Abstract

Imagine playing a video game that is so fun you do not realize someone is calling your name. Everyone can probably think of a time like that—when you were so focused that you did not notice things happening around you. For some people, this feeling of deep attention, called hyperfocus, happens really often. In our research, we first developed a way to measure hyperfocus. Next, we tested whether people with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) hyperfocus more often. ADHD is a condition that can make it harder to pay attention to things. Despite this, many people with ADHD say that they often hyperfocus. We found that people with ADHD do have higher hyperfocus levels. In this article, we talk about our hyperfocus research, how hyperfocus can be an ADHD superpower, and our next steps toward better understanding hyperfocus and how to harness it.

Why Focus on Hyperfocus?

Picture yourself watching your favorite TV show or reading an awesome book. Those activities might cause you to focus very deeply. You might not want to stop to eat dinner or go to bed. You might not hear someone calling your name or realize that your phone is ringing. You might feel so “in the zone” that you have no clue how much time has passed! This feeling of very deep attention is called hyperfocus (Figure 1).

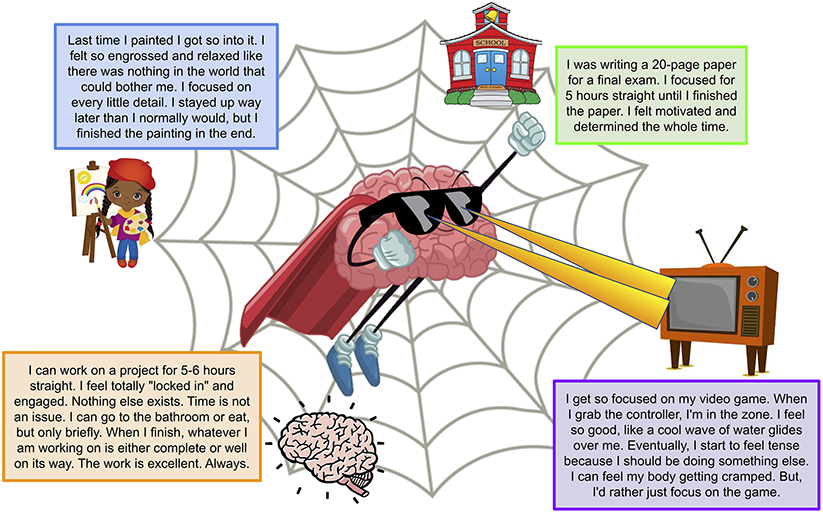

- Figure 1 - Real examples of hyperfocus.

- Each box contains a quotation from one of our study participants with ADHD. Three of the quotes tell us about hyperfocus experiences in different situations, like doing schoolwork (green), watching TV (purple), and working on a photo project (blue). The fourth quotation (orange) tells us about a person who commonly hyperfocuses and loses track of time during various enjoyable activities.

Anyone can experience hyperfocus, especially if they are doing an activity that they find really interesting. However, our research team wanted to know more about hyperfocus because lots of people with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) say that they experience hyperfocus very often. ADHD causes people to have trouble focusing their attention on certain things, such as schoolwork, and may also cause symptoms like impulsiveness or difficulty sitting still. ADHD is common; it affects about 9.4% of kids in the US—so, ~1 in every 10 kids has ADHD.

Since “deficit” means “not enough of,” it may sound strange that someone with ADHD can hyperfocus—the name suggests that these folks do not have enough attention. However, we think that people with ADHD have plenty of attention; they just have trouble controlling their attention. That is, people with ADHD have difficulty saying, “Okay, now I am going to focus only on my math homework until it is done.” They might get distracted by other things. On the flip side, people with ADHD might also put way too much attention toward something like beating a video game. They might play for 12 hours straight and totally forget to eat.

So, we know that people with ADHD can hyperfocus and that they say hyperfocus happens often for them. Until our research study, there was no good way to measure hyperfocus. Before our work, only one other research group had scientifically tested whether people with ADHD hyperfocus more than other people do [1]. That group asked 11 questions and found higher hyperfocus in people with ADHD compared to people without ADHD. Our study built on that work [2].

Measuring Hyperfocus: The Adult Hyperfocus Questionnaire

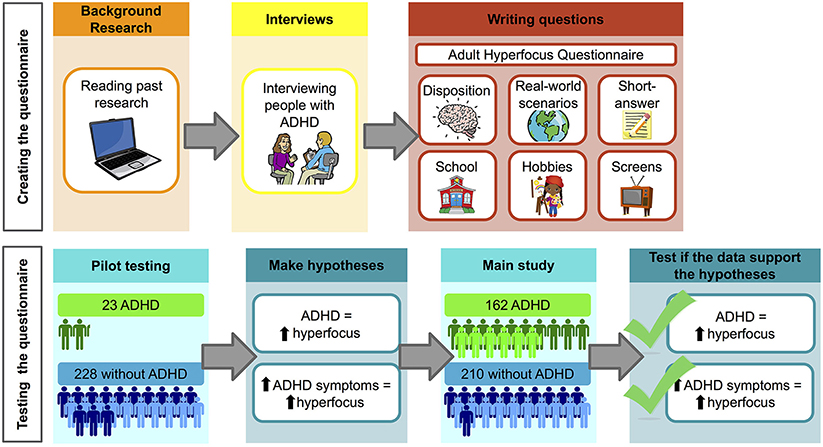

We designed a hyperfocus questionnaire to measure how often people find themselves hyperfocusing in their daily lives (Figure 2). To design this questionnaire, we first read all the science papers we could find on hyperfocus. We also interviewed 5 college students with ADHD. We discovered three important things. First, each of the students with ADHD said that they often hyperfocus. Second, multiple students told us that, when they hyperfocus, they lose track of time, and have trouble stopping the activity. Third, hyperfocus most often occurred during school, hobbies, and screen time. School included things like working on a project, writing an essay, or creating computer code. Hobbies included training for a sports competition, creating art projects, and writing music. Screen time involved activities like watching TV, playing video games, and surfing social media sites.

- Figure 2 - Our study methods.

- The top half of the chart shows the steps we used to create the hyperfocus questionnaire. The bottom half shows how we used the questionnaire to test our hypotheses in people with and without ADHD.

We used this information to write questions about hyperfocus, which we named the Adult Hyperfocus Questionnaire. The title includes the word “adult” because the people we interviewed before writing the questions were over 18 years old (specifically, young adults ages 20–31).

First, we ran a pilot study with our questionnaire. We asked our questions to 23 people with ADHD and 228 without ADHD. This pilot study had 2 goals: to make sure people understood our questions, and to calculate the number of people needed for our big study. Before doing the big study, we came up with our hypotheses. We predicted that people with ADHD would have higher hyperfocus levels. We also predicted that the more ADHD symptoms someone reported, the higher their hyperfocus score would be.

For our big study, we screened over 3,500 people to find individuals with a diagnosis of ADHD. We picked 162 people with ADHD and 210 people without ADHD for the study. These people then completed our Adult Hyperfocus Questionnaire, on which they answered a lot of questions about their ability to hyperfocus, their age, gender, education, and mental health, and their past and current ADHD symptoms. Once all the questionnaires were complete, we ran mathematical tests on the data we collected, to see if the data supported our predictions. These tests could tell us whether hyperfocus scores were higher for people with ADHD compared to people without ADHD, and whether having more ADHD symptoms was related to higher amounts of hyperfocus.

What Did We Find?

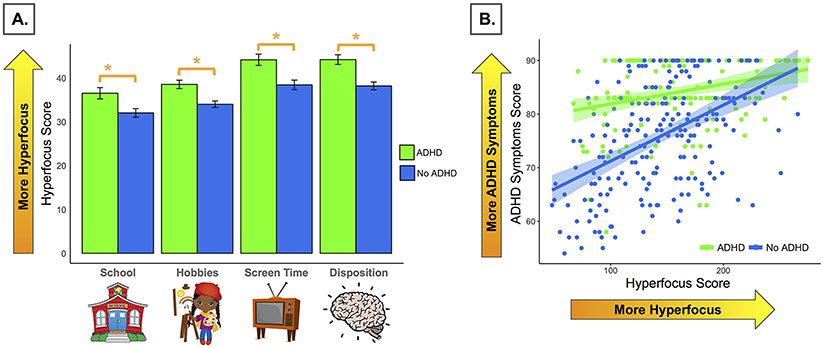

We found that people with ADHD had higher total hyperfocus scores (Figure 3A). People with ADHD reported more hyperfocus when doing schoolwork, hobbies, and screen time activities. They also had higher “dispositional” hyperfocus, meaning they rated their personalities as more likely to hyperfocus than did people without ADHD. We also found that people with more ADHD symptoms had higher hyperfocus scores (Figure 3B). This was true for both current ADHD symptoms and for ADHD symptoms participants experienced when they were children.

- Figure 3 - (A) The green bars show the average hyperfocus scores for people with ADHD.

- The blue bars show the average hyperfocus scores for people without ADHD. The stars mean that people with ADHD had higher hyperfocus scores on all the scales, compared to people without ADHD. (B) People with more ADHD symptoms had higher hyperfocus scores. Each dot represents one person. The green dots indicate people with ADHD and the blue dots indicate people without ADHD. The green and blue lines and shading tell us about the direction and strength of the relationship between ADHD symptoms and hyperfocus for each group.

So, overall, the data we collected supported our hypotheses. People with ADHD had higher hyperfocus, and more ADHD symptoms related to higher hyperfocus. Additionally, we achieved our goal of creating a questionnaire to measure hyperfocus. We think our questionnaire will be useful for doctors, therapists, and researchers who work with people who have ADHD.

Hyperfocus to the Rescue

Is hyperfocus all bad? Definitely not! Hyperfocus can be a superpower. It can help folks accomplish incredible things, like finishing a huge art project or writing a book. Many of our participants said that hyperfocus makes them very productive. They said they would not get anything done without hyperfocus. The ability to completely block out distractions and focus only on your goal can be an amazing talent and can lead to breathtaking accomplishments. It is no surprise that many famous people have ADHD, including Olympic gold medalists, artists, singers, and scientists. Their success may be partially related to their ability to hyperfocus on their professions. The key to hyperfocus is learning to control it. If you can harness your focus and use it to accomplish important things, who knows—you could be a future Olympian or a prize-winning scientist!

Hyperfocus is not an official ADHD symptom, but our results suggest that maybe it should be. Making hyperfocus an official symptom could help ADHD diagnosis and treatment. For example, if doctors know that hyperfocus—and not just a lack of attention—is a part of ADHD, they might be able to diagnose it better, particularly in adults, since ADHD is more difficult to diagnose in adults than in children.

Hyperfocus relates to neurodiversity. Neurodiversity is the idea that many brain conditions represent brain differences—not brain problems. Our research indicates that people with ADHD may not have an attention deficit, but instead might have a different attentional style. This style includes greater hyperfocus and possibly other strengths, like more creativity [3]. People with ADHD can thrive in environments that let them use these strengths effectively. Knowing about hyperfocus could help doctors and therapists teach people with ADHD how to harness their hyperfocus. Therapists could help people identify which situations involve “bad” hyperfocus, like spending way too long playing a video game, and they could help people seek situations that create “good” hyperfocus, like completing a big school project. We think it is important for people with ADHD to have their hyperfocus recognized! Many people with ADHD report that hyperfocus is a big part of their lives. But, so far, hyperfocus is not recognized as an official part of ADHD.

What is Next?

There is still a lot of work to be done before we fully understand hyperfocus. In the short term, we want to make a shorter version of our questionnaire, to make it easier to use particularly in children with ADHD. We would also like to cause hyperfocus, maybe by having research subjects play a fun video game, while we measure their performance and brain activity. Additionally, we want to know whether other characteristics are related to hyperfocus, for example, whether people with high hyperfocus are also more creative. Further research is also needed to figure out what brain mechanisms might contribute to higher hyperfocus levels in ADHD. In the long term, all of this work will help us better understand hyperfocus and its role in ADHD. This will ultimately let us help people—especially those with ADHD—harness their hyperfocus superpowers and do incredible things!

Glossary

Hyperfocus: ↑ A state of heightened, intense focus, most likely to occur when someone is doing an activity that they find really fun and interesting.

Attention-Deficit/hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): ↑ A condition that can cause various problems, including trouble paying attention to certain things, difficulty sitting for long periods of time, and a tendency to act without thinking first.

Questionnaire: ↑ A set of questions that gathers information from people, often as part of a research study.

Pilot Study: ↑ A small study that is done before running a bigger study. Pilot studies help determine whether experiments are working well and how many people are needed for a bigger study.

Neurodiversity: ↑ the idea that everyone’s brain is different. In other words, we should think about conditions like ADHD as brain differences, and not brain problems. Folks with ADHD may just have a unique way of paying attention—and sometimes, this can be a superpower!

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Holly White for engaging in many helpful conversations about our hyperfocus research.

Abbreviation

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Original Source Article

↑Hupfeld, K. E., Abagis, T. R., and Shah, P. 2019. Living “in the zone”: hyperfocus in adult ADHD. ADHD Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 11:191–208. doi: 10.1007/s12402-018-0272-y

References

[1] ↑ Ozel-Kizil, E. T., Kokurcan, A., Aksoy, U. M., Kanat, B. B., Sakarya, D., Bastug, G., et al. 2016. Hyperfocusing as a dimension of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 59:351–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.09.016

[2] ↑ Hupfeld, K. E., Abagis, T. R., and Shah, P. 2019. Living “in the zone”: hyperfocus in adult ADHD. ADHD Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 11:191–208. doi: 10.1007/S12402-018-0272-Y

[3] ↑ White, A., and Shah, P. 2006. Uninhibited imaginations: creativity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pers Indiv Diff. 40:1121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.Paid.2005.11.007