Is it important to have friends? Why do we enjoy spending time with them? Do we learn differently around our friends? Neuroscience research is helping us to answer some of these questions by looking at the way our brain allows us to, and benefits from, interacting with other humans. Part of the reason why human brains are so complex is that our interactions with others are so complex; we are social creatures and have been living in groups for thousands of years. Our brain has developed the ability to handle the complexity of the social world that our species (human beings) have created. We organize our interactions into different levels of complexity: we tell apart our closest family members, we can help our neighbors, we belong to a nation, and we recognize ourselves as a part of the large world. But why have humans developed such complex social organizations? Interacting with others has been helpful to us as a species: there is something about cooperating with others that made us more fit to survive through evolution (Figure 1).

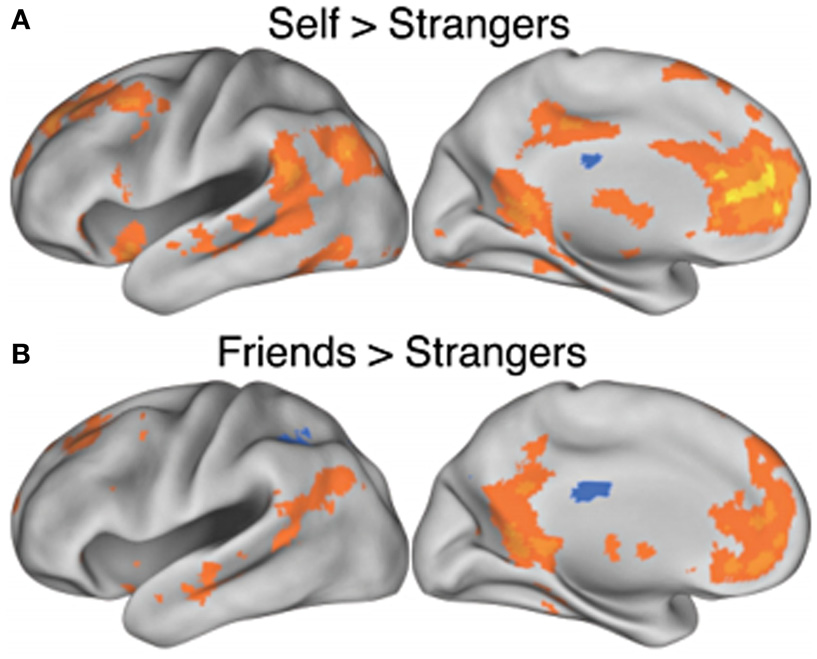

In fact, research shows that human beings who are socially isolated not only report higher rates of depression, which is a state characterized by persistent feelings of very low mood, they also get sick more often and live shorter lives [1]. Many brain functions are involved in allowing us to have healthy human interactions. One such function is empathy. Empathy allows us to understand and respond to the emotional experiences of others. A key part of empathy is “theory of mind,” the ability to understand other’s feelings, beliefs, thoughts, and intentions. Without realizing it, we use this ability every time we interact with our family, friends, classmates, and teachers: in order to have healthy social interactions, we have to understand that they think and feel differently than we do. But, we are not born with this ability. It is not until we are between 4 and 5 years that theory of mind starts developing, and this leads to many changes in our behavior, such as learning new social rules and being able to play more complex games with friends. Figure 2 shows that the brain network activated when thinking of our own mind and the mind of a friend is strikingly similar when compared to the brain activity seen when we try to understand the mind of a stranger. That is, our brain does make a difference in the way it responds to friends versus unknown people.

- Figure 1

- A group of teenagers building their friendship.

- Figure 2 - Brain activity.

- When thinking of one’s own mind and the mind of a friend is very similar in comparison to the activity observed when thinking of a stranger’s mind [2].

Research also suggests that learning in a classroom with teachers and friends is more effective than learning on your own. For example, in a study with American infants who had only been exposed to the English language, three different kinds of teaching were applied to teach kids to distinguish Chinese sounds and words. Some learned with a Chinese teacher in person, others learned by watching the Chinese teacher on a TV screen, and others by only listening to the Chinese teacher. Even though they all taught the same words and for similar periods of time, the first group learned the best and their skills were most like children who grew up speaking Chinese. Apparently, there was something special about the interaction with other humans that made the learning different: perhaps when we interact with other people, there is an extra boost of motivation that makes us learn better [3]. After all, all of us tend to remember things that were taught by our favorite and most engaging teachers. This shows the long-lasting effect of empathy on learning.

Researchers around the world are spending more and more time studying friendship. There is evidence showing that our brain responds more strongly to friends than strangers, even if the stranger has more in common with us. Spending time with friends has been shown to cause more activity in the parts of the brain that makes us feel good – the reward circuits. What is more, having long-lasting valuable social relations, including friendships, and an active social life appears to protect the brain from illnesses later in life such as dementia, the loss of nerve cells in the brain that affects the brains of many older adults.

In summary, the contribution of brain to human social interactions is complex and not yet fully understood. What is clear now is that our brain enjoys making friends and that spending time with them can have very positive effects on learning, health, and life in general.

References

[1] ↑ Cacioppo, J. T., and Hawkley, L. C. 2003. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect. Biol. Med. 46:S39–52. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0063

[2] ↑ Krienen, F. J., Tu, P.-C., and Buckner, R. L. 2010. Clan mentality: evidence that the medial prefrontal cortex responds to close others. J. Neurosci. 30:13906–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2180-10.2010

[3] ↑ Kuhl, P. K., Tsao, F.-M., and Liu, H.-M. 2003. Foreign-language experience in infancy: effects of short-term exposure and social interaction on phonetic learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100:9096–101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1532872100