My son and I have a pet orangutan named Kevin. He talks to us almost every day and usually asks for a banana. All right, he's not a pet, he's a large hairy puppet, and I make him talk using the trick of ventriloquism (see Figure 1). But it is pretty fun anyway. When the puppet moves his mouth, a squeaky voice seems to come out of him, not me.

How does ventriloquism work? Regardless of what you may have heard, people cannot really “throw” their voices to make words come from a different place. Instead, the trick depends on a combination of two different illusions based on two different systems in the brain. When both illusions work together, something happens almost like a magic, and the puppet seems to come to life.

The first illusion is called “visual capture” and it works as given below. If something nearby makes a sound, you can pretty much tell where the sound comes from. But if you see something else move at exactly the same time, you might get the impression that the sound actually comes from the moving object. If a bird chirps in a bush, and you see a door open at the same time, you might think that the chirp came from the door and that the hinges are rusty. The sound is “captured” by the visual movement.

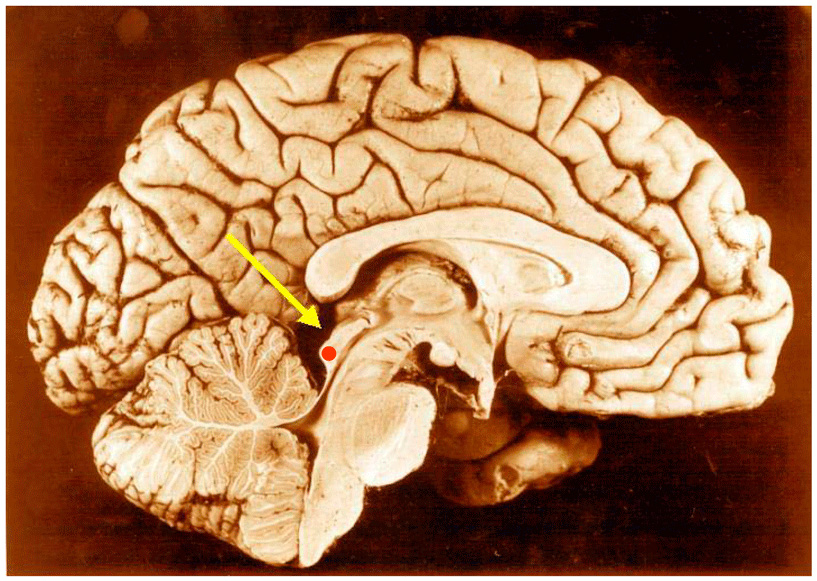

Nobody is certain of how a visual capture works, but neuroscientists have a general idea. Sound enters the ear and is turned into signals within the brain cells. Those cells are called neurons. The signals related to sound are processed in a large set of areas deep inside the brain. About 10 of these processing stations are hooked together, working out basics of the sound such as where it came from. For example, an area in the brain is called the inferior colliculus; “inferior” does not mean it is not good – it means that it is just beneath something else called the superior colliculus (see Figure 2), and “colliculus” means “bump” in Latin. The inferior colliculus has a map in it: a map of the space around a person's body. When you hear a sound from shoulder height and just to the left, the neurons in a specific spot in that map give a surge of activity. This map is a part of the way in which the brain sorts out where specific sounds come from. But amazingly, the inferior colliculus also mixes in information from the eyes [1]. Vision has a way of messing with how the inferior colliculus works. The visual capture illusion may depend on this mixing of signals, although the exact way it happens is not known. Somehow, the brain uses sight to help get a fix on where a sound comes from.

- Figure 1

- Author on the left, dummy on the right.

- Figure 2

- The inferior colliculus (red dot) in a human brain (not my own) which has been cut down in the middle to show some of the sub-cortical areas.

The visual capture illusion goes a long way to explain ventriloquism. When Kevin, the orangutan, talks, the words come from my mouth. But I keep my lips very still, while Kevin moves his big flappy mouth. The result is visual capture. The words appear to be coming from him.

But the visual capture illusion does not explain all of ventriloquism. In fact, it leaves out the most important part! Think about this: suppose you are watching a YouTube video of a person and that person is looking into the camera while talking. You hear a sound coming from a speaker and you see the person's lips moving, and presto, it seems like the sound is coming from the person's mouth. This is visual capture illusion. But nobody is delighted or amazed to see someone talk on YouTube. The visual capture illusion alone is so common that it is no big deal, and most people don't even notice it. Ventriloquism does not work unless there is a social illusion as well.

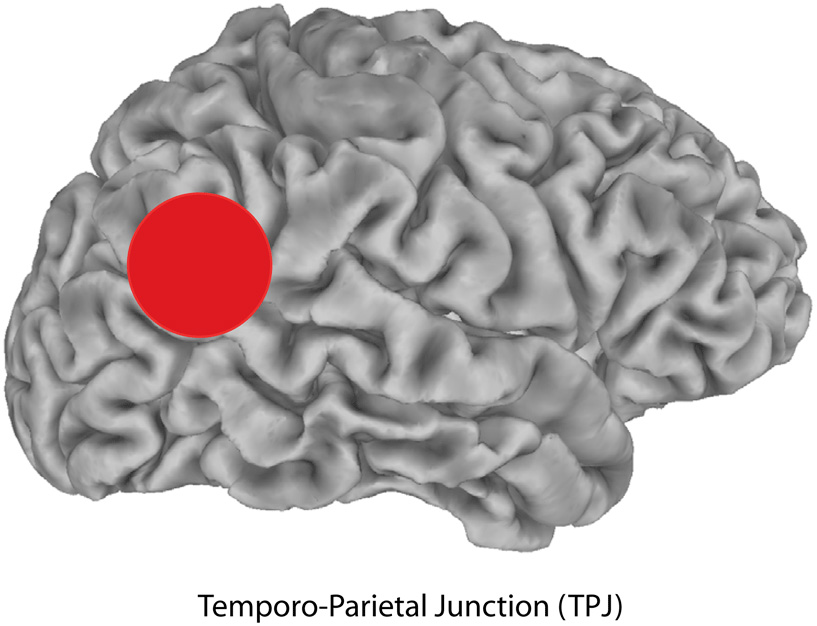

We, humans, evolved to become very socially intelligent. We are good at understanding what other people are thinking and feeling. There are special areas of the brain that do this [2]. Two of them are pretty much just above the ears and about an inch in, on each side of the brain. They are called the “temporoparietal junction”, or TPJ, because it is at the border between a part of the brain called the temporal lobe and another called the parietal lobe (see Figure 3). These two TPJs work together with other areas of the brain and construct a notion of what might be going on in someone's mind. If all the social cues are right, we do more than we see and hear a person, and we also get an idea of the thoughts, feelings, and awareness of that person. We have an impression of consciousness in other person, courtesy of the special social machinery in the human brain.

- Figure 3

- The temporoparietal junction in the cerebral cortex of the human brain (a scan of my own brain).

Ventriloquism can only work when the social illusion kicks in. If Kevin moves his head just right, looking here and there, if his voice sounds particular to him and different from mine, and if he comments on his surroundings, then, he starts to seem alive. He seems to have thoughts and feelings of his own. A great deal of the fun comes from the fact that, while you get the vivid impression that he's conscious, you know that his head is really full of cotton and fingers. When the visual capture illusion and the social illusion come together perfectly, that's when the magic happens.

References

[1] ↑ Groh, J. M., Trause, A. S., Underhill, A. M., Clark, K. R., and Inati, S. 2001. Eye position influences auditory responses in primate inferior colliculus. Neuron 29:509–518. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00222-7

[2] ↑ Graziano, M. S. A. 2013. Consciousness and the Social Brain. New York: Oxford University Press.