Abstract

Large land and ocean mammals, like elephants and whales, play essential roles in the environment but are severely threatened by human activities. Images taken from planes can be used to spot these animals from the air. However, these species are difficult to observe because they are rare and move a lot, so unfortunately there are not many images collected from planes that contain these species. Fortunately, however, people share many photos and videos of large animals on social networks because these animals are attractive. These images have been used by researchers to train a computer program to recognize an endangered ocean mammal: the dugong. The program found up to 79% of the dugongs present in images collected by a plane flying around the main island of New Caledonia, which is in the Pacific Ocean. The goal is to use this program to automatically count and map dugongs in New Caledonia.

What is Megafauna?

Large animal species are grouped together under the term megafauna. The word “megafauna” comes from megas in Greek, which means “large” and fauna in Latin, which means “animal life.” Earth’s megafauna includes terrestrial (land) species like elephants and bears, and marine (ocean) species like whales and sharks. Many of these animals are loved by the public, so they are called charismatic species. These species have important roles in the environments where they live. For example, large herds of bison have positive impacts on grasslands, where they feed on weeds [1]. Despite their importance, some species of megafauna are highly threatened [2]. The most important causes of their decline are hunting, elimination of their living environments, pollution, and climate change.

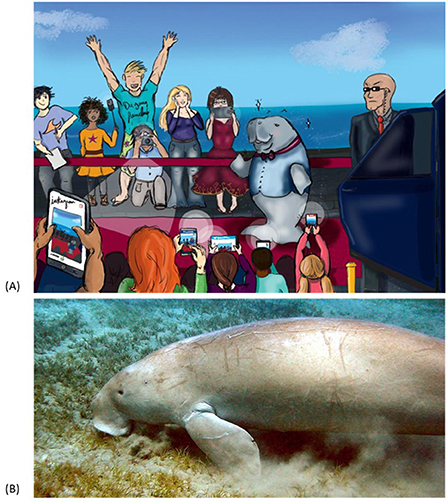

The dugong is one charismatic megafauna species (Figure 1). It is a marine herbivore of up to 3 meters (9.8 feet) in size, and it lives in the warm, sheltered waters near the coasts of the Indian and West Pacific Oceans. Dugong populations are declining, so it is important to study them. However, counting dugongs is a difficult job because it requires a lot of time and money. Scientists use planes and drones to detect them, but it is necessary to travel many kilometers to spot only a few individuals. Fortunately, recent developments in artificial intelligence and social networks can help scientists with this challenge.

- Figure 1 - (A) The dugong, a charismatic ocean species that many people like to photograph.

- (B) Photo of an actual dugong. Photo credit: Mark Goodchild, license CC-BY 2.0.

Artificial Intelligence to the Rescue

In the past, researchers often spent a lot of time watching the videos they recorded in nature. The task of spotting and identifying species on videos is tiring and boring. More recently, researchers started using computer programs that can automatically spot animals on videos.

To detect species in video images, researchers use artificial intelligence (AI). AI consists of a “tiny brain,” which is a rough imitation of the human brain, programmed on a computer. To teach the AI program to recognize animals, the researchers show the program many example images of the species. This step is called training. So, if researchers want AI to do the job of identifying dugongs in videos, they first need to teach the AI program what a dugong looks like, by showing it many images of dugongs. The AI program learns to recognize a dugong like a baby would learn to recognize its mum! The problem is that we have only a few images of dugongs to start with!

How Can Social Networks Help to Train AI Programs?

AI programs need many images to learn from, and social networks are underused sources of images. A social network is a website that allows a group of people to communicate and share information on the internet. Users of social networks publish content such as text messages, images, and videos. To date, the most popular social networks are Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok.

For researchers, social networks are an important and accessible source of information, especially for charismatic species. Because charismatic species are very popular, social network users like to share their pictures and videos. For example, there are numerous videos and photos of dugongs posted on Facebook and Instagram. Researchers can use these videos and photos to enrich their collection of dugong images. This is one of the principles of iEcology, which is the use of information from the internet to help ecology research [3].

An AI Program to Spot Dugongs

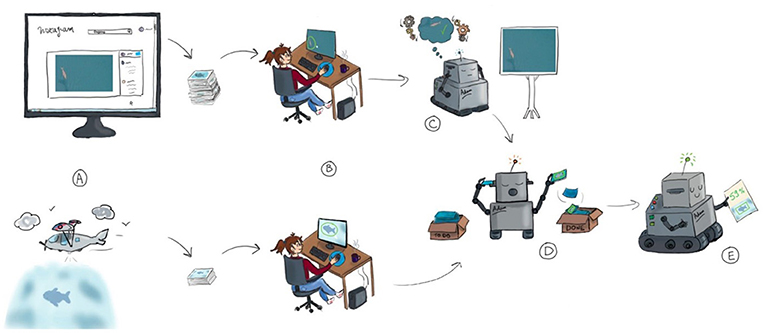

In a new study, researchers trained an AI program to spot dugongs, based on images collected from social networks (Figure 2) [4]. Many images of dugongs were available on social networks, and researchers first drew rectangles around the dugongs to indicate their positions in the images. Next, they gave the marked-up images to the AI program to train it to recognize dugongs.

- Figure 2 - (A) First, researchers used a plane to collect aerial images in New Caledonia.

- At the same time, they looked for aerial images of dugongs on social networks. (B) The researchers put rectangles around the dugongs on both types of images. (C) The social network images were presented to the AI program so that it could learn to recognize dugongs. (D) The program was tested on video images collected in New Caledonia. (E) Researchers calculated the program’s score by comparing the dugongs detected by the program with the dugongs they marked on the images.

The AI program was then tested on images collected from a plane. Researchers attached a camera to the bottom of the plane, to record videos of the water surface in New Caledonia (a French island located in the Pacific Ocean). The aim of the program was to determine whether the images contained dugongs, where the dugongs were, and how many there were. To evaluate the performance of the program, researchers calculated a score for the program, to indicate how well it could identify dugongs. Like a teacher evaluating pupils, the researchers tested whether the program had effectively done its homework! This score was obtained by comparing the dugongs detected by the program to the dugongs marked by the researchers on the social media images. The goal was to create an AI program that could automatically count the number of dugongs in New Caledonia, based only on aerial surveys.

Did the AI Program Work?

When the AI program was tested on images, there were four categories of results (Figure 3):

- Figure 3 - Four categories of results were obtained by the AI program as it tried to recognize dugongs in images: true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), and false negative (FN).

- The program was then given an overall score for how well it could recognize dugongs.

• True positives (TPs): When the program identified a dugong in the image that actually was a real dugong. In these cases, the program was correct.

• False positives (FPs): When the program identified a dugong in the image that was not actually a dugong. In these cases, the program was incorrect. These false positives included corals and rocks that looked a bit like dugongs.

• True negatives (TNs): When the program identified something in the image as not being a dugong when it was not one. In these cases, the program was correct.

• False negatives (FNs): When the program identified something in the image as not being a dugong when it actually was a dugong. In these cases, the program was incorrect. False negatives included dugongs that were too deep below the sea surface to be detected by the program.

The program’s results were considered correct if the numbers of FPs and FNs were very low. The numbers of TPs, FPs, TNs, and FNs allow researchers to better understand the AI program’s mistakes, which can help them find ways to improve the program.

The AI program trained with images of dugongs taken from social networks was only able to detect 59% of the dugongs observed in New Caledonia [4]. But when images from the videos of New Caledonia were added to those from social networks, the program gained 20% accuracy, meaning that it managed to detect 79% of the dugongs—which is great!

Conclusion

The results of the dugong detection program are very encouraging. The current program can still be improved by training it with more images of dugongs. So, take pictures of your favorite wild animals when you can, and share them on social networks—this may be useful for researchers! AI programs and social networks can be used in a similar way to find terrestrial megafauna such as elephants and giraffes. But counting these animals with aerial surveys will only be possible in areas with few trees, such as savannahs, where animals can be seen from the sky.

The final goal of the dugong-detecting AI program is to automatically count and map dugongs around New Caledonia. Knowing where dugongs are and how many there are is critical for monitoring their populations. This information could also improve the protection of dugongs, because new marine reserves could be designed in areas where dugongs are numerous and where they spend a lot of time. In the future, the researchers plan to train an AI program to recognize other large marine animals like sharks, rays, and sea turtles. This will make it possible to count several species at the same time, and even to study how they interact with each other! Using such a program could help to protect multiple ocean species, which could help to keep the Earth’s ocean ecosystems healthy.

Funding

This project received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska- Curie grant agreement No 845178 (‘MEGAFAUNA’).

Glossary

Megafauna: ↑ large animals found on earth like elephants or in the ocean like whales.

Charismatic Species: ↑ Species that attract people’s attention often due to their large size. They include elephants, bears, whales, dolphins, and sharks, which are very popular among the public.

Artificial Intelligence: ↑ Technology in which a computer program like a “tiny brain” learns to make a decision (such as recognizing dugongs in images) based on examples provided to it.

IEcology: ↑ The use of information found on the internet to help ecology research. It includes photos, videos, and locations of species observations, often collected by people who like nature.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑Mannocci, L., Villon, S., Chaumont, M., Guellati, N., Mouquet, N., Iovan, C., et al. 2021. Leveraging social media and deep learning to detect rare megafauna in video surveys. Conservat. Biol. 1:13798. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13798

References

[1] ↑ Geremia, C., Merkle, J. A., Eacker, D. R., Wallen, R. L., White, P. J., Hebblewhite, M., et al. 2019. Migrating bison engineer the green wave. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116:25707–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913783116

[2] ↑ Ripple, W. J., Wolf, C., Newsome, T. M., Betts, M. G., Ceballos, G., Courchamp, F., et al. 2019. Are we eating the world’s megafauna to extinction? Conservat. Lett. 12:e12627. doi: 10.1111/conl.12627

[3] ↑ Jarić, I., Correia, R. A., Brook B. W., Buettel J. C., Courchamp F., Di Minin, E., et al. 2020. IEcology: harnessing large online Ressources to generate ecological insights. Trends Ecol. Evolut. 35:630–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2020.03.003

[4] ↑ Mannocci, L., Villon, S., Chaumont, M., Guellati, N., Mouquet, N., Iovan, C., et al. 2021. Leveraging social media and deep learning to detect rare megafauna in video surveys. Conservat. Biol. 1:13798. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13798