Abstract

Zombies are real and they can be found around us, in crabs! If you think being mind-controlled by an almost invisible parasite hiding within is terrible, consider infected crabs. Both males and females must help the invading parasite lay eggs and produce babies! We studied edible mud crabs and found that some of them are infected with parasites called rhizocephalans. We noticed that the infected crabs had a weird, egg-like organ underneath their abdomens, and that their overall body sizes were smaller than uninfected crabs. Infected male crabs were turned into females and had female-like wide, dark abdomens. The infected crabs take care of the parasite’s eggs as if they were their own! It is our hope that, 1 day, we will be able to uncover the details of how rhizocephalans turn crabs into zombies.

How It All Began

If you think zombies are just in the movies and in stories our parents told us to keep us at home at night, think again. Although there are no human zombies, zombie crabs and shrimps are roaming freely in the animal kingdom, and the mastermind behind the attack is a tiny parasite.

The group of parasites capable of transforming crabs and shrimps into the walking dead of the sea are also distant relatives of those animals—crabs, shrimps, and the zombie parasites are all Crustacea. Crustaceans have no internal bone structures, but instead possess a strong outer shell to protect them. They need to make a new outer shell to grow, which is a process called molting. However, unlike other crustaceans, these zombie masterminds are part of a special group due to their unique characteristics and lifestyle. The group is called Rhizocephala, and members of this group are called rhizocephalans or rhizocephalan parasites.

Rhizocephalan parasites are very small in size (<300 μm)—about 10 times smaller than a grain of rice [1]. Also, their adult forms are extremely simplified. They have no hands or legs and no internal organs except for reproductive organs, some muscle tissue and a simple nervous system. How can these simple, tiny creatures invade and take over organisms as big and complex as crabs and shrimps?

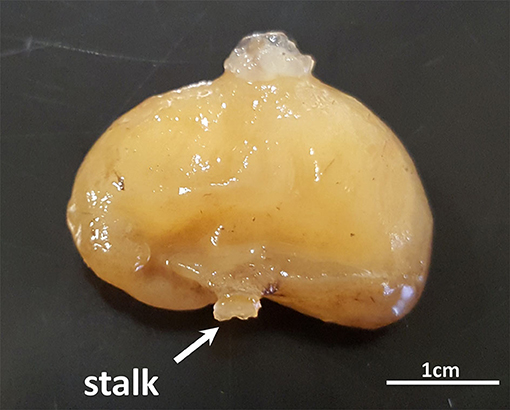

First, for the invasion to be successful, the female parasite needs to find an organism to live in. This animal is called the host, and in this case, it is usually a crab. Once a potential host is found, the parasite will attach itself to the host’s soft tissues, normally at the gills since other parts of the crab’s body are protected by the hard outer shell. After landing safely on the host’s soft tissues, the parasite injects tiny pieces of its own tissues into the host’s body [2]. These parasitic tissues flow within the host’s blood until they locate and attach to part of the host’s digestive system. From there, the parasite grows roots, very similar to the roots of trees, and uses the roots to absorb nutrients from the host. After growing within the host’s body for some time, the female parasite wants to produce babies, but how can it meet its partner, when it is inside the host? So, to mate, the female parasite grows her reproductive organ, called the externa (Figure 1), on the outside of the host’s body. When a male parasite sees the externa sticking out of the host’s body, it enters the externa to fertilize the female parasite’s eggs, and voilà—thousands and thousands of baby parasites are released into the open water, looking for more hosts to turn into zombies [3]!

- Figure 1 - The externa of a rhizocephalan parasite.

- The externa connects to the abdomen of the crab via its stalk.

What Does the Rhizocephalan Parasite Do to Crabs?

We stumbled upon this fascinating discovery while we were collecting mud crabs for other studies. These mud crabs, also known as mangrove crabs, are found in the mangrove forests and river mouths of the Indo-West Pacific region, ranging from India, China, Japan, and Southeast Asia to Australia and Papua New Guinea [4]. They are often collected by fishermen and sold to markets and restaurants, because they are delicious!

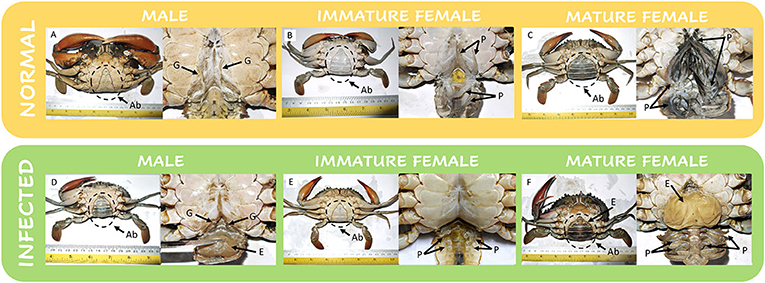

The first thing that caught our attention was the presence of externa under the abdomen of mud crabs, the place where mud crab eggs are usually found. To understand the effects of these parasites on mud crabs, we compared several body measurements between infected and healthy crabs. Surprisingly, we found that all infected male crabs were transformed into females and had female-like characteristics, such as a wide, darkened abdomen and a smaller body size (Figure 2). This body transformation is necessary because male crabs also get infected with the parasite and it affects them the same way it affects female crabs—the parasite’s externa emerges from the bodies of male hosts as well, and both male and female crabs take care of the externa as they would their own eggs!

- Figure 2 - View of the undersides of normal and infected mud crabs.

- (A) Normal male with triangular-shaped abdomen and gonopods of normal length; (B) Normal immature female with slightly globular-shaped abdomen and long pleopods; (C) Normal mature female with globular-shaped, darkened abdomen and long pleopods; (D) Infected male with globular-shaped, darkened abdomen, shortened gonopods, and the presence of externa; (E) Infected immature female with normal immature-like abdomen but shortened pleopods; (F) Infected mature female with normal mature-like abdomen, shortened pleopods, and the presence of externa. G, gonopod; P, pleopods; Ab, abdomen; YS, yellow sack (externa).

Also, both the male and female reproductive organs are shortened drastically in infected crabs. The male reproductive organs are called gonopods, and they consist of two pairs of long structures used to transfer sperm to the female during the mating process. Female reproductive organs are called pleopods, and they consist of four pairs of structures that are important for egg attachment (Figure 2). Shortening of the reproductive organs means that infected male crabs are unable to mate with females, and infected female crabs are unable to attach eggs to their pleopods for normal egg development, even if they can mate with normal males and produce eggs!

In addition to changing the host’s outer appearance, rhizocephalan parasites also control the behavior of their hosts. Infected male crabs with externa will display behavior patterns usually only found in females with eggs on their abdomens, such as constant cleaning of the externa and abdomen, as if they were tending to their own eggs. Imagine that, after being infected with a parasite, you are pregnant with alien babies and, worst of all, being unaware, you take care of them as if they were your own!

At this point, we are still not sure if crabs infected with rhizocephalan parasites are dangerous for humans to eat. It should not be a problem if the crabs are thoroughly cooked before they are eaten. Also, these parasites are very choosy when it comes to selecting their potential hosts. They are only known to infect other crustaceans, not humans.

What Should We Do Next?

It is really amazing how such a tiny organism, with almost no organs or rigid structures, can take control of another organism and cause such tremendous effects. At this time, there is still no treatment for crabs infected with rhizocephalan parasites. Also, we still do not understand how rhizocephalan parasites cause these effects. We hope that, by telling this story, more people—especially kids—will pay attention to the organisms around them in nature, including small crabs. We also want you to be aware of this bizarre rhizocephalan phenomenon, and to help us look for other cases of this parasite. If you live where edible crabs are found, you can look for the presence of a weird yellow sac under a crab’s abdomen. Maybe you can help us solve the mystery of rhizocephalan parasitism someday!

Glossary

Crustacea: ↑ A large group of mostly aquatic organisms with exoskeletons (shells). Their segmented bodies are divided into head, thorax (body), and abdomen. They grow by a process of shedding their shells, called molting. Some example of crustaceans are crabs, lobsters, shrimps, and prawns.

Molting: ↑ The process of shedding an old outer shell and replacing it with a new, often larger one. This process occurs in all crustaceans.

Host: ↑ An organism that is invaded by a parasite.

Externa: ↑ The female reproductive organ of the rhizocephalan parasite. It protrudes from the host’s body underneath the abdomen.

Gonopod: ↑ Male reproductive organs in crabs that transfer sperm into the female during mating.

Pleopod: ↑ Female reproductive organs in crabs that allow egg attachment and ensure normal egg development in crabs.

Parasitism: ↑ The relationship between two organisms, where one (the parasite) lives on or in the other (the host), causing it harm.

Author Contributions

KW and HF drafted the initial framework for the article, finalized the revision, and contributed to the finding of, and research on, the parasite and infected crabs discussed in this article. KW wrote the first draft. HF revised upon the first draft and edited the figures. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑Waiho, K., Fazhan, H., Glenner, H., and Ikhwanuddin, M. 2017. Infestation of parasitic rhizocephalan barnacles Sacculina beauforti (Cirripedia, Rhizocephala) in edible mud crab, Scylla olivacea. PeerJ 5:e3419. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3419

References

[1] ↑ Kobayashi, M., Wong, Y. M., Oguro-Okano, M., Dreyers, N., Høeg, J. T., Yoshida, R., et al. 2018. Identification, characterization, and larval biology of a rhizocephalan barnacle, Sacculina yatsui Boschma, 1936, from northwestern Japan (Cirripedia: Sacculinidae). J. Crust. Biol. 38:329–40. doi: 10.1093/jcbiol/ruy020

[2] ↑ Glenner, H., Høeg, J. T., O’Brien, J. J., and Sherman, T. D. 2000. Invasive vermigon stage in the parasitic barnacles Loxothylacus texanus and L. panopaei (Sacculinidae): closing of the rhizocephalan life-cycle. Mar. Biol. 136:249–57. doi: 10.1007/s002270050683

[3] ↑ Nagler, C., Hörnig, M. K., Haug, J. T., Noever, C., Høeg, J. T., and Glenner, H. 2017. The bigger, the better? Volume measurements of parasites and hosts: parasitic barnacles (Cirripedis, Rhizocephala) and their decapod hosts. PLoS ONE 12:e0179958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179958

[4] ↑ Fazhan, H., Waiho, K., Darin Azri, M. F., Al-Hafiz, I., Wan Norfaizza, W. I., Megat, F. H., et al. 2017. Sympatric occurrence and population dynamics of Scylla spp. in equatorial climate: effects of rainfall, temperature and lunar phase. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 198:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2017.09.022