Abstract

For the most part, we talk because we want to communicate with others: our friends, parents, teachers, even pets. Our voice carries our message to other people's ears. However, they are not the only one listening: when we talk, we can hear ourselves with our own ears as well. Do we pay attention to the sound of our own speech? Listening to what we say would be very useful, because we could listen for mistakes in our speech and make sure that we fix them so the right message gets across. How does our brain react when we hear ourselves make a mistake while talking?

When We Talk, Who is Listening?

We did an experiment to figure out what happens when we hear ourselves make a slip of the tongue – we will call it a speech error. The participants in our experiment talked through a microphone and wore headphones, which we used to play back what they said while they were talking (there was almost no delay, so they heard each word through the headphones at the same time as they said it). Our goal was to scan the brains of these participants in two conditions: when they spoke correctly, and when the words did not sound right.

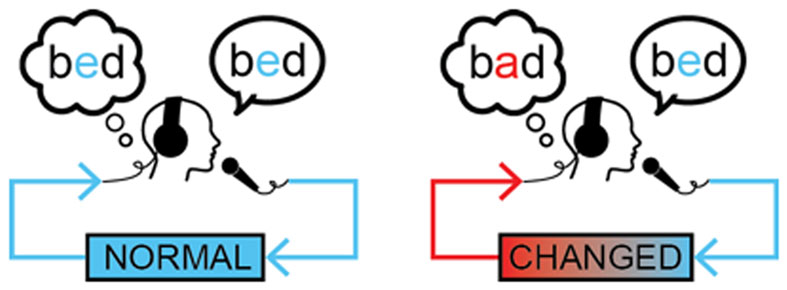

However, it is difficult to study real speech errors, because you have to wait for them to happen. So here is the trick: we fooled the participants into thinking they had made an error. Most of the time during the experiment, they heard their own voices normally, but occasionally, they said one thing and heard another. How did the trick work? First, we took the words that were picked up by the microphone, and we used a computer to change the way the words sounded. We changed the vowel (A, E, I, O, U) and left the rest of the word as it was. Then, we played the new changed sound to their headphones (see Figure 1 for an illustration and sound clips). For example, if a participant said “bed,” they might have heard “bad” come back through the headphones. With fast computers, we can record, change, and play back the words extremely quickly (seventeen thousandths of a second!). It sounds so natural that many participants did not even notice that anything out-of-the-ordinary had happened.

- Figure 1

- Diagram of a normal word production (left) and the one that has been altered to sound like an error (right).

The Brain Listens for Errors

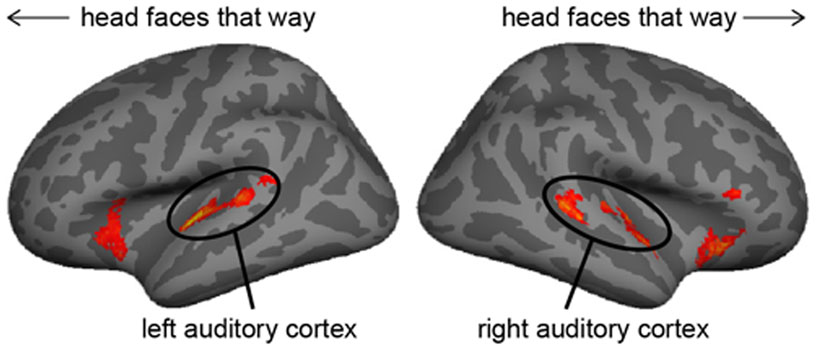

Even though most of the participants could not consciously tell that their speech had been changed, their brains noticed the difference! The auditory cortex is the part of the brain that sits behind your ears on both sides, and it processes audio – that is, sound, including speech. We used a brain imaging technique called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure the activity of this brain area when people were speaking and listening to themselves. Part of the auditory cortex activated more to errors – the times when we changed the sound – than to normal speech (Figure 2) [1, 2].

- Figure 2

- Brain areas that are more active during “errors” than during normal speaking.

What is this Increased Activation Doing?

It turns out that the more your auditory cortex is active, the more you change the way you are talking to fix your “mistakes,” undoing the changes that the computer applies. For example, let us say we asked the participants in the experiment to say the word “bed.” All spoken words are made up of frequencies, which are properties of sound that we can use to tell apart different vowels. When the computer made some of the frequencies in the sound higher, making “bed” sound like “bad,” the participants automatically lowered those frequencies, saying something more like “bid.” This canceled out the effect of the computer so that the headphones were playing something closer to the right sound: “bed.” When the computer made some of the frequencies sound lower, turning “bed” into “bid,” this time the participants raised those frequencies, saying something more like “bad.” Again, this canceled out the effect of the computer so that they heard the right sound, “bed,” through the headphones. Remember, many of them did this without even noticing that anything was going on! They did not know they were actually saying “bid” and “bad” to get the sound to come out right. Furthermore, they made these changes before the word was over: they only took about a tenth of a second to start pronouncing the word differently [3, 4].

We Can Correct Our Speech without Even Knowing it

Sometimes, we notice that something we said did not sound quite right, and we correct ourselves (“oops, what I meant was.”). In this study, we showed that people can correct an error in their speech even before they have finished saying the word, without ever even noticing that they are doing it. This suggests that, in day-to-day conversations, we can automatically correct ourselves to fix mistakes as they are happening.

We also showed that the auditory cortex becomes more active during these errors, and that people with stronger activity in this area did a better job correcting the errors. Therefore, identifying and fixing these speech errors happens with the help of the auditory cortex. Our brains probably use this automatic error-correction process all the time as we speak, keeping us on track and saving us from a lot of mistakes. Think about that the next time you hear a slip of the tongue!

Glossary

Auditory cortex ↑ The part of the brain that processes sound.

Frequency ↑ A property of sound that we can use to tell apart different notes of a song, different voices, and different vowels.

Speech error ↑ Saying one thing when you mean to say something else.

References

[1] ↑ Niziolek, C. A., and Guenther, F. H. 2013. Vowel category boundaries enhance cortical and behavioral responses to speech feedback alterations. J. Neurosci. 33:12090–8. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2137-13.2013

[2] ↑ Tourville, J. A., Reilly, K. J., and Guenther, F. H. 2008. Neural mechanisms underlying auditory feedback control of speech. Neuroimage 39:1429–43. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.054

[3] ↑ Purcell, D. W., and Munhall, K. G. 2006. Compensation following real-time manipulation of formants in isolated vowels. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 119:2288–97. doi:10.1121/1.2173514

[4] ↑ Cai, S., Ghosh, S. S., Guenther, F. H., and Perkell, J. S. 2011. Focal manipulations of formant trajectories reveal a role of auditory feedback in the online control of both within-syllable and between-syllable speech timing. J. Neurosci. 31:16483–90. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3653-11.2011