Abstract

The human ear is a fascinating organ that allows us to hear and process all kinds of sounds. It is divided into three sections: the outer, middle, and inner ear. Sometimes, the middle ear can become filled with fluid due to ear infections or structural problems, which makes it difficult to hear sounds. To fix this, doctors called ear, nose, and throat specialists might perform a simple surgery to insert small ear tubes into the eardrum, to drain the fluid behind it. After surgery, the tubes allow children to hear properly, but they must continue to take care of their ears and protect them from germs. The process may seem scary to kids, but it can be very easy as long as they are prepared!

Introduction

The ears are very complex organs that allow us to hear and process sounds. The ear is divided into three sections: the outer, middle, and inner ear. The middle ear is particularly important, as it is sensitive to infection and small changes in fluid and pressure. If a person develops chronic fluid build-up in the middle ear, it may be time to get ear tubes put into their eardrums. These tubes allow the fluid to drain so the person can hear sounds more effectively.

How Sound Travels Through the Ear

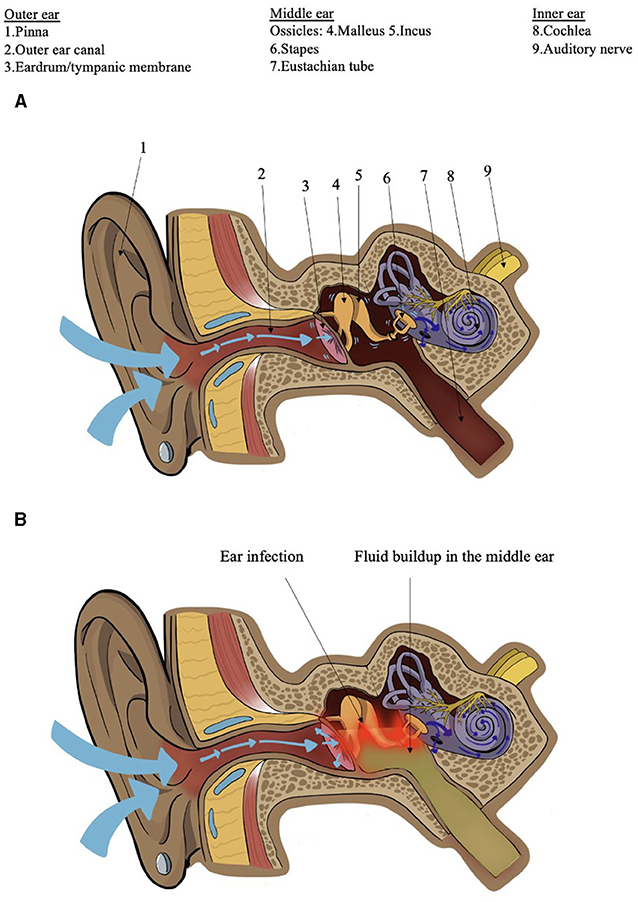

The three parts of the ear work together to gather sound and send it to the brain (Figure 1A) [1]. The outer ear is made up of the pinna and ear canal. The pinna is the part of the ear on the outside of the head. Its curves help capture sound waves and direct them into the ear canal. The ear canal contains hairs and wax, which help prevent foreign objects from entering the ear. Sound waves travel through the ear canal until they hit and vibrate the tympanic membrane (eardrum), a stretched layer of skin that separates the outer and middle ears.

- Figure 1 - (A) Diagram of the ear, showing sound waves (blue arrows) bouncing off the pinna and traveling through the outer ear canal, through the middle ear via the vibration of the ossicles, and through the cochlea of the inner ear to the auditory nerve.

- (B) Fluid build-up in the middle ear causes inflammation of the middle ear and the eardrum (red) and limits their ability to transmit sound into the inner ear.

The middle ear is a space filled with air, and it contains three tiny bones called the malleus (hammer), incus (anvil), and stapes (stirrup), which are connected like a chain. Together, these bones are called the ossicles. When the eardrum vibrates, the ossicles carry the vibration to the inner ear. The middle ear also has a tube connected to the nose, which drains excess fluid and helps to keep the pressure the same on both sides of the eardrum. This tube is called the eustachian tube, and it helps us to hear properly. When the eustachian tube adjusts the pressure, it can create a popping sensation. You may have felt this when flying in an airplane or driving up or down a mountain!

The inner ear contains a snail-shaped structure called the cochlea, filled with fluid that the sound waves travel through. The cochlea has tiny hairs, which change vibrations in the liquid into electrical signals that travel up the auditory nerve to the auditory cortex of the brain, allowing us to process sound.

What Are Ear Tubes and Why Might We Need Them?

When sound gets blocked in the ears, there are several ways to fix it. If there is wax in the outer ear, it can be cleaned out with water. If there is fluid in the middle ear, a pair of ear tubes might be needed.

Ear tubes are very tiny tubes (Figure 2) that doctors use to drain the middle ear when there is too much fluid inside. There are two ways for fluid to build up in the middle ear. The first is otitis media, a middle ear infection caused by bacteria or viruses coming in from the nose or mouth. The germs sit in the fluid of the middle ear, causing cold symptoms or fever, and the ear can become red and painful (Figure 1B). Any child can get an ear infection, but someone who has more than one infection in a few months might need tubes to get the germs out! If the infection is not taken care of, the germs may enter the skull and brain, which is very dangerous.

- Figure 2 - A photograph depicting the actual size of an ear tube compared to a penny for scale.

The second way for fluid to build up is if the eustachian tube stops working. The job of the eustachian tube is to balance the pressure on both sides of the eardrum and drain any fluid out of the middle ear, through the nose. If the eustachian tube is blocked or not shaped right, then the fluid will stick around. This is common in children under five, when the tube is shorter and more horizontal than an adult’s [2]. The child’s ears might not hurt, and they might not feel sick, but their ears might feel full, like they are underwater, making it difficult to hear normal sounds. If this continues for a long time, especially in young children, they can develop issues with speech, language, and learning—so it is important to treat it quickly.

Ear tubes allow the eardrum to work properly again, and to bounce sound waves toward the inner ear. Because they are so tiny, doctors must put the tubes into the ears during surgery. This operation is called a tympanostomy, and it is one of the most common surgeries performed in children, most commonly in those aged 1–5 [2].

If you ever find that you are getting multiple ear infections in a year, if you feel fluid in your ears for 3 months or more, if you need people to speak loudly so you can hear them, or if you always need to turn up the volume on the TV, tell your parents! They can take you to your doctor, who will check your ears. The doctor will use a device called an otoscope to check your eardrums. Normally, eardrums look thin, shiny, and pink. If you have an ear infection or chronic fluid build-up, the eardrum may look bright red, bulging, and dull from the fluid [3]. If this is the case, the doctor may arrange for you to go to the hospital for surgery.

Inserting Ear Tubes, and Taking Care of Them Afterwards

Surgery might sound like a scary thing to a kid! But the more you know, the easier it is to prepare. Every surgery is a team effort, with a surgeon, anesthesiologist, and nurses. The type of surgeon that puts in ear tubes is called an otolaryngologist or ear, nose, and throat doctor. The anesthesiologist puts you to sleep using general anesthesia, wakes you up, and makes sure that you do not feel pain before or after the surgery. The nurse works together with the doctors to keep you safe and comfortable the whole time.

As the patient, it is important to know what the day will be like. First, on the morning of the surgery, you cannot eat any breakfast. This is very important, because you must have an empty stomach to be put to sleep. Second, you will need to wear comfortable clothes, like pajamas, that you can fall asleep in. Third, you will need to bring something from home that makes you happy! Maybe it is a toy, blanket, stuffed animal, or book. The most important thing is for you to feel comfortable.

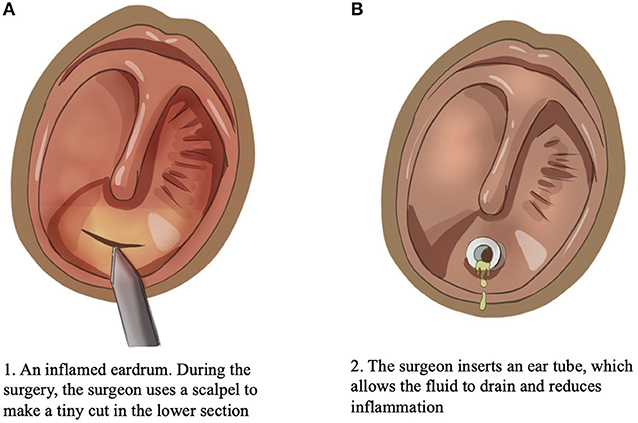

Once you are in the operating room, the anesthesiologist will give you a gas through a plastic mask that quickly puts you to sleep, so you will stay still and not feel any pain. While you are asleep, you will get pain medication through a needle, which stops you from feeling anything, even after you wake up. The surgeon will then reach into your ear, make a small cut in the eardrum, and insert the tube (Figure 3). The entire process only takes 15 min to complete [4]. You will then be moved to a recovery room where you gradually wake up. You may feel drowsy for a few hours after the surgery, but once you wake up and are safe to move around, you can go home. It is normal for your ears to feel itchy or clogged for the first couple weeks. Since the tubes are providing an opening from the outer to the middle ear, it is important to keep your ears dry to prevent bacteria from growing. Make sure you use the antibiotic drops the doctor gives you and follow your doctor’s instructions about bathing and swimming. You may even need to wear ear plugs or a headband for swimming, to protect your ears from bacteria!

- Figure 3 - (A) In a surgery called a tympanostomy, a surgeon uses a small scalpel to make an incision in the lower section of the inflamed eardrum.

- (B) An ear tube is inserted, allowing the fluid in the middle ear to drain and reducing the inflammation.

After surgery, your doctor will set up another appointment soon, to check that the ear tubes are properly in place and that you do not have a blockage or infection [5]. At this appointment you may have a hearing test, which will show how much your hearing has improved.

Ear tubes stay in your ears for 8–15 months, or longer. Usually, the tubes fall out on their own because your eardrum is constantly healing and growing. Eventually, all that will be left is a tiny scar. You may need another pair of tubes at some point, but luckily it is a very simple procedure and does not affect your hearing long-term.

Conclusion

The ears are fascinating organs that allow us to process and respond to sounds. The middle ear is very prone to damage and fluid build-up from infection and blockage of the eustachian tube, and when fluid builds up frequently and affects hearing, it may be time to get ear tubes. Ear tubes are small, simple devices that allow many children with chronic ear infections and hearing loss to lead normal lives. The surgery and aftercare are simple, as long as you are prepared!

Glossary

Tympanic Membrane: ↑ Also called the ear drum; the membrane that separates the outer and inner ear and allows sound to be transmitted between them.

Eustachian Tube: ↑ Tube that connects the middle ear to the nose, which equalizes the pressure on both sides of the ear drum and drains excess fluid and bacteria.

Ear Tubes: ↑ Tubes that are placed in the tympanic membrane to drain excess fluid and prevent hearing loss.

Otitis Media: ↑ Middle ear infection, usually due to bacteria or viruses. Can cause fever, redness, pain, and hearing loss.

Tympanostomy: ↑ Surgery to insert ear tubes. Very common procedure in young children, usually under general anesthesia.

Anesthesiologist: ↑ A doctor who specializes in preventing or relieving pain and putting patients to sleep, during surgery.

Otolaryngologist: ↑ A surgeon who specializes in procedures involving the ears, nose, and throat. They insert ear tubes into the patient’s ear.

General Anesthesia: ↑ A state caused by a combination of gas and pain medication, which causes the patient to stay asleep, unmoving, and unable to feel pain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Szymanski, A., and Geiger, Z. 2022. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Ear. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

[2] ↑ Rosenfeld, R. M., Schwartz, S. R., Pynnonen, M. A., Tunkel, D. E., Hussey, H. M., Fichera, J. S., et al. 2013. Clinical practice guideline: tympanostomy tubes in children. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 149(1_Suppl.):S1–35. doi: 10.1177/0194599813487302

[3] ↑ Ruah, C., Penha, R., Schachern, P., and Paparella, M. 1995. Tympanic membrane and otitis media. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 49:173–80.

[4] ↑ Spaw, M., and Camacho, M. 2022. Tympanostomy Tube. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565858/ (accessed March 13, 2023).

[5] ↑ Isaacson, G., and Rosenfeld, R. M. 1996. Care of the child with tympanostomy tubes. Pediatr Clin North Am. 43:1183–93. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70513-7