Abstract

More and more research is showing how spending time in nature is good for our health and development. Yet, children living in urban areas (towns and cities) may find it difficult to spend time in nature. Their neighborhoods may have little nearby nature to interact with, or they may not be allowed travel on their own to reach natural spaces. Missing out on spending time in nature means children are becoming more disconnected from the natural world. We wanted to understand if children living in urban areas have access to nature in their neighborhoods. Then, if they do have access to nature, do they prefer to spend time in nature, or in other kinds of spaces? What reasons either prevent or encourage use of natural spaces? Our work revealed some new findings on how children interact with nature and how we can improve our urban areas to support nature connection.

The Human Habitat

We are willing to bet that you live in an urban area, such as a town or a city. Most of the world’s population does, and more and more people are moving into urban areas every year [1].

Urban areas are very different environments from those in which our ancestors lived. Our ancestors made their homes in woodlands, grasslands, wetlands, beaches, and scrubland. Most of us today live in environments dominated by man-made structures, like buildings and roads. While urban areas do contain nature of a kind, this nature is often very different from the “wild” nature we see outside of cities and towns in rural areas. For example, think of parks, gardens, or yards. These spaces are green and can contain many species of plants and animals. But the number of these species and their abundance (that is, their “biodiversity”) is usually lower than that of natural environments like woodlands or beaches.

This shift from living in rural to urban environments means there has been a massive change in our surroundings and how we interact with nature in our daily lives. In our research, we wanted to look at how children growing up in urban areas interacted with the nature around them. We wanted to explore two key theories related to this question, which we will explain below.

A Tale of Two Theories

The first theory is called the biophilia hypothesis. Proposed in the 1980s, it suggests that people have an in-born preference for nature (“bio-”), and an attraction (-“philia”) to natural things or places [2]. The idea is that those areas that were richer in plants and animals were better places for humans to survive and thrive. This theory suggests that our ancestors developed an attraction to natural spaces, where they spent more time and were more likely to settle, and that this attraction remains in modern humans despite our drastic change in habitat.

The second theory is the nature deficit disorder. This theory came from the idea that children today are spending less time out in nature, and as a result are suffering more and more from problems such as difficulty concentrating, high stress levels, and poor physical health [3]. What is more, not spending as much time with nature means that children today are not learning as much about nature, nor establishing a connection to it.

There are interesting questions that come from these two theories. If biophilia is present in children today, and if urban areas contain some places that have more biodiversity than others, then children should be attracted to spend time in these more natural places. By doing this, they maintain their connection to nature and perhaps reduce the possibility of developing nature deficit disorder. However, if biophilia is not present, then nature deficit disorder might become more difficult to prevent.

By exploring how children interact with urban nature, we hoped to better understand whether growing up in urban environments could be harmful to children’s well-being.

Testing the Biophilia Hypothesis

We set out to ask the question, “Are children biophilic?” To do this, we wanted to examine children’s use of the areas around them. If the biophilia hypothesis is true, we would expect children prefer to spend time in biodiverse areas in their neighborhoods. We were interested in where children go when they are with friends or on their own, not with adults. So, we designed a study to find out where children spent the most time outside, and whether they used the more biodiverse habitats in their urban neighborhoods.

To do this study, we first needed to understand the amount of biodiversity contained in different urban areas, how much of the biodiversity was accessible to children, and finally where children decided to spend their time outdoors. We used the five steps described below.

Step 1: Finding out What Nature is Present in Children’s Urban Neighborhoods

Our first step was to define the biodiversity value of different urban habitats. We developed a system for ranking habitats based on the features and numbers of the plants and animals that could be easily seen. Natural habitats, such as woodlands, scored highest; but “formal” greenspaces, such as parks, also scored highly and large, very green gardens also ranked among the highest. “Gray” habitats, such as streets and paved-over areas such as sports courts, usually ranked the lowest.

Step 2: Finding out Where Children are Spending Their Time Outdoors

In the next step, we needed to find out where children were spending their time outdoors. We interviewed nearly 190 children across three cities in New Zealand. The children were aged 9–11 years and lived in a range of very green urban areas to more gray urban areas. We asked children to add a series of dots onto a map of their neighborhood to indicate the amount of time they spent in different areas outdoors.

We then built up a map of that child’s neighborhood. We identified all the areas available to and used by the children and gave each site a score that represented its biodiversity value.

We defined all sites within 500 m of a child’s home as being “available” to the child. This was to get a measure of the potential biodiversity that surrounded each child in the nearby neighborhood.

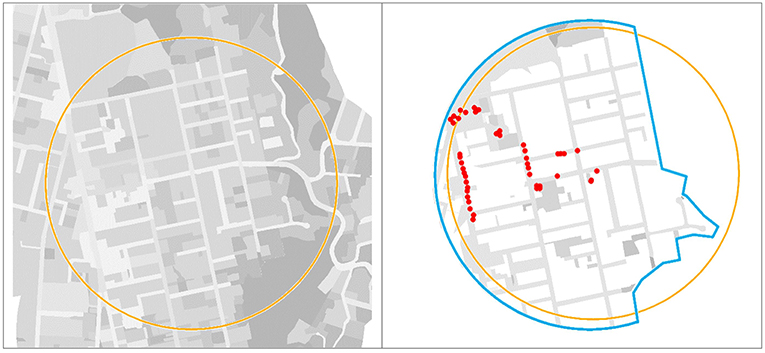

The next step was to identify what areas of each site were “accessible” to each child. This meant removing all areas that were privately owned, such as other people’s gardens, and areas the child said they were not allowed to go to on their own, such as the other side of a busy road. Figure 1 compares the different areas that were available and accessible for one child in the study. By examining what was available and accessible to children, we could see where children were choosing to spend their time outside.

- Figure 1 - Left: One child’s neighborhood range is shown as a 500-m radius circle around his home.

- The different types of area (habitats) were mapped. They are shown in shades of gray, to indicate their biodiversity value: darker grays indicate more biodiverse habitats than light grays. Right: This is the same area, but with the areas the child is not allowed to visit removed, such as private gardens. The blue boundary indicates the areas the child is normally allowed to go on his own. The red dots indicate where the child chose to spend most of his time outdoors.

Results—What are Children’s Habitat Preferences?

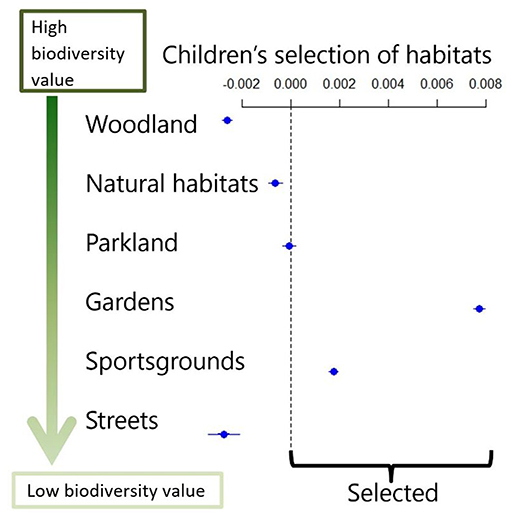

Our study of which areas children preferred to spend time in showed some mixed results. First, children did not show any preference for the most biodiverse area they could visit: woodlands. In fact, children seemed to avoid woodlands; that is, they used woodlands less than would be expected (see text Box 1). Children instead preferred to spend their time in gardens and also on sportsgrounds. Figure 2 shows the preferences of the children in our study to different urban habitats.

Box 1 - Understanding habitat use with Resource Selection Analyses

We used the dots in a technique known as a ‘resource selection analyses’, which is a method developed in wildlife ecology [4]. This method is used to identify the habitat preference of a species so, for instance, selected areas can be protected to help conserve that species. What is important about this technique is it considers the availability of the different habitats. If an animal or child is showing no preference for a particular habitat, then we would expect the proportion of time spent in that habitat to be equal to the proportion of area that habitat makes up of the animal’s range. If an animal were to spend 70% of its time in a habitat that only made up 20% of the total area available for that animal to use, then that habitat is favoured by that animal.

- Figure 2 - Where did children spend their time?

- Based on the scale at the top of the graph, dots with positive values indicate a “preference” for that habitat, and those with negative values indicate avoidance of that habitat. The lines either side of the dot indicate the amount of error around our estimates. Dots with smaller lines mean we can be more confident that our findings are correct. Children’s selection was assessed for six habitats, ranked from most biodiverse at the top to least biodiverse at the bottom using the biodiversity scoring approach outlined in step 1. We can see here that gardens are the most preferred habitats, followed by sportsgrounds. In contrast, woodlands and streets tend to be avoided.

So, are Urban Children Biophilic?

Upon first look, we did not find evidence to support the biophilia hypothesis in the urban children we interviewed—children did not show a greater attraction to the most biodiverse habitats that they could access.

However, we would not jump too quickly to write off the biophilia hypothesis. We first should consider other things that might influence children’s use of the areas around their homes.

First, as you can see in Figure 1, that the habitats children actually access are very different from what is available in their neighborhood. We found that some of the biodiverse habitats close to where children lived could not always be used by them, because of the child’s or their parents’ concerns for safety.

What is the main reason that children use outdoor space? Play, of course! This might explain why habitats that are good to play in, such as sportsgrounds and gardens were most used.

Gardens represent safe places for children to play. Backyards can also be rich in biodiversity. For some children, gardens were the highest biodiversity habitats in their neighborhoods. Perhaps gardens are the best places to combine play, safety, and nature? If so, the biophilia hypothesis is not wrong, it is just one of the reasons for children’s use of habitats.

Encouraging Biophilia in Children

If we encouraged children to spend more time in nature and made biodiverse natural habitats more available, perhaps nature could become a stronger reason for deciding where to spend time outside. Spending more time in nature has been linked to many benefits for children, such as learning new skills, improved physical fitness, and good mental health.

In our research, however, we found that living in urban areas can mean it is difficult to access nearby natural areas. When we think about how our towns and cities are built, we need to also consider how children use and move around in these spaces. Making biodiverse areas more accessible to children could encourage their use and help prevent nature deficit disorder from setting in.

Glossary

Urban Area: ↑ An area dominated by man-made structures rather than greenspace.

Rural Area: ↑ An area away from towns and cities, without many people or buildings.

Abundance: ↑ The number of individuals of plant or animals in a habitat.

Biodiversity: ↑ The richness and abundance of plants and animals in a habitat.

Biophilia: ↑ An in-born love of nature, and an attraction to spending time in natural spaces and biodiversity.

Habitat: ↑ The particular environment of an area, characterized by different plants and animals present within it.

Nature Deficit Disorder: ↑ The idea that children today are spending less time in nature than children from previous generations did. This causes children to develop problems such as difficulty concentrating, high stress, and poor mental and physical health.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑Hand, K. L., Freeman, C., Seddon, P. J., Recio, M. R., Stein, A., and van Heezik, Y. 2016. The importance of urban gardens in supporting children’s biophilia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113:9210–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609588114

References

[1] ↑ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, and Population Division. 2014. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/352). New York, NY: United Nations.

[2] ↑ Wilson, E. O. 1984. Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press.

[3] ↑ Louv, R. 2005. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

[4] ↑ Boyce, M. S., Vernier, P. R., Nielsen, S. E., and Schmiegelow, F. K. 2002. Evaluating resource selection functions. Ecol. Modell. 157:281–300. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3800(02)00200-4