Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease is a condition that affects the brain, changes the way people act and behave, and makes it difficult for them to remember. Lots of research has shown that older adults who get more brain exercise are better able to fight this disease. Why does brain exercise protect against Alzheimer’s disease? One hypothesis (idea) is that brain exercise makes the right hemisphere (side) of the brain stronger, and this stronger right hemisphere helps protect people against Alzheimer’s disease. We ran a study to test this. Older adults performed a computer task which allowed us to check whether the right side of the brain was stronger than the left side. We found that people who get more brain exercise had stronger right hemispheres. These results help us to better understand why people who do lots of brain exercise are better protected against Alzheimer’s disease. We hope to use this important information to develop interventions to help fight against Alzheimer’s disease.

What is Alzheimer’s Disease?

Alzheimer’s disease is a condition that affects a person’s brain. It can be a bit puzzling to be around someone with this disease. They do not look like they are sick, but they often forget things, such as words they want to use, where they put their keys, or even the names of people they know very well. When people have Alzheimer’s disease, it can often change the way they act and behave. Because a person’s brain is damaged from the disease, it becomes difficult for that person to process and understand the world in the same way that he or she used to. Alzheimer’s is a degenerative condition, which sadly means that the condition gets worse over time. The older you get, the higher your risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Because people live much longer now than they did hundreds of years ago, Alzheimer’s is getting more and more common. Experts believe that by the year 2050, 135.5 million people in the world will have this disease. That is three times more than the amount of people who have it right now! Because of this drastic increase, lots of scientists (like us) are trying to find ways to reduce or stop this disease.

Alzheimer’s disease got its name because the German scientist who discovered it was named “Alois Alzheimer.” The brain is made up of approximately 100 billion cells, called neurons. People who have Alzheimer’s disease have an unusually high build-up of certain types of protein in their neurons, which causes abnormalities called amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (often just called plaques and tangles). These abnormalities make it difficult for the brain to do its job properly. Scientists believe that plaques and tangles make it difficult for people with Alzheimer’s disease to use their brains in certain ways.

What is Brain Exercise and How Do We Know it Helps Protect Older Adults against Alzheimer’s Disease?

Researchers worldwide are trying to understand how we can fight Alzheimer’s disease. A lot of money has been spent to find medicine that may help to cure it, but sadly nothing has been found to work well, yet. However, we know there are other things people can do to help fight Alzheimer’s, and one of these is brain exercise.

There are lots of ways that people can exercise their brains. When we are younger, we get so much brain exercise, because we are constantly learning so many new things! For example, at school alone, we learn how to read, count, spell, behave well in class, play with other children of our age, talk politely to the teacher, and read a neuroscience article. You can find other examples of brain exercise in Figure 1.

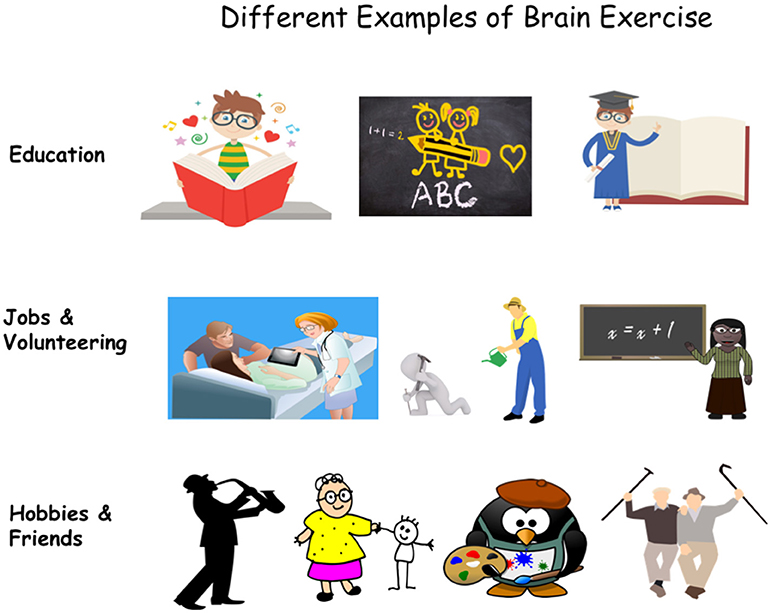

- Figure 1 - Different types of brain exercise may help protect against Alzheimer’s disease.

- Here are just a few examples of ways to exercise the brain, such as learning how to read, gardening, playing a new instrument, and socializing with friends. It is important to know that many different types of brain exercise can be good for the brain. The important thing is that they are making us use the “cognitive processes” described in Figure 2.

It has been shown in many, many studies that older adults who have had more brain exercise in their lives are better protected against Alzheimer’s disease. How do scientists know this? Some generous people donate their brains to science, so that when they die, scientists can examine their brains for research. Scientists examining brains post-mortem (which means after-death) can measure exactly how much Alzheimer’s disease someone has, by looking at how many plaques and tangles there are). These studies have shown that people who have the very same amount of Alzheimer’s disease in their brains may be affected by the disease very differently. One person might be very forgetful, will do very badly on the memory tests taken in a doctor’s office, and will behave in unusual ways. Another person with the same amount of damage in the brain might seem completely fine and do very well on the memory tests. So, why is this? Brain exercise! The scientists found that those people with lots of plaques and tangles, who did not show Alzheimer’s symptoms before they died, usually had more brain exercise during their lives.

It is important to mention that, even though keeping the brain sharp, fit, and healthy

So, if science has already shown that brain exercise protects against Alzheimer’s disease, then why are we doing another research study? What we still do not know is why brain exercise protects against the disease. What are the helpful changes within the brain when we do brain exercise?

The brain is made up of different regions, and each region is specialized for a certain function. For example, there are brain regions that are best for listening, seeing, understanding, speaking, and controlling movement.

The brain is made of two hemispheres (halves). Each half has different parts that look similar but do slightly separate things and are responsible for different cognitive processes. For example, in both halves of the brain, there is an area called the frontal cortex. The frontal cortex on the left side of the brain is primarily responsible for language (talking, reading, and understanding others when they talk). The frontal cortex on the right side is more important for paying attention, staying focused, and monitoring mistakes.

In 2014, Ian (one of the authors, see the author biography) came up with a hypothesis (idea) about how brain exercise affects the brain and makes people better able to fight against Alzheimer’s disease [1]. The hypothesis was that brain exercise might help compensate for Alzheimer’s disease by making the right hemisphere of the brain stronger. You can read more about this hypothesis in Figure 2.

- Figure 2 - What cognitive processes does the brain use during brain exercise? When we exercise our brains, we typically use five “cognitive processes” shown in green in this figure.

- Chess is one example of an activity that will use these cognitive processes, but other examples include learning an instrument, learning at school, and many other types of brain exercise (see Figure 1). All five cognitive processes use the right hemisphere, so doing brain exercise strengthens networks within the right side of the brain. Ian thinks the reason brain exercise may help protect people from brain diseases when they are older are because it strengthens the right hemisphere.

What Did We Want to Know From Our Experiment?

We decided to check whether Ian’s hypothesis was correct by running an experiment [2]. We specifically wanted to check whether people who had more brain exercise had, like Ian suspected, stronger right hemispheres. In this experiment, we invited people between the ages of 65 and 85 to come visit us at our university (Trinity College Dublin) in Dublin, Ireland.

The things we wanted to know were:

- How much exercise had their brains been getting?

When these people came in, we asked them lots of questions about what they did in their lives. You can see the whole questionnaire [3], but here are some examples of these questions: For every question, we asked them first if they did the activity, and then how often they did it.

Do you drive? Do you do any artistic activity, like playing an instrument, painting, or writing? Do you read books? Do you have any pets? Do you knit? Do you do gardening? Do you spend time with your grandchildren? - Are these people’s right hemispheres stronger than the left hemispheres?

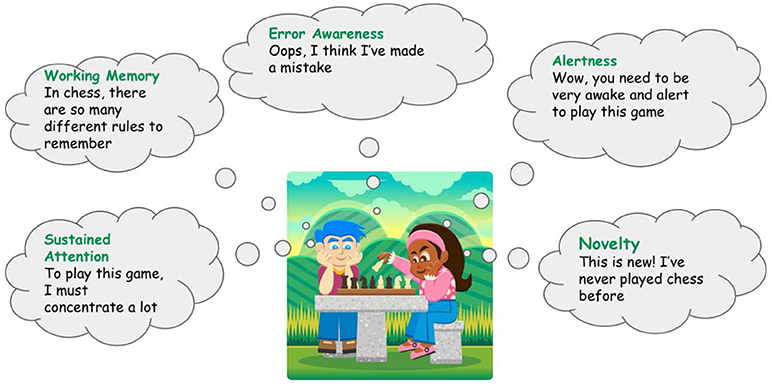

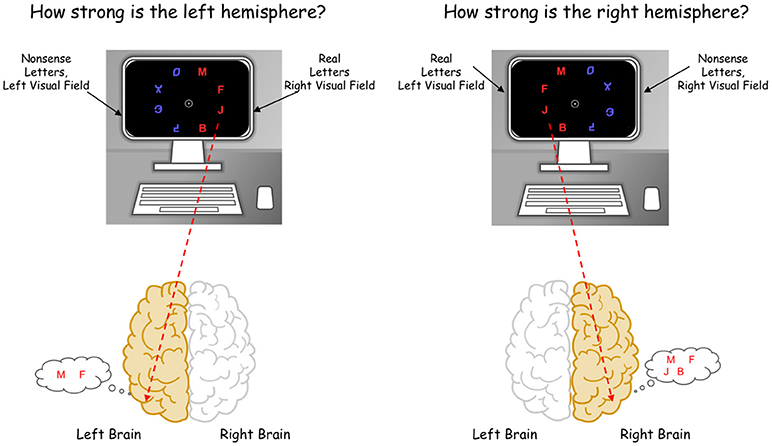

To examine if the right hemisphere of the brain was stronger than the left, we used a computer test. Before describing this test, it is important for you to understand how your brain sees the world (see Figure 3). When information comes into your eyes from the left side of the world, your eyes send this information to the right hemisphere of the brain. The opposite happens with information from the right side of the world, which is sent to your left hemisphere.

- Figure 3 - The computer task we use to assess whether the right or the left hemisphere of the brain is stronger.

- We know that, when we look at things on the left-hand side, the right side of the brain is working hard. The opposite is true too: when we process things on the right-hand side, the left side of the brain is working hard. In our experiment, we asked older adults to look at a computer screen. Letters appeared either on the left or right side of the screen, and the people called out as many letters they could, while ignoring the nonsense letters that appeared at the same time. If a person identified more letters on the left-hand side, compared with the right-hand side of the screen that meant that the person’s right hemisphere was stronger. In contrast, if a person identified more letters on the right-hand side of the screen, compared with the left-hand side that meant the person had a stronger left hemisphere.

In our experiment, the older adults saw letters on a computer screen. There were always four letters. The most important thing about the test was that the letters appeared either on the right side of the computer screen (so that information would be sent to the left hemisphere), or the left side (so that information would be sent to the right hemisphere). The letters appeared on the computer screen very quickly, and our participants only saw them for a very short time. The participants called out as many letters as they could. Sometimes, we showed the participants the letters for very short times so that it was very difficult to see them. Other times, we showed the letters for slightly longer times. The participants really had to concentrate, that is, challenge their brains! This test was created in Denmark by an experimental psychologist and mathematician named Professor Claus Bundesen [4]. We used a computer program to do some advanced math calculations, to check whether the study participants were better at seeing the letters when they appeared on the right side (which would mean a stronger left hemisphere) or the left side (which would mean a stronger right hemisphere).

What Did We Find?

What were our results? We found that older adults who get more brain exercise see things faster on the left side of the screen, compared with the right side of the screen. The more brain exercise an older adult has gotten during his or her lifetime, the stronger the right hemisphere becomes.

This was an exciting result, because it suggests that brain exercise does strengthen the right hemisphere, and perhaps this is why brain exercise protects against Alzheimer’s disease.

What should we do next? This is only a small piece of the jigsaw puzzle. Now we know that the right hemisphere is stronger in older adults who get more brain exercise. The next question is which parts of the right hemisphere are most important? For this question, it would be very helpful to use an imaging device called an MRI machine to take pictures of the brain before, during, and after brain exercise. These pictures would give us more detailed knowledge about exactly what changes in the brain with brain exercise.

Glossary

Neuron: ↑ A particular type of nerve cell found in the brain. Neurons can communicate with each other.

Proteins: ↑ The building blocks that help cells (including neurons) form and function correctly.

Amyloid Plaques: ↑ One of the signs of Alzheimer’s disease in the brain. These are sticky clumps of proteins that build up outside the neurons, causing them to die. The body cannot break down these plaques in the brain, so they build up and get bigger.

Neurofibrillary Tangles: ↑ These are another sign of Alzheimer’s disease in the brain. Unlike plaques, tangles occur inside the neurons. They make the neurons deformed and prevent them from doing their jobs.

Hemisphere: ↑ The brain is divided into two halves, which are referred to as hemispheres (the word comes from Greek and literally translates to half a sphere).

Cognitive Process: ↑ The term used to describe all of the tools we use to think. Examples of cognitive processes are paying attention (concentrating), making judgments (“is my orange bigger than John’s apple?”), remembering (“The capital of Ireland is Dublin”), reasoning (“The butter is melted and the milk tastes horrible, perhaps the fridge is broken”), and so on.

Compensate: ↑ To put in extra work to reduce the negative impact of something. Even though there might be Alzheimer’s disease-related damage (plaques and tangles) in certain parts of the brain, if the frontal regions are strong they can compensate for this damage.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Farah Hawi and Yashvi Joshi for their helpful thoughts and advice on communicating our findings to a younger audience. We thank “Pixabay” for the illustrations used to create many of the images within this article. Thanks to all of our participants, particularly those at the South Dublin Senior Citizens Club, for assisting with recruitment. A special thanks to Dr. John O’Connell for his continued support and assistance. This work was supported by the European Union FP7 Marie Curie Initial Training Network Individualized Diagnostics & Rehabilitation of Attention Disorders (Grant number 606901).

Original Source Article

↑ Brosnan, M. B., Demaria, G., Petersen, A., Dockree, P. M., Robertson, I. H., and Wiegand, I. 2017. Plasticity of the right-lateralized cognitive reserve network in ageing. Cereb. Cortex 28:1749–59. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx085

References

[1] ↑ Robertson, I. H. 2014. A right hemisphere role in cognitive reserve. Neurobiol. Aging 35:1375–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.11.028

[2] ↑ Brosnan, M. B., Demaria, G., Petersen, A., Dockree, P. M., Robertson, I. H., and Wiegand, I. 2017. Plasticity of the right-lateralized cognitive reserve network in ageing. Cereb. Cortex 28:1749–59. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx085

[3] ↑ Nucci, M., Mapelli, D., and Mondini, S. 2012. Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire (CRIq): A new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 24:218–26. doi: 10.3275/7800

[4] ↑ Bundesen, C. 1990. A theory of visual attention. Psychol. Rev. 97:523–47. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.97.4.523