Abstract

Did language grow from gestures? That is, was using the hands, arms, or head to communicate a step toward the development of language? We studied gestures and symbols used by a chimpanzee, a bonobo, and a human child who were all taught to use symbols. A symbol can be visual or spoken; the important thing is that it means something. The apes’ symbols were pictures called lexigrams; the child’s symbols were spoken words. The chimpanzee, bonobo, and human child used many of the same gestures. They used gestures when they were young and later added symbols. The child used her voice while gesturing more than the apes did. Our study shows that the ancestor of humans, chimpanzees and bonobos probably used gestures to communicate. Our study also shows that putting sounds and gestures together was an important skill that early humans could build on to create language over thousands of years.

The question of how languages came into being is hard to study, because old languages do not leave skeletons behind. Luckily, baby apes hold clues about the history of language. Apes are like monkeys, but larger and without tails. Humans, chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans, and gibbons are all apes. Each type of ape is a species. Animals from the same species can make babies together. The other apes are closely related to people on what biologists call the Tree of Life. This Tree of Life is not a real tree. It is a map of the types of animals and other living beings in the world. The Tree of Life has so many branches on it that it looks like a tree. Each branch of the Tree of Life represents a species. Species that are similar to each other, such as dogs and wolves, deer and elk, sun fish, cat fish and gold fish, polar bears and grizzly bears, are close together on the Tree of Life. Creatures on the higher branches came into being after creatures on the lower branches, who are their ancestors (see Figure 1). The process by which a species changes over time and a new species comes into being is called evolution.

- Figure 1 - The Tree of Life.

- Image created by David Shane Smith. The Tree of Life is a map of the types of animals and other living beings in the world. Each branch of the Tree of Life represents a species. Species that are similar to each other, such as reptiles, dinosaurs and birds, or other apes and humans, are close together on the Tree of Life. Beings on the higher branches came into being after beings on the lower branches, who are their ancestors.

Humans and the other apes share an ancestor, which means that if you follow the branches of the generations of parents of humans and other apes back far enough, you come to the same animal (our shared ancestor). Humans are more like chimpanzees and bonobos than they are like the other apes, so they are closer on the Tree of Life. The three species–humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos–share an ancestor. Humans became a different species from bonobos and chimpanzees 5–7 million years ago. Bonobos and chimpanzees continued to become what they now are even after humans branched off from them. Chimpanzees and bonobos have also changed over millions of years, but in their own ways.

We can study the behavior of animals that are alive now in order to learn about the likely behavior of their ancestors. If all of the species in a branch of the tree of life can learn a skill, they probably inherited that skill from their shared ancestor. If only one species in a branch can learn a skill, the shared ancestor probably was not able to learn that skill. Instead, that one species probably developed the skill after growing apart from the other species in that branch.

Some people think humans are the only animals who can learn language. For example, many people have dogs and they know that a dog can learn to follow many commands. But following commands is not language. People use language to tell other people about things (for example, “The sky is blue.” Or “The fire needs more wood.”) People usually do not tell their dog such things because dogs communicate, but they do not use language like humans do. But we think that other animals, especially those that are closer to us on the Tree of Life, can learn simple language if they grow up in a home where others use language, and expect them to use language, like human children do. We think that the ancestor of humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos probably used gestures to learn language. Gestures are movements of the hands, arms, or body that are used to communicate.

Why Do We Think Language Grew From Gestures?

The idea that language grew from gestures is known as the gestural theory of language evolution [1]. It is an old idea. We think that language grew from gestures because non-human apes use gestures more flexibly than they use sounds [2]. For many years, researchers tried to teach non-human apes to speak using their mouths. In 1890, a researcher taught a young chimpanzee, Moses, to say “feu” (fire in French) but Moses could not learn to say it clearly. In 1916, another researcher named William Furness tried to teach four young apes to speak. After a lot of training, one ape learned to say “cup” and “papa.” But she only learned a few words. Over the next 60 years, more researchers tried to teach apes to speak by raising them with humans, but these apes only learned to speak a few words. They had great difficulty speaking words. But researchers thought that they might be able to understand many more words than they could say.

In 1966, two researchers named Beatrice and Alan Gardner adopted a baby chimpanzee, Washoe [3]. They thought that apes might not be able to speak very well because humans have more control of the parts of the body that we use to speak than apes do. Maybe, they thought, apes could do better with sign language. Like deaf human children, Washoe learned American Sign Language by playing with her caregivers and signing about the things they did. By the time she was 8 years old, Washoe could make around 150 signs! Each sign had a meaning, just like a spoken word. This was MANY more symbols than apes who had been taught to speak with their mouths had learned.

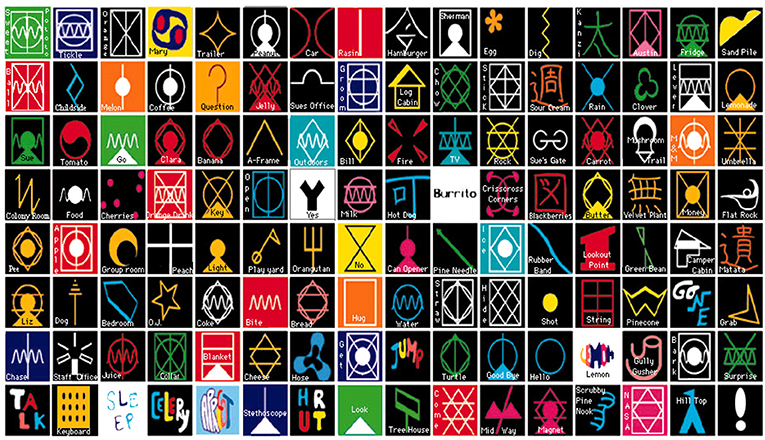

But chimpanzees have different types of hands than humans, which can make sign language hard for them. So, another researcher, Duane Rumbaugh, created a brand-new language for apes to use. Sign language and spoken language both use symbols, which stand for something but do not need to look or sound like the thing they stand for. Duane Rumbaugh created picture symbols (called lexigrams). Each lexigram had a meaning—it stood for a word, like “apple” or “go.” Lexigrams were designed to look different from each other and different from the thing they stood for. For example, the apple lexigram was not a picture of an apple, but a rectangle with a circle and a dot (Figure 2). It was important that the lexigrams not look like the thing they stood for so they would be symbols instead of just pictures. Symbols are given their meanings by the creatures who use them, rather than by how they look or sound. For example, the words feu and fire mean the same thing, but different groups of people use different words to describe fire. Apes could point to lexigrams to express themselves. They could also understand the people around them when the humans talked with their mouths or pointed to lexigrams, too.

- Figure 2 - A lexigram board.

- Lexigrams are visual symbols. Panpanzee and Panbanisha and their caregivers pointed to lexigrams on the lexigram board to share experiences and plan what to do next.

Our study [4] included a member of each of three species: a chimpanzee, Panpanzee, a bonobo, Panbanisha, and a child, GN. They were all girls. Panpanzee and Panbanisha grew up together in a home in a forest. They spent a lot of time playing with human caregivers, visiting apes who lived nearby, and traveling through the woods around their house looking for food. The apes and their caregivers used lexigrams, gestures, and speech (the apes listened but did not speak) to communicate about where they wanted to go and what they wanted to do. By communicating with the apes about things that mattered to them, the researchers helped the apes see that language is useful. Like human children, apes learn language best when they use it to communicate about things they care about with people they care about. These apes learned many ways of using language that people had thought only humans could learn, like putting symbols together to communicate new ideas [5], talking about things that are not around, and even lying!

What Did Our Study Show?

Luckily, researchers had video-taped Panbanisha, Panpanzee, and GN as they grew up. That meant we could look for and count different kinds of gestures that the apes and the child used while growing up. First, we had to define the gestures. For example, reaching is when an ape or human holds out their hand and pointing is when they point their finger toward something. So, when we saw each type of gesture, we wrote down who made the gesture, when she made the gesture, and what she made the gesture about. This procedure is called coding. Researchers use coding to turn behaviors they see on videos into numbers they can compare. We coded videos of the apes and the human from when they first used one symbol to when they started putting symbols together (starting at around 1 year of age and going to 18 months for GN or 26 months for Panbanisha and Panpanzee).

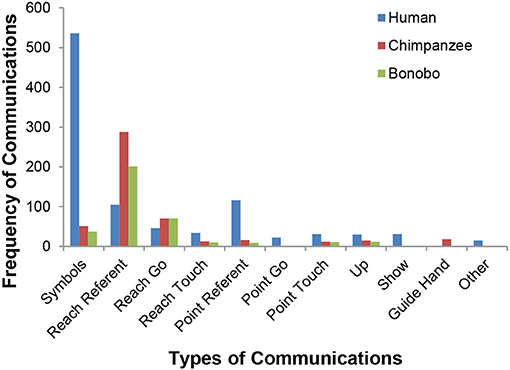

Our coding showed that Panbanisha, Panpanzee, and GN used many of the same gestures (see Figures 2, 3). In Figure 4, you can see that GN used some gestures that the apes did not, like “show” and “open.” The human child also used symbols and pointed with her finger more than the apes did. The apes reached toward things they were interested in with their whole hand more than GN did. The apes and human all gestured about things in their world before they learned to communicate about them with symbols. The ape symbols were lexigrams; the human child’s symbols were spoken words. All three used symbols more as they grew. Only the human child learned to use symbols more often than gestures.

- Figure 3 - Examples of go and up gestures.

- (A) Ape example—Panpanzee Reach gestures to go. (B) Human example—Dad asks GN if she wants pasta. She says no and points go. (C) Ape example—Panbanisha (climbing on car). Sue says, “Panban, do not do that.” Panbanisha gets down and comes to Sue with arm raised for up. (D) Human example—GN and Mom are playing with Lego blocks. GN raises arms up. Mom helps her up. Video frames from Gillespie-Lynch et al. [4].

- Figure 4 - A comparison of types of communicative gestures/symbols across species.

- The Y axis shows how many gestures/symbols each learner used across the time we observed them. The labels on the X axis mean: Symbols (words or lexigrams), Reach Referent (reaching with their whole hand toward something), Reach Go (reaching to suggest going in a particular direction), Reach Touch (reaching toward and then touching something after the caregiver responded), Point Referent (pointing with one’s index finger toward something), Point Go (pointing to suggest going somewhere), Point Touch (pointing toward and touching something), Up (raising one’s arm(s) to ask to be picked up), Show (holding an object up so someone could see it), Guide Hand (moving the caregiver’s hand into a reaching position), Other (gestures that did not happen very often like open: Moving a curved hand back and forth in front of a door knob). Graph from Gillespie-Lynch et al. [4].

What Do These Findings Tell Us?

If you think that our findings support the gestural theory of language evolution, you are right! These findings tell us that the ancestor of chimpanzees, bonobos and humans probably used gestures to communicate. Our findings also provide support for a theory we did not expect: that language evolved from both gestures and sounds (which we call the multimodal theory of language evolution). The human used her voice while gesturing much more often than the apes did. Our study showed that putting sounds and gestures together (for example, pointing at a cookie and saying “eat”) was an important skill that early humans could build on to create language over thousands of years.

Over a century of ape language research has provided evidence that the ancestor of humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos used gestures to build language [6]. Ape language research shows that apes can learn many ways of using language that people once thought only humans could learn. Our study added to research that came before it by finding evidence that language grew from the hands and mouths of our ape ancestors.

Glossary

Species: ↑ A group of animals that are similar enough to each other that they can mate and create offspring.

Gestures: ↑ Movements of the body used to communicate things to others. Please see another Frontiers for Young Minds article for more information about gestures: https://kids.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/frym.2018.00029.

Language Evolution: ↑ The gradual development of human language over time.

Symbols: ↑ Things like words or sign language signs that stand for something else and do not need to look or sound like the thing they stand for.

Lexigram: ↑ Visual symbols that have a meaning and do not look like the things they stand for just like words do not need to look or sound like the thing they stand for.

Multimodal Communication: ↑ Using more than one way of communicating at once, like gestures and the voice together.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑Gillespie-Lynch, K., Greenfield, P. M., Feng, Y., Savage-Rumbaugh, S., and Lyn, H. 2013. A cross-species study of gesture and its role in symbolic development: implications for the gestural theory of language evolution. Front. Psychol. 4:160. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00160

References

[1] ↑ Hewes, G. W. 1973. Primate communication and the gestural origin of language. Curr. Anthropol. 14:5–25.

[2] ↑ Pika, S. 2008. Gestures of apes and pre-linguistic human children: similar or different? First Lang. 28:116–40. doi: 10.1177/0142723707080966

[3] ↑ Gardner, R. A., and Gardner, B. T. 1969. Teaching sign language to a chimpanzee. Science. 165:664–72.

[4] ↑ Gillespie-Lynch, K., Greenfield, P. M., Feng, Y., Savage-Rumbaugh, S., and Lyn, H. 2013. A cross-species study of gesture and its role in symbolic development: implications for the gestural theory of language evolution. Front. Psychol. 4:160. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00160

[5] ↑ Lyn, H., Greenfield, P. M., and Savage-Rumbaugh, E. S. 2010. Semiotic combinations in Pan: a comparison of communication in a chimpanzee and two bonobos. First Lang. 31:300–325. doi: 10.1177/0142723710391872

[6] ↑ Corballis, M. C. 2002. From Hand to Mouth: The Origins of Language. Princeton, NJ; Oxford: Princeton University Press.