Abstract

Vegetables, exercise, and friends are good for you. Whereas, you already know about the beneficial health effects of the first and second, we want to show you the importance of the latter. Have you ever spent time with friends and felt powerful, safe and indestructible in your group? That is because you share a social identity with them and this social identity influences your mental and physical health. Besides your friends, you have other group memberships—for example, your family or your classmates. These groups make you feel socially integrated and they are a great source of social support in stressful situations. In this article, we introduce the Social Identity Approach—a popular psychological theory, which explains how your feeling of belonging develops and why it is important to identify with a group of other people. Furthermore, we show how social identity can be manipulated and changed in the long term.

Christy wants to improve her health. She already knows that smoking is bad for her and that doing regular exercise is good. But, like most people (and even many doctors), Christy does not know that social relationships are just as important. For example, people who feel alone are more likely to develop mental or physical illness [1]. Research has shown that being a member of multiple social groups is good for your health. You have social groups at home (your family), in school (your classmates), and in the community (your neighbors). Your social groups define your identity and are a source of social support. Social support involves helping people out when they need it.

What is a Social Identity?

Every person has a personal identity and a social identity. Your personal identity is what defines you as unique. It distinguishes you from other children. The basis of your social identity are your social groups. For example, Christy loves to play football and often plays with other children. These children are as excited about football as Christy, and they form a group together. In psychology, we would say that Christy shares a social identity with the other children in her football group. Her football group becomes part of her own social identity.

Surprisingly, you do not even have to talk to other people to share a social identity with them. Christy is walking down the street when she suddenly notices another person wearing a shirt of her favorite football team. Christy will feel more connected to that person than to someone who is wearing the shirt of a different team. Researchers have used similar situations in experiments to change the social identity of their participants. For example, they ask participants to wear same-colored t-shirts (resembling school uniforms or jerseys in sports), and ask them to think of similarities between themselves and the other participants. This allows researchers to see how people act when they share (or do not share) a social identity with each other. These kind of studies help us to understand how social identity affects our behavior.

Theories That Explain Social Identity

Scientists use theories to explain the things that they observe. Theories are useful because, even though there might occasionally be exceptions to them, they help us to understand complicated phenomena, like people’s behavior. In the scientific study of social identity, there are two important theories: social identity theory and self-categorization theory [2]. Social identity theory states that your social identities define you as a person. Self-categorization theory says that which of your social identities is active depends on the situation. At a football match, Christy defines herself as a member of her team. At school, she defines herself as a member of her class or school. In these social situations, Christy’s personal identity is less important than her social identity for defining who she is as a person, and her social identities will have a stronger influence on her actions. In class, Christy will behave more quietly than she will on the football field. Self-categorization theory helps us to understand why people behave quite differently in different places.

Social Support is Good, but Social Identity is Even Better

People receive many benefits from their social groups. Social support is only one of them. Christy experienced this herself: she noticed that she can deal with problems more easily when she receives help from her friends. This is beneficial for her health, because she experiences less stress. Benefits from group memberships are mutual. Within Christy’s football group, the children can both give and receive help. For example, if Christy knows how to perform a ball trick she might explain it to the other group members. As a result, all group members feel that they can achieve much more than they could alone. In psychology, we have found that people who experience such advantages from their social groups are healthier and experience less stress [3].

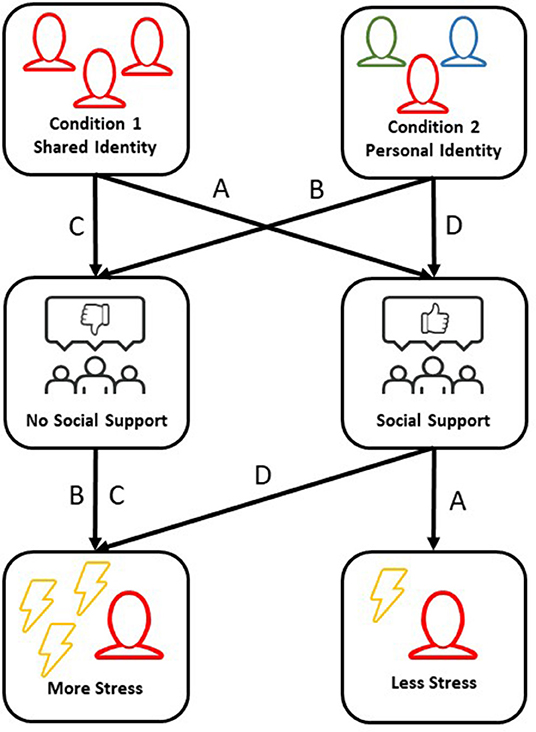

However, it is not the support of just anyone that can have a positive effect on your health. The health benefits of social support depend on your social identity [4]. This is something researchers have confirmed in experiments. In these, participants were asked to perform a speech in front of two strangers (who were actually members of the research team). The participants had only limited time to prepare—very stressful! Half of the participants were told that the two strangers were part of their own social group, meaning the participants thought the strangers shared their social identity. The other half of the participants were told that the strangers were part of a different social group, so participants did not feel a sense of shared social identity with those strangers.

The strangers in both conditions—those with whom the participants believed they shared a social identity and those with whom they did not, either acted in a supportive way or in an unsupportive way. To act supportively, the strangers smiled and nodded now and then during the speech. This gave the participants the feeling that they were doing well. To act unsupportively, the strangers frowned and shook their heads, which made the participants feel insecure.

Before, during and after the speeches, the researchers took saliva samples from the participants and measured the amount of a stress hormone called cortisol in these samples. This allowed the researchers to assess the amount of stress that the participants felt. In the first condition, when the participants and the strangers shared a social identity, the participants were less stressed. As a result, there was a reduced amount of cortisol in their saliva samples. In the second condition, when participants did not share their social identity with the two strangers, the cortisol in their saliva was higher than in the first condition. This showed the researchers that sharing a social identity with the strangers could help to reduce the stress of the participants. But they found another surprising result: in the second condition, the cortisol levels of the speakers in response to supportive and unsupportive did not differ—the way the strangers acted in response to the participant’s speech did not matter (Figure 1). What do these results tell us? They tell us that social support is only beneficial for your health when you receive it from people in your own social groups—people with whom you share a social identity [4].

- Figure 1 - Experiment to test, when the interplay of social identity and social support reduces stress.

- (A) In Condition 1, in which the participant and the two strangers shared social identity, the social support of the strangers reduced the stress of the speaker. (C) When the two strangers acted unsupportively, the stress response was higher. (D) In Condition 2, in which the participant and the two strangers did not share social identity, the social support of the two strangers did not reduce the stress level of the participant. (B,D) It did not make a difference if the two strangers who did not share social identity acted supportively or not. This tells us that social support is only efficient in reducing stress if you are supported by people, with whom you share a social identity.

How Can Someone Develop a Shared Social Identity?

There are several ways to influence your social identity. Researchers have developed a program called Groups4Health, which helps people to feel more socially connected and supported [5]. In the Groups4Health-program, people first learn what social groups are and why they are important for their health. Later, participants create their own social identity map: on a large piece of paper, they write down their own social groups. From there, participants can identify advantages and problems within their social networks. Finally, they can detect which groups are missing in their lives and think about how they can find or build new groups. You do not have to feel lonely to benefit from the Groups4Health-program. Everyone can analyze their social network structure. Ask yourself the following questions: How many social groups do I have? Are my groups compatible with each other? Is there a new group that I would like to join? What is stopping me?

While drawing her social identity map, Christy notices that she has two sport groups: her football group and her swimming group. She realizes that she always has to split herself between these two groups, which is stressful for her. For her birthday, Christy plans to take both groups to a movie. They all have a great time and the children start to form a movie group. Now, Christy no longer needs to split herself between the two groups and always has someone to go to the movies with. Christy now knows that being part of several social groups is not only fun, but also good for her health. Her goal is that her social groups reflect her identity. Therefore, she wants to build positive and lasting social relationships in her life. To avoid stress, it is important to her that her social groups are compatible with each other. Just like Christy, everybody should know about the importance of social groups. This way, every person can successfully use their social networks to their advantage.

Glossary

Mental and Physical Illness: ↑ Mental illness can affect your emotions, thinking, or behavior. Physical illness, like pain in your body or a flu, can sometimes lead to mental illness.

Social Support: ↑ Giving and receiving help from people in your social groups.

Personal Identity: ↑ What distinguishes you from your friends. This might be your taste in music, your hair color, or the school you are going to.

Social Identity: ↑ What you have in common with your friends. Think about the similarities between you and your social groups. Why are you spending time together?

Theory: ↑ A theory explains a broad range of phenomena using only a few assumptions. These general assumptions help us to understand how a specific phenomenon works.

Social Identity Theory: ↑ Your social group memberships shape your social identity and define you as a person.

Self-categorization Theory: ↑ Which of your social identities is active depends on the situation you are in. That is the reason, why you behave differently in different situations.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., and Layton, J. B. 2010. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

[2] ↑ Haslam, S. A. 2001. Psychology in Organizations: The Social Identity Approach. London: Sage.

[3] ↑ Junker, N. M., van Dick, R., Avanzi, L., Häusser, J. A., and Mojzisch, A. 2019. Exploring the mechanisms underlying the social identity-ill-health link: longitudinal and experimental evidence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 58:991–1007. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12308

[4] ↑ Frisch, J. U., Häusser, J. A., van Dick, R., and Mojzisch, A. 2014. Making support work: the interplay between social support and social identity. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 55:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2014.06.009

[5] ↑ Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., Dingle, G., and Xue-Ling Chang, M. 2016. Groups 4 Health: evidence that a social-identity intervention that builds and strengthens social group membership improves mental health. J. Affect. Disord. 194:188–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.010