In this article, we will show what our brains do when we listen to someone talking to us. Most particularly, we will show how the brains of infants and children are tuned to understand language, and how changes in the brain during development serve as preconditions for language learning. Understanding language is a process that involves at least two important brain regions, which need to work together in order to make it happen. This would be impossible without connections that allow these brain regions to exchange information. The nerve fibers that make up these connections develop and change during infancy and childhood and provide a growing underpinning for the ability to understand and use language.

We humans are very social and chatty beings. As soon as we are born, we learn to communicate with our environment. Growing up, we love to talk to our friends, to our families, and to strangers. We exchange our thoughts and feelings and are eager to learn about the thoughts and feelings of others. This includes direct spoken statements by face-to-face interactions, on the telephone, or via Skype, but also written messages via post-it notes, text messages, Facebook, or Twitter. All of these types of communication require language in order to transport a message from one person to the other. Language is used by young children from a very early age on, and their language abilities develop quickly. But how do humans learn to understand language, and what are the first steps in language acquisition? How does language develop from a baby to a child and so on? Are there certain preconditions in our brains that support language? And, most importantly, why is language important? Well, the ability to understand and produce language is a huge advantage for us because it allows us to exchange information very quickly and accurately. It even allows us to pass on this information over centuries, when we write it down and preserve it. The bible, for instance, contains texts that were written many hundreds of years ago, and we can still read it. When we talk, we can talk about things that are right in front of us, or about things that are far away, things that exist, have existed or will exist, or even things that never existed in the real world and will never be. We can even talk about talking itself, or write articles that try to teach us how this tremendous ability is made possible by our brains. Because this is the place where our words come from when we speak, and also where they go to when someone else talks to us. The language ability is one of the most amazing abilities that we have.

When babies are born, they cannot talk or understand words. A baby’s communication is generally basic and non-verbal. Babies are not born with speech or language. This is something they learn from their interactions with others. Within the first year of life, babies say their first words, and they can soon speak full sentences. After only 2–3 years, babies are already quite good at verbal communication and are able to say what they want. This fast progress in language abilities is probably supported by genetic conditions that support fast language learning.

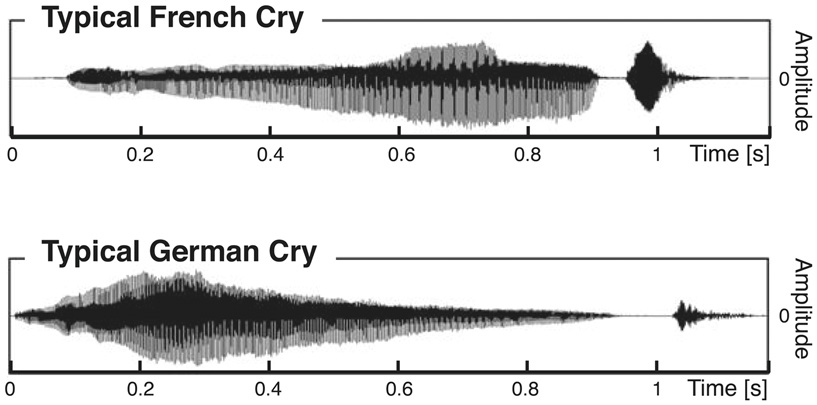

However, it is interesting to think that a baby has already taken the first steps in terms of language development even before birth [1]. This sounds impossible when we know that language needs to be learnt and does not happen automatically, unlike breathing or sleeping. But babies are actually born knowing the sound and melody of their mother tongue – and they can already “speak” by following the melodic pattern of the language. Of course, this “speaking” does not involve words, and the sound made by newborn babies is often that of crying. But this crying follows a certain melody. You might think that all babies sound similar when they cry, but when a group of German and French scientists investigated the crying sounds of German and French newborn babies [2], they actually discovered that they were different! As you can see in Figure 1, French babies show a cry melody with low intensity at the beginning, which then rises. German babies, on the other hand, show a cry melody with high intensity at the beginning, which then falls. These findings become even more interesting when you know that these cry melodies resemble the melodies of the two languages when people speak French or German: German is, like English, a language that stresses words at the beginning, while French stresses words toward their endings. To give an example, the German word for daddy is “papa” with a stress on the first syllable: papa. The French word for daddy is “papa” with a stress on the last syllable: papa. The surprising thing is that the cry melodies of French and German newborn babies follow these speech stress patterns!

- Figure 1 - The sound patterns of babies’ cries.

- The two diagrams show the intensity of the sound as a black curvature over time, in a 1.2-s frame. The wider the curves (i.e., the higher the amplitude), the more intense the sound. The upper diagram shows the sound pattern of a typical cry for French newborn babies. The cry’s highest intensity is at the end (rising from left to right). The lower diagram shows the sound pattern of a typical cry for German newborn babies. Here, unlike in the French example, the cry is more intense at the beginning (falling from left to right). These two different melodies of crying are similar to the sounds of the two languages, French and German, which appear to be learnt already before birth.

How can this be? How can babies learn the melodies and sounds of their mother tongue even before they are born? The answer is as simple as this: about 3 months before birth, while still in their mother’s womb, babies start to hear. At that time, their ears are developed enough and start working. Usually, it will mostly be the mother’s voice that reaches the baby’s ears inside the womb, but other loud sounds or voices as well. Consequently, every day of the last few months before birth, the baby can hear people speaking – this is the first step in language learning! This first step, in other words, is to learn the melody of the language. Later, during the next few months and years after birth, other features of language are added, like the meaning of words or the formation of full sentences.

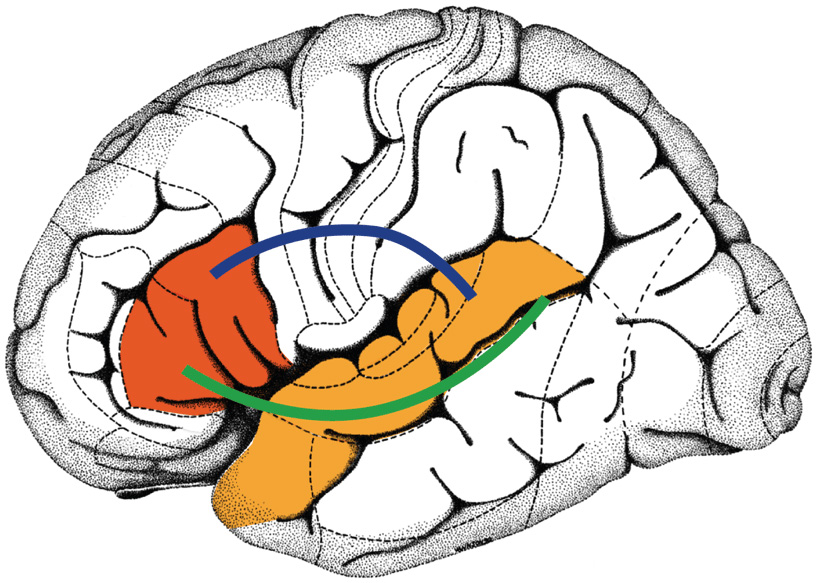

As we have seen, the development of the baby and the baby’s organs provides important preconditions for speech and language. This can be the development of the hearing system, which allows the baby to hear the sound of language from the womb. But the simultaneous development of the brain is just as important, because it is our brain that provides us with the ability to learn and to develop new skills. And it is from our brain that speech and language originate. Certain parts of the brain are responsible for understanding words and sentences. These brain areas are mainly located in two regions, in the left side of the brain, and are connected by nerves. Together, these brain regions and their connections form a network that provides the hardware for language in the brain. Without this brain network, we would not be able to talk or to understand what’s being said. Figure 2 illustrates this talkative mesh in the brain. The connections within this network are particularly important, because they allow the network nodes to exchange information.

- Figure 2 - A view of a brain, as seen from the left side.

- Two brain regions are highlighted in red and orange. These regions are strongly involved in processing speech and language. The blue and green lines illustrate connections that link the two regions with one another and form a network of language areas. There is an upper nerve connection (blue) and a lower nerve connection (green).

Now, let’s keep in mind how important this network is to fully master language. Assuming that the brain develops during infancy and childhood, we might wonder from what age onward the network of language areas is well enough established to serve as a sufficient precondition to speaking and understanding language. Is it that the network is there from a very early age on, and that the development of language is dependent on learning based on the input from the environment? Or is this network something that develops over time and provides a growing precondition that enables more and more possible language functions?

These questions can be answered by investigating the nerve fiber connections in the brain. The nerve fibers are a crucial part of the brain and form the language network. These nerve fibers can be visualized using a technique called magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI is an imaging method that allows us to take pictures of someone’s brain inside their head, like X-ray but without any rays being used. Instead, the magnetic properties of water (yes, water is slightly magnetic) are used while the person is inside a strong magnetic field created by the MR scanner.

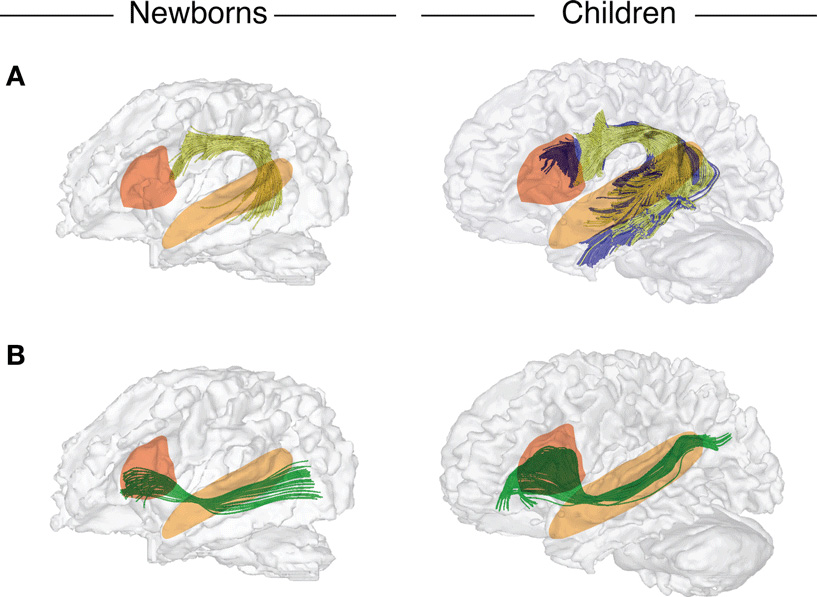

Now, using this technique, a comparison between newborn infants and older children (for example 7-year-olds who are already going to school) would show if their brain networks are the same or not. If they are the same, this would mean that there are preconditions for language in the brain from birth onward. If they are different, this would mean that the brain’s preconditions for certain language functions probably are not yet fully established at birth, and that these preconditions grow as the babies get older. The brain networks for newborns and 7-year-olds are depicted in Figure 3.

- Figure 3 - A view of the brains of newborn infants (left) and 7-year-old children (right).

- The two important language regions of the brain are highlighted in red and orange (like in Figure 2). The technique of magnetic resonance imaging provides images of the nerve connections between the two language regions. The lower nerve [green (B)] connects these regions of the brain in both newborns and children. But the upper nerve between the language regions [blue (A)] is only observed in children, not yet in infants. However, infants already show a connection to a directly neighboring region [yellow (A)]. This means that the language network in infants is not fully established yet. The important connection by the upper nerve still has to develop. On the other hand, the network shown for children is already very similar to that of adults and shows two network connections, an upper one and a lower one.

As can be seen, for both newborn infants and children going to school, the network of brain connections between the language regions is, in general, established. For newborn infants, a basic connection (green in Figure 3B) within the language network can be used. This is an important precondition from a very early age on. But the important upper connection between the language regions (blue in Figure 3A) cannot be seen in newborns. However, they already possess a second upper connection (yellow in Figure 3A) that does not connect to the red language region directly, but to a region right next to it that helps to develop and increase speech and language abilities. This means that the full language network as it is used for language abilities by older children does not exist in newborn babies yet, but it also means that they already possess a basic network. It is probably true that the full language network is an important precondition in development that allows children to learn and use more advanced language skills.

As we have seen here, the development of the hearing system and the development of the brain language network provide crucial preconditions for infants to be able to develop and improve their language abilities. Although infants already possess an important groundwork for language acquisition, more advanced language learning becomes possible as the brain continues to develop during childhood. Different stages of the language network, as shown in Figure 3, demonstrate that the language network develops over time. The nerve fiber connections in the brain change throughout our lives. During infancy and childhood, they become more and more powerful in their ability to transmit information, and it is only when we reach our teenage years that many of these nerve fibers stop developing. When we get old, they slowly start to decline. For each age for which the networks are illustrated (for example for newborn babies and for children, as in Figure 3), we only get a snapshot of a continuously changing matter. And it is not only maturation and aging that influence these networks. For instance, a therapy that is supposed to cure a disease might also alter the brain. Everything we experience and learn can potentially impact the brain and the brain networks. In other words, with each lesson we learn at school, we change our brains!

References

[1] ↑ Brauer, J., Anwander, A., Perani, D., and Friederici, A. D. 2013. Dorsal and ventral pathways in language development. Brain Lang. 127:289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2013.03.001

[2] ↑ Mampe, B., Friederici, A. D., Christophe, A., and Wermke, K. 2009. Newborns’ cry melody is shaped by their native language. Curr. Biol. 19:1994–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.064