Abstract

When you hear the word “stuttering” what do you think of? Many people think that stuttering is when someone repeats a sound. However, there are different types of stuttering, and each person who stutters has a different and unique way of speaking. Stuttering is like an iceberg because there is a small part of it that we can see (or hear), but a big part of stuttering is invisible. People who stutter have thoughts and feelings about stuttering that we cannot see. Because most people who stutter only stutter sometimes, they must decide if and how to let other people know about their stuttering. We will discuss how stuttering can impact kids and adults and what you can do to support people who stutter.

What is Stuttering?

For many people, talking is something that requires little effort. We rarely think about the complicated ways that the brain, jaw, tongue, lips, lungs, and vocal folds work together to produce speech. How might your life be different if it was difficult for you to say your name? For people who stutter, talking is not always easy. In this article, we will discuss what stuttering is and why it is an invisible condition. We will also describe ways to support people who stutter.

Stuttering is a communication disorder that affects the fluency of a person’s speech, which means the ability to smoothly link sounds and words together. No one has perfectly fluent speech. We all produce disfluencies (or breaks in fluent speech) from time to time. For example, it is common to insert words like “um” into speech and to repeat words or phrases on occasion.

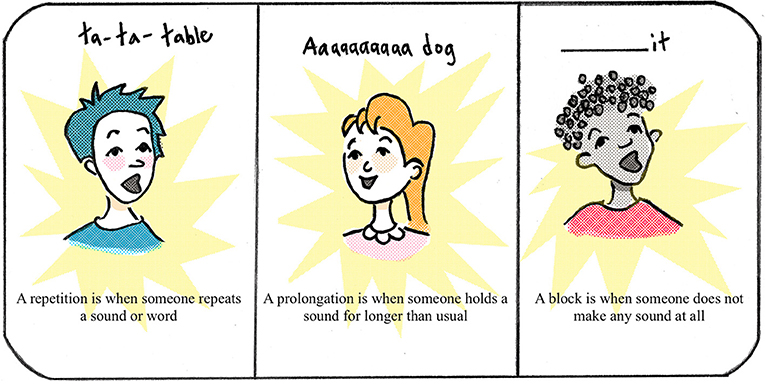

Although we all have times when we are disfluent, we do not all stutter. People who stutter produce certain types of disfluencies that are unique to stuttering, called stuttering-like disfluencies [1]. For example, people who stutter sometimes repeat sounds or get “stuck” in the middle of a sound. Other times they may have difficulty producing any sound at all. Figure 1 shows examples of different stuttering-like disfluencies.

- Figure 1 - Repetitions, prolongations, and blocks are examples of different types of stuttering-like disfluencies.

One reason why stuttering-like disfluencies are unique is because they are associated with a loss of control. If you have ever slipped on ice, then you have probably experienced a similar feeling. When you feel yourself start to slip, it is normal to tense your muscles or brace yourself for the fall. Some people who stutter react to the loss of control associated with stuttering in the same way. They may tense the muscles of the face, neck, or other body parts. This tension is an example of an associated behavior. Associated behaviors are things that people who stutter do when they feel a loss of control during a moment of stuttering. Blinking, looking away, and head movements are examples of other associated behaviors.

Stuttering involves more than the behaviors that we see and hear. It also includes thoughts and feelings about communication [2]. Some people who stutter are afraid to talk because of how others may react to their stuttering. Other people who stutter are not bothered by their stuttering, and some people are proud of the way they talk. When it comes to stuttering, thoughts and feelings are important because they influence communication in everyday life, such as if people who stutter are comfortable enough to raise their hands in class or call their friends on the phone.

We have discussed what stuttering is, but what causes stuttering? Stuttering is a result of wiring differences in the brain. There are many factors that influence whether or not a person stutters [3]. One of the primary contributing factors is genetics. Research has shown that there is not just one gene linked with stuttering, but many genes. Around 60% of people who stutter have a family member who stutters [4]. There are 3 million people who stutter in the United States. That is as many people who live in the entire city of Chicago! Boys are three times more likely to stutter than girls, and most people start stuttering when they are preschool age [5].

In What Ways is Stuttering Invisible?

There are two important reasons why stuttering can be considered an invisible condition. First, stuttering is variable. If something is variable, that means that it changes over time. For example, the weather in the state of Michigan during fall is variable because it can be cool in the morning and scorching hot by lunch time. Similarly, stuttering is variable because most people who stutter only stutter sometimes, and the rest of the time their speech can sound smooth or fluent. For people who stutter, this variability can be challenging. They may not know what their speech will sound like from day to day or even from one conversation to the next!

The variability of stuttering can also be confusing for listeners. Just because people who stutter can speak fluently sometimes does not mean that they can speak fluently all the time. If you have a friend who stutters, you may notice that she does not stutter very much in some situations but stutters a lot in other situations. Although it is completely normal, the variability of stuttering can be hard for kids, teachers, and even parents to understand! Regardless of whether we can see or hear a person’s stuttering, what they have to say is important and worth listening to.

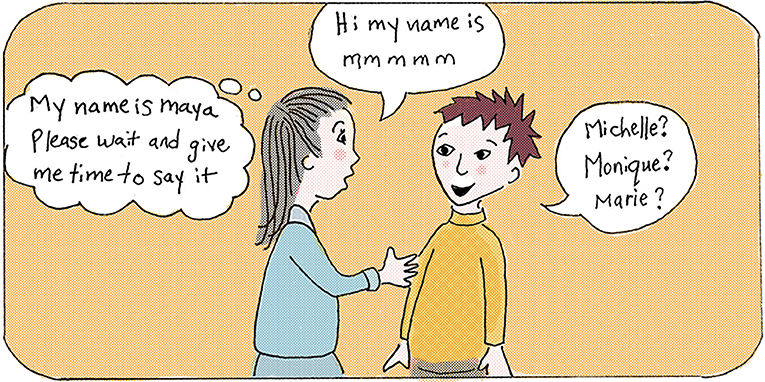

The second reason why stuttering can be considered an invisible condition is because it is concealable, which means that it can be hidden from others [6]. Sadness is another example of something that is concealable. Similar to stuttering, we may sometimes feel sad on the inside but try to hide our sadness from other people on the outside. Sometimes people who stutter get a feeling that they are about to stutter on a word right before they say it. Because they sometimes know when they are about to stutter, they may choose to change that word to hide their stuttering. For example, if a person has a feeling that they will stutter on the word “p-p-p-puppy,” they may choose to say “dog” instead. Some people are skilled at hiding their stuttering, but it may result in them holding back and not saying what they want to say. Sometimes the consequences of concealing stuttering are even bigger, as illustrated in Figure 2.

- Figure 2 - Sometimes people who stutter might order something they do not want to eat because it is easier to say.

- It is important to be patient and give them the time they need to say what they want to say.

What Are Some Challenges That People Who Stutter Encounter?

Because stuttering can be invisible, people who stutter have to make decisions about if and how to let others know about their stuttering. In a survey study, 60% of teenagers who stutter reported that they “rarely” or “never” talk to other people about stuttering [7]. Although some kids prefer not to talk about their stuttering, others prefer to be more open about it. People who stutter can let other people know about their stuttering in different ways. For example, they can say something like, “In case you were wondering, I stutter and that is just the way I talk.” They could also choose to let other people see and hear their disfluency by stuttering openly. It should be up to each person who stutters to decide if, when, and how they want to be open about their stuttering.

One reason why some kids may not talk about their stuttering is because they may have been treated badly for stuttering in the past. Most people who stutter have had to deal with microaggressions related to stuttering. If we break that word down, “micro” means small, and “aggression” refers to hurtful attitudes or behaviors. Thus, a microaggression is when someone says or does something that seems small and harmless but is actually hurtful toward a specific group of people. People who commit microaggressions do not always do so on purpose. For example, when people are not familiar with stuttering, they may think it is best to interrupt and guess what people who stutter are trying to say. This experience can be frustrating for people who stutter because they know exactly what they want to say. They sometimes just have trouble saying it. The illustration in Figure 3 provides an example of a microaggression that could happen in real life.

- Figure 3 - The best thing to do when someone is stuttering is to wait patiently.

- It can be frustrating for people who stutter when others try to guess what they are trying to say.

Interruptions are not the only type of microaggression that people who stutter encounter. People who do not understand stuttering sometimes think it is helpful to give people who stutter advice about stuttering. For example, they may tell them to “slow down.” Although slowing down can be helpful for some people who stutter, it is not something that all people who stutter like to do. Most people who stutter already have at least some knowledge about what does and does not help their communication.

If people who stutter do want or need additional help related to communication, professionals called speech-language pathologists or even other people who stutter have the appropriate expertise or personal experience to provide support. Some people who stutter may go to speech therapy for help with their stuttering or to improve their overall communication. There are lots of different things that people who stutter might work on in therapy. For example, they may learn about ways to stutter with less tension or work on changing negative thoughts and feelings about communication. Right now, there is no “cure” for stuttering. However, over time, people who stutter can learn and practice ways to make talking easier and more enjoyable.

What Are Some Ways to Support People Who Stutter?

You can support your friend or classmate who stutters by being kind, respectful, and patient. Here are a few other examples of how you can be supportive of people who stutter:

- Ask your classmate or friend who stutters about specific ways you can support them. Most kids who stutter probably do not want you to finish their sentences. On a hard speech day, they may be okay with you ordering their school lunch so they can take a break from talking. Sometimes, however, it may be important to them that they order their own lunch. Each situation is different and each person who stutters is different in how they want support.

- Understand that people who stutter are just like everyone else, but they sometimes need a little extra time to say what they want to say. Stuttering is only one part of who they are. Build your friendships with them in the same way you would with any other kid based on common interests like sports, art, videogames, or music.

- Recognize that it is okay to stutter. Kids who stutter may or may not be in speech therapy, and that is okay. Your friend may be comfortable stuttering in front of you or may choose to use speech strategies when talking with you. Support people who stutter in whatever they choose.

Glossary

Stuttering: ↑ A communication disorder or way of speaking that impacts a person’s ability to smoothly link sounds and words together.

Fluency: ↑ The ability to smoothly link words and sounds together in speech.

Disfluencies: ↑ Breaks in fluent speech that are common among all speakers.

Stuttering-like Disfluencies: ↑ Disfluencies that are unique to people who stutter, including repetitions, prolongations, and blocks.

Associated Behaviors: ↑ Things that people who stutter do when they experience the feeling of loss of control while stuttering.

Variable: ↑ When something changes over time.

Concealable: ↑ When something is able to be hidden from others.

Microaggression: ↑ When someone says or does something that seems harmless, but is actually hurtful toward a specific group of people.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jack Gunderson and Josette Tugander for their comments on the initial draft of this manuscript. We also wish to extend gratitude to Anthony Wislar for adding color to the illustrations.

References

[1] ↑ Yairi, E., and Ambrose, N. 1992. A longitudinal study of stuttering in children: a preliminary report. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 35:755–60. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3504.755

[2] ↑ Yaruss, J. S., and Quesal, R. W. 2004. Stuttering and the international classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF): an update. J. Commun. Disord. 37:35–52. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9924(03)00052-2

[3] ↑ Smith, A., and Weber, C. 2017. How stuttering develops: the multifactorial dynamic pathways theory. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 60:2483–505. doi: 10.1044/2017_JSLHR-S-16-0343

[4] ↑ Bloodstein, O., and Bernstein Ratner, N. 2008. A Handbook on Stuttering. New York. NY: Thomson-Delmar.

[5] ↑ Yairi, E., and Ambrose, N. G. 1999. Early childhood stuttering I: persistency and recovery rates. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 42:1097–112.

[6] ↑ Petrunik, M., and Shearing, C. D. 1983. Fragile facades: stuttering and the strategic manipulation of awareness. Soc. Probl. 31:125–38.

[7] ↑ Blood, G. W., Blood, I. M., Tellis, G. M., and Gabel, R. M. 2003. A preliminary study of self-esteem, stigma, and disclosure in adolescents who stutter. J. Fluency Disord. 28:143–59. doi: 10.1016/s0094-730x(03)00010-x