example, reading a lot can improve your reading, spelling, and language skills [1]. However, there are other interesting effects that books might have on us, and researchers think that the fictional characters we meet when we read might have something to do with it!

Fictional Characters Help Us Understand Ourselves

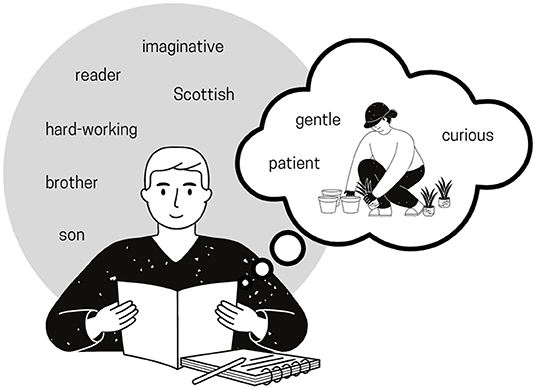

Throughout our lives we develop our identities, or our understanding of who we are. Our identities are made up of our personalities, experiences, values, goals, thoughts, and beliefs, and they continue to develop throughout our lives. Having a strong sense of your own identity can help you understand why you think, feel, and behave in certain ways. At times, it can be difficult to work out who we are. As we come into our teenage years, we often go on a bit of a “journey of discovery” to get to know ourselves. Some researchers think that reading fiction books might help us “try on” various identities in pretend environments, to see what they are like [2]. When we emotionally connect with a character in a book and feel really immersed in the story, we get the opportunity to “try on” that character’s identity for a while, to see what it feels like. Some research shows our own identities can temporarily grow to include the thoughts, feelings, and experiences of fictional characters (Figure 1) [2]. These processes also give us an opportunity to explore what makes up our own identities, helping us to learn more about who we are. Fiction books therefore give us an opportunity for personal exploration and growth, by trying out different possibilities for ourselves.

- Figure 1 - Our identities are made up of all the things that are important to our feelings of who we are, such as being hard-working, or being a sibling.

- Characters in books have a different set of personal characteristics, like being curious or gentle, and when we connect with those characters, we can try out what it might be like to have some of their characteristics too. For example, this reader might temporarily take on some of the characteristics of the fictional character and feel more curious or gentle.

Fictional Characters Help Us Understand Others

As well as helping us understand ourselves better, reading books might also help us understand and empathize with other people, by guiding us to see things from their points of view. Reading fiction books helps us get better at working out other people’s thoughts and feelings, because we get the opportunity to practice putting ourselves in their shoes. When we get absorbed in a story, we imagine what the characters are thinking and feeling to work out what might happen next. Research shows that the more we practice working out people’s thoughts and feelings in books, the better we will be at it in real life [3].

One group of researchers experimented with Harry Potter books, to see how the characters might help readers understand other people’s points of view [3]. As any Harry Potter fan will know, throughout the series, Harry encounters many wizarding folk with different characteristics—muggles, house-elves, pure- and half-blood wizards, muggle-born wizards, and even a giant or two. We also see prejudice toward some characters, for example, muggles (non-magic characters) are thought of negatively, and there is prejudice toward mud-blood (muggle-born) wizards. Despite their differences, Harry values all these characters and fights for a world free from prejudice. Interestingly, researchers have shown that identifying more with positive characters, like Harry, reduces prejudice toward groups that are often discriminated against in real life, like immigrants and refugees. In this study, the reduced prejudice toward these groups was linked with the ability to take other people’s perspectives [3]. Harry Potter is just one example of a book that might help readers improve their perspective-taking skills—maybe you can remember another book or character that helped you think about things from someone else’s point of view?

Measuring Connections With Characters

It is one thing to feel like you are connected with a character in a story, but to scientifically investigate how we are affected by fictional characters, we need a way to measure those feelings of connection. One group of researchers used a type of test called an implicit association test (IAT) to measure how much their adult participants identified with the characters in Twilight and Harry Potter and the Philosophers Stone [4]. First, participants read a section from Twilight—a book about vampires—or a section from Harry Potter—a book about wizards. Next, words were shown to the participants one at a time on a computer screen. Four types of words were shown: “me” words (like myself and mine), “not me” words (they, theirs), “wizard” words (wand, broom), and “vampire” words (blood, fangs). As soon as they saw each word, participants had to press one of two buttons on the keyboard as fast as they could (Figure 2). When participants do this quickly, without taking time to think about it, it gives researchers a measure of their implicit associations, or inner thoughts. Two types of word were assigned to each button. For example, participants had to press the left button when they saw “me” words and “wizard” words, and the right button for “not me” and “vampire” words. If participants identified strongly with wizards, they would be faster when they had to press the same button for “me” words and “wizard” words, and slower when the combination was reversed and they had to press different buttons for “me” and “wizard” words. So, this test could tell researchers how much the participants identified with wizards or vampires.

- Figure 2 - Implicit association tests can be used to measure how much participants identify with certain characteristics.

- In this example, participants must press the same button for “wizard” words and “me” words, and a different button for “vampire” words and “not me” words. Faster reaction times to “wizard” words like “wand” than to “vampire” words like “fangs” mean that the participant identifies more strongly with being a wizard than with being a vampire.

The results showed that people who read the section from Harry Potter had faster responses when they had to press the same button for “me” and “wizard” words, which suggests that they identified with being a wizard. Similarly, participants who read Twilight had faster responses when they had to press the same button for “me” and “vampire” words, suggesting that they identified more with being a vampire! They also found that the more strongly participants identified with either group, the happier it made them feel, especially when they felt that connecting with others was important to them.

What Happens In Our Brains When We Read Fiction?

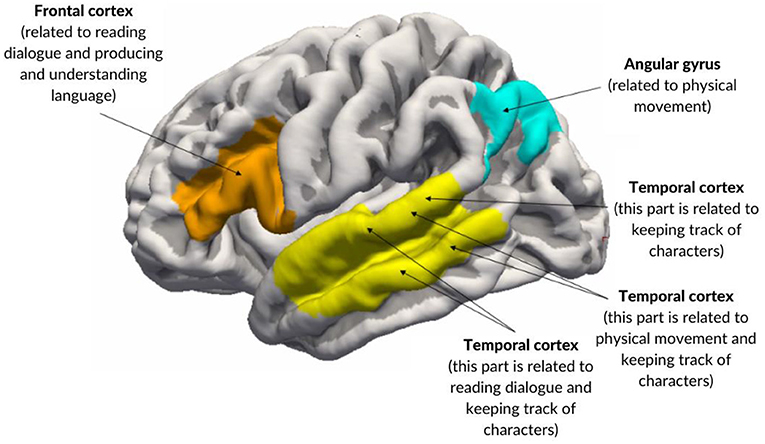

Using brain imaging technology, neuroscientists can explore what happens in our brains as we read books and connect with fictional characters. One research group used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to look at what happened in readers’ brains when they read a chapter from Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone [5]. fMRI shows which areas of the brain are active during an activity by measuring blood flow changes to those brain areas. The researchers found that reading about physical movements of characters was related to activity in an area of the brain called the angular gyrus (Figure 3, blue). This brain area is also active when we see or imagine physical movement in real life. Also, reading the dialogue in stories was related to activity in the temporal cortex and the inferior frontal cortex Figure 3, yellow and orange)—areas that are responsible for producing and understanding language. They also found different activity in the temporal cortex depending on which character was being read about. This research helps us to understand what is going on in our brains when we are absorbed in a good book, and how this might be similar to what happens in real life.

- Figure 3 - This image shows the left side (hemisphere) of the brain; the areas are mirrored on the right side as well.

- The angular gyrus (blue) is activated when we read about characters’ physical actions in books and when we imagine or see physical action in real life. The temporal and frontal cortices (yellow and orange) are activated when we read about fictional conversations and when we listen to language in real life. Part of the temporal cortex is also thought to be responsible for telling apart and keeping track of various characters in a story.

Conclusion

Connecting with characters in books can help us understand, explore, and experiment with our identities and improve our perspective-taking skills. As well as feeling like we are connected with fictional characters, studies using fMRI have shown that reading about them is related to activity in specific parts of our brains. IAT studies have also shown that reading about different characters can help us really identify with them, perhaps even taking on some of their characteristics for a while.

It is important to remember that the characters you like to read about are very personal. Just like you do not make friends with every person that you meet in real life, the characters that you like to read about, the ones that make you laugh or whom you connect with, might be different from the characters your friends like to read about. Experimenting with different topics, asking for recommendations, or trying out different formats like audiobooks or graphic novels can be brilliant ways to fall in love with reading and explore the many benefits of making fictional friends.

Glossary

Identities: ↑ The characteristics that a person feels are important to who they are. These can include gender, sexuality, race, religion, interests, skills, and beliefs.

Prejudice: ↑ A negative feeling or opinion about a person or a group, which is formed without much knowledge or thought.

Perspective-taking: ↑ Considering other people’s thoughts and emotions to understand their behavior; you could describe it as “putting yourself in someone else’s shoes.”

Implicit Association Test (IAT): ↑ A psychological test that uses reaction times to measure the unconscious links that people make between different concepts.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI): ↑ A brain imaging technique that detects blood flow changes throughout the brain. Increased blood flow shows that a region is more active.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the ESRC and managed by the SGSSS DTP under Grant ES/P000681/1, and by the Project Partner (Scottish Book Trust).

References

[1] ↑ Mol, S. E., and Bus, A. G. 2011. To read or not to read: a meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychol. Bull. 137:267. doi: 10.1037/a0021890

[2] ↑ Slater, M. D., Johnson, B. K., Cohen, J., Comello, M. L. G., and Ewoldsen, D. R. 2014. Temporarily expanding the boundaries of the self: motivations for entering the story world and implications for narrative effects. J. Commun. 64:439–55. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12100

[3] ↑ Vezzali, L., Stathi, S., Giovannini, D., Capozza, D., and Trifiletti, E. 2015. The greatest magic of Harry Potter: reducing prejudice. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 45:105–21. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12279

[4] ↑ Gabriel, S., and Young, A. F. 2011. Becoming a Vampire Without Being Bitten: the narrative collective-assimilation hypothesis. Psychol. Sci. 22:990–4. doi: 10.1177/0956797611415541

[5] ↑ Wehbe, L., Murphy, B., Talukdar, P., Fyshe, A., Ramdas, A., and Mitchell, T. 2014. Simultaneously uncovering the patterns of brain regions involved in different story reading subprocesses. PLoS ONE 9:e112575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112575